Title Page And Preface

“Institutes Of The Christian Religion”, John Calvin. Translated From Latin Into English, By Henry Beveridge, Esq. 1845.

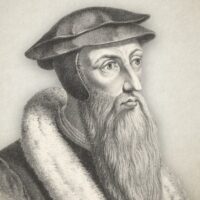

“Calvinism” is a label used to identify a set of teachings drawn up by the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC) in the year 1619. The teachings were in response to those of a Dutch Theologian named Jacobus Arminius. They are nicknamed Calvinism, because they reflect the doctrines set forth by a French Theologian named John Calvin. In 1536, at the age of twenty-seven, Calvin published a doctrinal body of divinity entitled “Institutes Of The Christian Religion”. The Five Points of Calvinism are based upon the teachings of this work.

So much is said about the Five Points of Calvinism, but few have actually read Calvin’s body of divinity. I am therefore pleased to upload this work to the online resources of the AHB, with the hope that those who frequent the homepage will be prompted to read it. To provide a brief overview of the time in which Calvin wrote his book, I copy below the second chapter from John Hazelton’s book, “Hold Fast”.

Jared Smith

——————————————

The River Swift, And Church, Lutterworth

“The sword of the Spirit, which is the Word of God.”—Ephesians 6:17

The peaceful little Leicestershire town of Lutterworth, situated in the midst of beautiful pasture lands, has no more prominent object than its noble Church, the tower of which is visible for miles round. To it many travelers wend their way that they may look upon a place which will ever be association with John Wycliff, who in the fourteenth century was so eminent a patriot and above all so great a spiritual benefactor to his country by his translation of the Bible into the English tongue, multiplying the copies with the aid of transcribers, and by his “poor priests” in their russet gowns recommending it to the perusal of their hearers. His spare, emaciated form, weakened by study, hardly promised a Reformer who could stand before the rising storm, but within this frail body was an immense energy and an immovable conviction, and the personal charm which ever accompanies real greatness drew many around him. He was wondrously strengthened for the work given him to do, and in his well-nigh 300 treatises we have, from the point of language alone, a proof that he is the founder of our later English prose. At Oxford and elsewhere before assemblies of malignant foes he boldly testified, and died at last in peace in 1384, a few hours after administering the Lord’s Supper to the people of his charge. The distinguishing tenet of Wycliff was undoubtedly the election of grace. He calls the Church an assembly of predestinated persons. In his study of the Word he dug down till he came to the first foundations—to those even which the hands of prophets and apostles had laid. He taught that man was fallen through Adam’s transgression; that he was utterly unable to do the will of God or to merit Divine favour or forgiveness by his own power. He taught the eternal Godhead of Christ; His substitution in the room of the guilty; His work of obedience; and free justification by faith in the sacrifice upon the Cross. Morning Star of the Reformation! By the grace of God, sowing by his writings seed which sprang up in the hearts of John Huss and Jerome of Prague and in hundreds of his own countrymen, scornfully nicknamed Lollards—idle babblers—but in the Lord’s remembrance book set down as His own jewels.

The two eminent men just named, with the Bohemian Brethren and John Wessel and John of Wesalia, occupy the century terminating with the appearance of Martin Luther. All alike found in the Word of God their light and life and food; each one bore a clear witness to God’s electing love, and whatever minor differences existed they were one in this. Why was it that all spiritual men who opposed Rome and preached to the people that sat in darkness were on in proclaiming God’s free and sovereign grace? Because Pelagianism, now called Arminianism, is of the very essence of popery; a finished salvation, it knowns nothing of and rejects the necessity of the irresistible and invincible operations of the Holy Spirit.

Martin Luther

The facts of Martin Luther’s life are so well known that reference need only be made here to his sermons and writings as a presentment of the everlasting Gospel. Just as Huss first preached with power in Bethlehem Chapel, Prague, founded by a citizen who laid great stress upon the preaching of the Word of God in the mother tongue of the people, and who named his chapel “The House of Bread”, because there he meant that the people should be fed upon the Bread of Life, so Luther opened his public ministry in one of the humblest churches in Germany—and old wooden building in the center of the square at Wittenberg. His animated face, his kindling eye, his thrilling tones, above all, the majesty of the truths he announced, evidenced, to use the language of Melanchthon, that “his words had their birthplace, not on his lips but in his soul.” He did not come forth as a theologian fully furnished with a scheme of doctrines, but advanced slowly as himself a learner, his conscience knowing much of the power of the Word of God. His treatise, “On the Bondage of the Will” was a reply to Erasmus, who denied the absolute ruin of man by the fall; in this work he powerfully vindicates the truth, and many years after its publication he declared that he could not review any of his writings with complete satisfaction, unless, perhaps, his Catechism and his “Bondage of the Will.” His translation of the Scriptures in German was a priceless gift to his countrymen; many of his hymns are imperishable and his Commentary on the Galatians will live. Of this last-named work Bunyan writes: “I found my condition in his experience so largely profoundly handled, as if his book had been written out of my heart. This made me marvel; for thus thought I, This man could not know anything of the state of Christians now, but must need write and speak the experience of former days.” He always acknowledged his indebtedness to Augustine, the best of whose writings are, however, lacking in the Scriptural clearness and decision so brightly displayed in his own volumes. Throughout his life and labours he had never troubled himself much about the praise or the abuse of men. After the example of Paul, he went in honour and dishonor, through evil report and good report, along the way which he knew to be pointed out from above. At the age of 63, with the words, “Father, into Thy hands I commend my spirit, for Thou hast redeemed me, O Lord God of truth,” he entered into his heavenly rest.

John Calvin

We now turn to the Swiss, French and English Reformers, and find that, though differences as to the “Sacraments” and Church organization divided them, they were essentially one upon the doctrines of grace; their theology was of the heart, and notwithstanding sometimes embittered controversy, there was no discord as to the foundation. It has been well said that Luther was more the Elijah, Calvin the Paul of the Reformation. “As a theologian, as an expounder of Scripture, as a clear, deep and patient thinker, as a systematic writer on the grand doctrines of truth, as an able administrator, and as a Godly, self-denying, mortified saint and servant of God, Calvin excelled Luther. But in an experience of the terrors of the law and manifested blessings of the Gospel, in a deep acquaintance with temptation and conflict, internal and external, in life and power, so far as he felt the things of God, and in unvaried, unflinching boldness of speech and conduct, Luther as far outshines him.”

Calvinism is a designation by which the doctrines of the sovereign grace of God have been distinguished for the last three centuries. The term derives its descriptiveness from the historical fact that the eminent Reformer, as the chosen servant of God, was qualified by Him to proclaim and defend more prominently than any contemporary or antecedent witness the sublime doctrines in question. Not that these stupendous truths originated with Calvin, but with God Himself. They are an essential part of the revelation of His Word, they are the solidity and security of all real religion, and they form a substantial ingredient in the ministry of the Gospel; hence it is that the Reformers interwove them in their worship and service. When these truths are received in the broken and humble hearts of the disciples of Christ under the “unction from the Holy One” (1 Jn 2:20), they are held in humility and adoration. Calvin’s life was but 55 years, yet how much was compressed therein!—his commentaries, Institutes, and other voluminous works, together with the care of the Churches and pastoral labours. “It is enough to me that I live and die in Christ, who is gain to His people both in life and death.” Farel had seen him a few days before his departure; at nearly 80 years of age he had walked many miles to say farewell. Bees saw him expire—the date was May 27th, 1564. By Calvin’s wish no monument was raised above his grave; they arranged in reverent silence the dust above him and departed. The event was briefly chronicled in the Register thus: “Went to God, Saturday the 27th.”

The same truths were proclaimed by Zwingle and Bullinger, Aecolampandius, Farel and Lefevre, and a multitude of other preachers sent of God to traverse many part of Europe. Our noble English and Scottish Reformers proclaimed the full-orbed Gospel.

John Knox

John Knox’s name is entitled to be placed near those of Luther and Calvin, with the latter of whom he was on terms of intimate friendship. Of small stature and weakly habit of body, he was but 67 when he died, exhausted by the hardships and trials through which he had passed. “What hast thou that thou hast not received?” “I give thanks to my God through Jesus Christ, who has been pleased to give me the victory.” With such words this saint of God entered into rest. He was a preacher rather than a writer, though he has left works of utility. He himself said, “That I did not in writing communicate my judgment upon the Scriptures, I have ever though myself to have most just reason. For considering myself rather called of my God to instruct the ignorant, comfort the sorrowful, confirm the weak and rebuke the proud by tongue and lively voice, in these most corrupt days, than to compose books for the age to come.” His situation was very different from that of the first Protestant Reformers, who found men in ignorance of the doctrines of the Bible and destitute of literature. When Knox appeared the Scripture and many good books had been laid open to the English reader.

John Knox’s House, Edinburgh

Cranmer, Hooper, Ridley and Latimer, with Bucer and Peter Martyr, who were associated with them, were on with the Continental witnesses, as is proved by their writings and testimony of friends and foes. The Articles and Homilies of the Church of England are their work, and with the Marian Martyrs, among whom the first four were numbered, they demonstrated their faithfulness even unto death.

Where Latimer And Ridley Were Burnt.

The “Bill of charges for burning Ridley and Latimer” amounted to £1 5s. 2d. “Such was the money value of the transaction, but the real price paid was the overthrow of the Romish religion in England.” We owe these worthies a great debt of gratitude, but alas! Many have almost forgotten their names and the awful currents of Popish superstition and “religious” infidelity all on in increasing volume. How many of those who profess to love the truth are afraid or ashamed to be called Calvinists! In itself we care little about the name and regret the necessity for its use, but we care everything for what it implies and would never be ashamed of it, for it simply means that we tread “the old paths where is the good way.” “Walk therein and ye shall find rest for your souls” (Jer 6:16).

Gloucester Cathedral, Near Which Bishop Hooper Was Burnt.

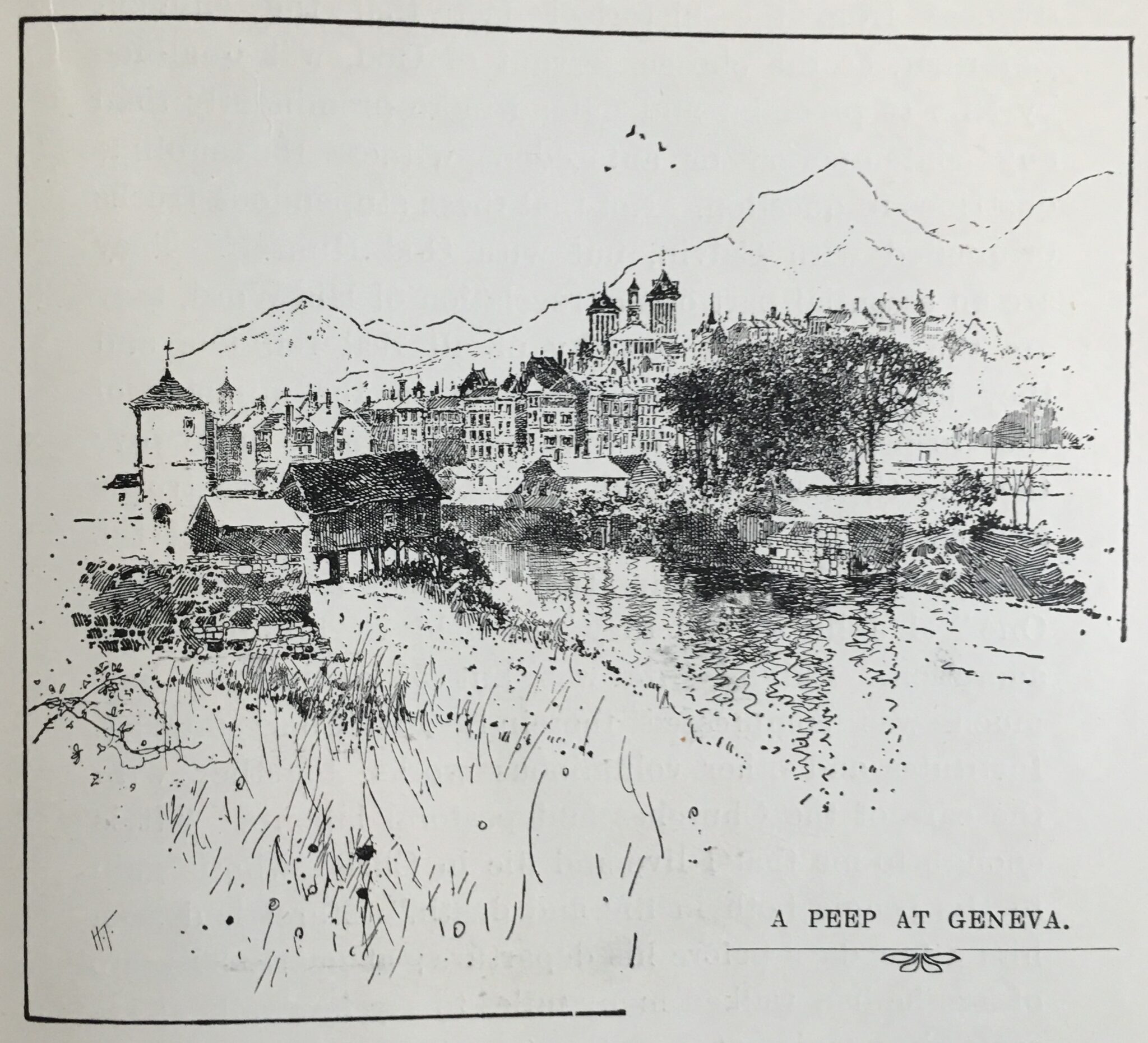

The question often arises as to the reason for the decadence of Protestantism after the Reformers had entered into their rest. One of the chief causes was “the mixed multitude” who, released from the chains of Popery, were received as members of the Churches; those who know the history of Calvin’s troubles at Geneva need not be informed of the difficulties that he had to encounter in his endeavors to mould an ungodly city into the resemblance of a Church of Christ. Political questions became increasingly mingled with religious, and the interests of Governments and Rulers and of Society at large were considered as much or more than the interests of God’s truth. We today face the same peril in an aggravated form, for politics are the bane of certain sections of the professing Church, forming the frequent these of pulpit appeals.

May the Lord cause every servant of His to remember that “it is required in stewards that a man be found faithful” (1 Cor 4:2) and to take to heart the deep saying of James Harington Evans—“That will be a wretched day for the Church of God when she begins to think any aberration from the truth of little consequence.” May the lives and work of the Reformers more deeply influence us:—

“I asked them whence their victory came;

They, with united breath,

Ascribe their conquest to the Lamb,

Their triumph to His death.

They marked the footsteps that He trod,

His zeal inspired their breast;

And following their incarnate God,

Possess the promised rest.”

John Calvin (1509-1564) was a French pastor, theologian, writer and leading reformer during the Protestant Reformation. His most popular works are his “Institutes Of The Christian Religion” and his commentaries on most books of the Bible. He set forth the absolute sovereignty of God in history and salvation, ascribing all glory to the One with Whom we have to do—the TriUne Jehovah. It is from the teachings of Calvin that the Presbyterian churches emerged. The label which bears his name (“Calvinism”) refers not to all of the teachings he espoused, but rather, to those teachings dealing with the salvation of sinners, otherwise known as the Five Points of Calvinism, or, the Doctrines of Grace.

John Calvin's Institutes Of The Christian Religion, Book 1 (Complete)

John Calvin's Institutes Of The Christian Religion, Book 2 (Complete)

John Calvin's Institutes Of The Christian Religion, Book 3