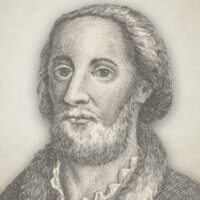

The Life And Testimony Of John Oldcastle

Gospel Magazine 1767:

Sir John Oldcastle was born in the reign of Edward III. He obtained his peerage by marrying the heiress of that Lord Cobham, who with so much virtue and patriotism opposed the tyranny of Richard II. He was much esteemed by King Henry IV but that which made him truly noble was, that God was pleased in those dark times, to reveal the truths of the gospel of Jesus Christ to him, of which he became a zealous professor, and a valiant defender, especially of the godly ministers who were our first reformer Wycliffe’s disciples, whom he protected against the rage of the persecuting clergy, who bore the greatest sway in those popish times.

This occasioned him to become the butt of their envy and malice, insomuch that Arundel, archbishop of Canterbury, calling a synod of the clergy, they appointed twelve inquisitors of heresies to search out Wycliff’s books and disciples. These inquisitors brought in two hundred and forty-fix conclusions, which they collected as heretics out of his books: whereupon they resolved, “That it was not possible to make whole the seamless coat of Christ, (as they said) except some great men were taken out of the way, who were the chief upholders of those heretics and heresies, amongst whom the Lord Cobham was esteemed the principal, who in the dioceses of Canterbury, London, Rochester, and Hereford, had entertained, maintained, and set up to preach, such as were not licensed by the bishop, and who himself held heretical opinions about the sacraments, images, pilgrimages,” &c.

The regard which Lord Cobham discovered on all occasions, to the reformers, easily pointed him out to the clergy as the principal person among the Wicklivites: not indeed made he any secret of his belief of the gospel doctrines. It was publicly known that he had been at a great expense in collecting and transcribing among the common people. It was also known that he maintained a great number of the disciples of Wycliff, as itinerate preachers in many parts of the country. These things drew upon him the resentment of the clergy in general, and made him more obnoxious to that body of men than any other person at that time in England. Therefore they concluded, that without any further delay a process should be commenced against him as against a most pernicious heretic. But some that were not so violent as the rest, advised that the Lord Cobham was a great man, and of a family of distinction, and much in favor with the king at that time, that therefore they should acquaint the king with this business, and endeavor to procure his approbation and consent before they summoned him.

This counsel was approved of, and therefore Arundel, with his other bishops, directly applied to the king, and laid before his majesty very grievous complaints against the Lord Cobham. The king patiently heard these blood-thirsty prelates, for in those dark days they kept the king in awe, yet he immediately desired, that on account of Lord Cobham’s nobility and family they would deal mildly and favorably with him, and endeavor rather to recover him by persuasion than with rigor. And he also told them, that if they would have a little patience, he would seriously discourse with him about those matters.

They being for that time pacified, the king sent for Lord Cobham, and advised him to be an obedient child, and to submit to the church, and also to acknowledge himself culpable. To whom this Christian nobleman answered: “You, most worthy prince, I am always willing to obey, forasmuch as I know you to be the minister of God, bearing the sword for the punishment of evil-doers, and for the praise of them that do well: unto you, next to my eternal God, I owe my whole obedience, and submit all that I have to you, being ready at all times to do whatsoever you shall in the Lord command me: but as touching the pope and his spirituality, I owe them neither state nor service, knowing him by the scriptures to be the great anti-christ, the son of perdition, the open adversary of God, and the abomination standing in the holy-place.”

This answer of the Lord Cobham so exceedingly shocked the king, that turning away in visible displeasure, he withdrew from that time every mark of favor from him.

The archbishop becoming no triumphant, immediately cited the Lord Cobham to appear before him on a fixed day: but that courages nobleman would not suffer the summoner to enter his gate. Upon this the archbishop ordered the citation to be fixed upon the doors of the cathedral of Rochester, which was only three miles from Cowling-castle, the Lord Cobham’s seat; but it was immediately torn away by unknown hands.

The day appointed for his appearance was the eleventh of September, on which day the archbishop and his associates sat in consistory. The accused party not appearing, the archbishop pronounced him contumacious, and after receiving an aggravated charge against him, which he did not examine, he excommunicated him without farther ceremony. Having proceeded thus far, he armed himself with terrors of the new law, and threatening direful anathema, called in the civil power to assist him.

The Lord Cobham saw himself in great danger, and therefore put in writing a Confession of his Faith, wherein also he answered to four of the chief articles charged against him, and went with it to the king, trusting to find mercy at his hands. In this Confession he recites the apostle’s Creed; then he professes his belief in the Trinity, and acknowledges Christ as the only head of the church. He professes to believe that in the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper are contained Christ’s body and blood under the similitude of bread and wine. He concluded the Confession of his faith thus: “All the promises I believe particularly, and generally all that God hath left recorded in his holy word; and therefore I desire you, my liege Lord and most worthy King, that this confession of mine may be justly examined by the most godly, wise and learned men of your realm. If it be found agreeable to God’s word let it be allowed; otherwise let it be condemned: provided always that I be taught a better belief by the holy scriptures; and I will at all times most reverently submit to the same.”

The king coldly ordered it to be given to the archbishop. Lord Cobham then offered to bring an hundred knights, who would bear testimony to the innocence of his life and opinions. He also offered, after the law of arms, to fight with any man living, Christian or heath, in the defense of the faith, the king and his council being excepted. Lastly, he protested that he would refute no correction that should be inflicted upon him according to the laws of God. Notwithstanding the king suffered him to be personally summoned in his presence to appear before the archbishop. Wherefore the Lord Cobham said, “That he had appealed from

the archbishop, and therefore he ought not to be his judge.” At which the king was much offended, and when he refused to be sworn to submit to the archbishop, he was arrested and sent to the tower hill the day of his appearance.

On the twenty-third day of September the archbishop sat in the chapter-house of St. Paul’s, with the bishops of London and Winchester, when Lord Cobham was brought before them by Sir Robert Morley, lieutenant of the tower. He told them that he was ready to rehearse the Confession of his Faith, if they would give him leave; and that he would read those articles upon which he supposed he was called in question; that any farther examination on those points was needless, for he was entirely fixed: he said, “That which I have written I stand to, even to death.”

The bishops were amazed at his courageous answer: and leave being given he read a paper, which contained his Confession on four points, “The Sacrament of the Lord’s supper, Penance, Images, and Pilgrimages.” With regard to the first point, he held, as hath been already mentioned, that Christ’s body was really contained under the form of bread. With regard to the second, he thought penance for sin, as a sign of contrition, was useful and proper. With regard to images, he thought them only allowable to remind men of heavenly things, and that he who really paid divine worship to them was an idolator. With regard to the last point, he said that all men were pilgrims upon earth traveling towards happiness or misery; but as to pilgrimages undertaken to the shrines of saints, they were frivolous, he thought, and ridiculous.

Having read this Confession, he delivered it to the archbishop, who having examined it, told him, that what it contained was in part truly orthodox; but that in some parts he was not sufficiently explicit. There were other points the archbishop said, in which it was expected he should give his opinion. Lord Cobham refused to make any other answer, telling the archbishop he was fixed in his opinion. He was then sent to the tower till the Monday following.

On the day appointed the archbishop appeared in court, attended by three bishops, and four heads of religious houses. As if he had been apprehensive of a tumult, he removed his judicial chair from the cathedral of St. Paul’s to a more private place in a Dominican convent; and had the area crowded with a numerous throng of friers and monks, as well as seculars. Amidst the looks of these fiery men, Lord Cobham, attended by the lieutenant of the tower, walked up undaunted to the place of hearing.

The archbishop accosted him with an appearance of great mildness; and having curiously run over what had hitherto passed in the process, told him, he expected at their last meeting to have found him suing for absolution; but that the door of reconciliation was still open, if reflection had yet brought him to himself. “I have trespassed against you in nothing, said the zealous nobleman: I have no need of your absolution.”

Then kneeling down, and lifting up his hand to heaven, he broke out into this pathetic exclamation: “I confess myself here before thee, O almighty God, to have been a grievous sinner. How often have ungoverned passions misled my youth? How often have I been drawn into sin by the temptation of the world? Here absolution is wanted. O my God, I humbly ask thy mercy!”

Then rising up, with tears in his eyes, and strongly affected with what he had just uttered, he turned to the assembly, and stretching out his arm, cried out with a loud voice: “Lo! These are your guides, good people. For the most flagrant transgressions of God’s moral law was I never once called in question by them: I have expressed some dislike to their arbitrary appointments and traditions, and I am treated with unparalleled severity. But let them remember the denunciation of Christ against the Pharisees: all shall be fulfilled.”

The grandeur and dignity of his manner, and the vehemence with which he spoke, threw the court into some confusion. The archbishop however attempted an awkward apology for the treatment of him, and then turning suddenly to him, asked him what he thought of the paper that had been sent to him the day before? And particularly what he thought of the first article, with regard to the holy sacrament?

“With regard to the holy sacrament, answered Lord Cobham, my faith is, that Christ sitting with his disciples, the night before he suffered, took bread, and blessing it, brake it, and gave it to them, saying, Take, eat, this is my body, which was given for you: Do this in remembrance of me.—This is my faith, Sir, with regard to the holy sacrament. I am taught this faith by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Paul.”

Do you believe in the determination of the holy church? “I do not. I believe the scriptures, and all that is founded upon them: But in your idle determinations I have no belief. To be short with you, I cannot consider the church of Rome as any part of the Christian church. Its endeavor is to oppose the purity of the gospel, and to set up in its room I know not what absurd constitutions of its own.”

This free declaration threw the whole assembly into great disorder. Every one exclaimed against the audacious heretic. Among others, the prior of the Carmelites, lifting up his eyes to heaven, crying out, “What desperate wretches are these scholars of Wycliff!”

“Before God and man, answered Lord Cobham, with vehemence, I here profess that before I knew Wycliff, I never abstained from sin; but after I was acquainted with that good man, I saw my errors, and I hope reformed them.”

The very great spirit and resolution with which Lord Cobham behaved on this occasion, together with the quickness and pertinence of his answers, Mr. Fox tells us, so amazed his adversaries, that they had nothing to reply. The archbishop was silent. The whole court was at a stand.

At last one of the doctors, taking a copy of the paper which had been sent to the tower, and turning to Lord Cobham, told him, That the design of the present meeting was not to spend the time in idle altercation, but to come to some conclusion. “We only, said he, desire to know your opinion upon the points contained in this paper.” He then desired a direct answer, whether, after the words of consecration, there remained any material bread?

“I have told, answered Lord Cobham, that my belief is, that Christ’s body is contained under the form of bread.”

He was again asked, Whether he thought Confession to a priest of absolute necessity?—He said, “he thought it might be in many cases useful to ask the opinion of a priest, if he were a learned and pious man; but he thought it by no means necessary to salvation.”

He was then questioned about the pope’s right to St. Peter’s chair.—“He that followeth Peter the nighest in good living, he answered, is next him in succession. You talk, said he, of Peter; but I see none of you that followeth his lowly manners, nor indeed the manners of his successors till the time of Sylvester.”

But what do you affirm of the pope—“That he and you together, replied Lord Cobham, make whole the great antchrist. He is the head, you bishops and priests are the body, and the begging friers are the tail, that covers the filthiness of you both with lies and sophistry.”

He was afterwards asked, What he thought of the worship of images and holy relics?—“I pay them, answered Lord Cobham, no manner of regard. Is it not, said he, a wonderful thing that these saints, so disinterested upon earth, should after death become suddenly so covetous? It would indeed be wonderful did not the pleasurable lives of priests account for it.”

Having thus answered the four articles the archbishop said, “The day is wearing apace: we must come to some conclusion. Take your choice of this alternative: submit obedience to the orders of the church, or endure the consequence.” “My faith is fixed, answered Lord Cobham, do with me what you please.” The archbishop then standing up, pronounced aloud the sentence of condemnation.

Lord Cobham, with great cheerfulness, subjoined, “You may condemn my body: my soul, I am well assured, you can do not harm to it, no more than Satan did to Job’s soul. He that created it will of his infinite mercy save it, I doubt not: And as for the Confession of my Faith, I will stand to it, even to the very death, by the grace of my eternal God: And then turning to the people, he said with a loud voice: For God’s sake be well aware of these men, otherwise they will beguile you, and lead you blindfold into eternal destruction with themselves. Having said this, he fell on his knees, and prayed for his enemies, saying, Lord God eternal, I beseech thee of thine infinite mercy to forgive my persecutors, if it be thy blessed will!” He was then sent back to the tower.

These proceedings of the clergy were very unpopular. Few men were generally more esteemed than Lord Cobham. The clergy were in some degree perplexed, and saw the bad consequences of going farther, but imagined they saw worse in receding. What seemed best, and was most agreeable to the genius of popery, was to endeavor to lessen his credit among the people. With this view many scandalous aspersions were spread abroad by their emissaries. Mr. Fox tells us, they scrupled not even to publish a recantation in his name, and gives us a copy of it. Lord Cobham, in his own defense, had a paper posted up in some of the most public places in London, declaring that he had never varied in any point from the first Confession of his Faith.

Some months had now elapsed since Lord Cobham had been condemned: nor did the archbishop and his clergy seem to have come to any resolution. They thought it imprudent yet to proceed to extremities. Out of this perplexity their prisoner himself extricated them. By unknown means he escaped out of the tower, and taking the advantage of a dark night, evaded pursuit, and arrived safe in Wales; where, under the protection of some of the chiefs of that country, he secured himself against his enemies, and was there four years.

His enemies, after many fruitless attempts, engaged the lord Powis in their interest, a very powerful person in those parts, and in whose lands the Lord Cobham was supposed to lie concealed. In the midst of his supposed security he was taken, carried to London in triumph, and put into the hands of the archbishop of Canterbury. The superiority which the clergy had now obtained, both in the parliament and in the cabinet, soon convinced him that no mercy was to be shown to him by them: And being brought before the house of Lords, and not declining from his former profession, he was condemned. With every instance of barbarous insult, which enraged superstition could invent, he was dragged to execution. St. Gile’s-Fields was the place appointed; where, both as a traitor and a heretic, he was hung up in chains upon a gallows, and fire being put under him, was burnt to death. Thus this godly, zealous, and courageous champion of Jesus Christ suffered martyrdom, in the year of our Lord 1417.

This courageous nobleman, who was qualified to be an ornament to his country, fell a sacrifice to the unfeeling race and barbarous superstition of the papists. He was in great favor with his prince, Henry V till the clergy suggested to the king that this Lord Oldcastle, and other Wicklivites, to the number of twenty thousand, were assembled in a hostile manner, and threatened to murder the king, and all that should oppose them. Wherefore the king went at midnight, with what men he could readily muster, and attacked a small assembly of about eighty, with a godly minister: twenty were killed, and sixty taken. They were assembled in St. Gile’s-Fields, to hear the gospel preached in those times of persecution. seeing they had not liberty to do it as a proper time and place. Thirty-seven were condemned, and some of them were handed and burnt.

Lord Cobham was a nobleman of uncommon abilities and very extensive talents; well qualified either for the cabinet or the field. In conversation he was remarkable for his ready wit. His acquirements were very great. No species of learning at that time in esteem, had escaped his attention. His desire of knowledge first brought him acquainted with the opinions of Wycliff. We are told that the novelty of them engaged his curiosity, and that he examined them as a philosopher, and in the course of his examination became a Christian. It appears that the grace of God reached his heart, and that he was truly convinced, and embraced the truths of the gospel, and the way of salvation by the blood and righteousness of Jesus Christ, and that his eyes were opened to see the superstitions and inventions of the popish religion,

We may consider Lord Cobham as having a principal hand in propagating and establishing the evangelical doctrines of Wycliff against the error of popery. He shewed the world that religion was not merely calculated for the cloister, but that it might in reality be introduced among those in high stations, and that it was not below a nobleman or gentleman to lose his life in its defense, and be a martyr for the gospel of Jesus Christ; and that the true disciples of the blessed Redeemer, when they are called to it, ought to lay down their lives for his sake, Luke 14:26.

John Oldcastle (?-1417) was a nobleman of great abilities, and an eminent disciple of Wycliffe, the first Reformer, who was persecuted by the popish clergy for his zealous and steady profession of the gospel doctrines of the reformation. He was crowned with martyrdom in St. Gile’s-Fields, near London, where he was hung up in chains upon a gallows, and fire being put under him, was burnt, in the year of Christ 1417.