The Life And Testimony Of John Bunyan

The Sower 1886:

John Bunyan was born at Elstow, near Bedford, in 1628. His father was a tinker, and, concerning his humble birth, Bunyan says, “My descent was of a low and inconsiderable generation, my father’s house being of that rank that is meanest and most despised of all the families of the land.” But, poor as his parents were, they did not neglect sending their children to school, for which John felt very grateful in after years.

At a very early age he acquired the sad habit of swearing, for which he became notorious, but he proved “the way of transgressors to be hard! for, after spending a day thus in sin, he was scared and terrified at night with fearful dreams, and apprehensions of devils and wicked spirits, who, as he thought, were labourring to carry him away. At times, thoughts of the day of judgment would fill his mind that, when in the midst of his play, he was often cut down and miserable.

Having thus early in life (for he was not then ten years old) contracted such evil habits, they grew up with him, becoming part of his nature; and, as he got older, his terrors left him, and he became more hardened in sin, until he married, when, by reading two books which his wife possessed, which were all the dowry she had, and partly by her influence, he was led to attend the parish church twice every Sunday, but he was totally ignorant of the nature of sin and his need of a Saviour.

The times in which Bunyan lived were very corrupt. The king, in 1618, issued a permit to everybody who should go to evening prayer on the Lord’s Day, to divert themselves in the afternoon with such exercises as leaping, dancing, playing at bowls, shooting with bows and arrows, as likewise, to rearing May-poles, &c., but those who refused to come to prayers were forbidden these sports. Bunyan was only too glad to avail himself of such a law by sporting and profaning the day which the Lord has set apart for His worship.

But one Sunday morning he went to church as usual, when the minister spoke of the evil of Sabbath-breaking, whereupon he felt in his conscience the sermon was intended for him; and, for the first time, he experienced what guilt was, going home sad at heart. But, as soon as he had dined, he shook the sermon out of his mind, and went to his sports with increased delight. But the same day, as he was in the midst of a game at “cat,” and having struck it one blow, just as he was going to strike another, suddenly a voice from heaven sounded into his soul, which said, “Wilt thou leave thy sins and go to heaven, or have thy sins and go to hell?” At this he was in an exceeding maze; wherefore, leaving his cat upon the ground, he looked up to heaven and saw, with the eyes of his understanding, Jesus Christ looking down upon him very greatly displeased, and threatening him with grievous punishment for these and other ungodly practices. He stood musing before his companions, when it was suggested to his mind that it was too late to expect mercy, and, despair getting fast hold of him, he made a desperate resolve to go on with his games, determining to have his fill of pleasure before he went to hell, as he thought. Wherefore he went on in sin with great greediness, cursing and swearing and playing the mad-man, for which he was once reproved by a woman, who was herself a loose, ungodly creature, saying it made her tremble to hear him, and that he was the most ungodly fellow for swearing that ever she heard in her life, at which he was silenced and put to shame, and wished in his heart that he might be a little child again, that his father might teach him to speak without swearing.

How it came to pass he knew not, but he did from that time so discontinue it that he became a wonder to himself, and shortly after, putting on an outward form of religion, he thought he “pleased God as well as any man in England.”

In the providence of God, John Bunyan removed to Bedford, to follow his calling as a tinker; and in one of the streets of that town he came where there were three or four poor women talking about the things of God, “and methought,” says he, “they spake as if joy did make them speak—as if they found a new world, and were people that dwelt alone, and were not to be reckoned among their neighbours,” at which his own heart began to shake, for such things as they talked of had never entered his mind. He, however, felt he must listen to them, and continued going again and again, and found his heart softened thereby; and when they brought Scripture to prove their assertions, he felt convinced of the truth of what they said, and pondered the things in his heart. Thus God, in the riches of His free grace and boundless compassion, brought him to that wisdom which Moses exhorts to—“O that they were wise, that they understood this, that they would consider their latter end!”

The limits of our article will not allow us to follow him in this good work. Suffice it to say, the Lord led him to a greater knowledge of himself as a lost, ruined, guilty, needy soul, and in due time showed him he was just the character Jesus came to save, making him to rejoice in Him as his Saviour, as described in his “Pilgrim’s Progress,” where Christian arrived at the cross, from whence he went on singing—

“Blest cross, blest sepulchre, blest rather be

The Man that there was put to shame for me.”

Bunyan was not only a tinker, but a soldier. He served in the Parliamentary army at Leicester, at the time of the Battle of Naseby, where, upon one occasion, he was called out as a sentinel, but another soldier volunteered to do duty for him, and that very man was shot through the head while at his post. Thus the Lord, whose tender care was over Bunyan, spared his life that he might be a renowned soldier of the cross.

Now, as the Lord chose Paul to be the great Apostle, who to the disciples seemed the most unlikely person, so He chose John Bunyan to preach the Gospel, to the astonishment of those that knew his former life. He had not, however, laboured more than five years before he was apprehended by the civil powers, on November 12th, 1660, at Samsell, near Harlington, where he was engaged to preach. His hearers were met together, and after he had given out his text, “Dost thou believe on the Son of God?’’ the constable came with a warrant to take him prisoner, at which Bunyan was not much moved, for he remarked, “We might have been apprehended as thieves, or murderers, or for other wickedness; but, blessed be God, it is not so. We suffer as Christians, for well doing.” He might have escaped, it being rumoured that a warrant was issued against him, but he was determined to stand his ground.

He was taken before the justices of the peace, and by them committed to Bedford Gaol, to await the sessions.

Bunyan was afterwards tried before five or six justices, but they could find nothing against him, except it was in the law of his God. His chief offences were—he did not use the Common Prayer Book, and that he went about teaching in certain places of meeting, to the disparagement of the Church of England. For these acts of Nonconformity he laid in the miserable cell for about twelve years; but his God was with him, and made the prison like a palace to him. He was often far happier in the prison than the king was upon his throne, or the rich, “who fared sumptuously every day.” He never before had such an inlet into the Word of God, and doubtless he has preached to millions of the human race by his confinement, who, but for that—would never have heard of him, for by it he became very popular; so the means used to stop the spread of truth were, by God’s blessing, the cause of more widely circulating it.

It was there he wrote several books, the materials for which were not borrowed, for his library in prison consisted only of the Bible and “Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.”

During the early part of his imprisonment, the Lord gave him favour (as He did Joseph) in the eyes of the jailer, who allowed him occasionally to visit his friends, and to preach in the villages and woods. It is said that many of the Baptist congregations in Bedfordshire owe their origin to his midnight preaching; but this coming to the ears of the justices, the humane jailer well-nigh lost his place through it, and he was seldom afterwards permitted to go out of doors.

It was an anxiety to Bunyan, when he was first imprisoned, to know what would become of his wife and four children, one of whom was blind; but the Lord took care of them, and, in His providence, enabled him to work for them in prison, as it is recorded of him. “Nor did he eat the bread of idleness, for there,” says the writer, “I have witnessed that his own hands have ministered to his family’s necessities, making many hundred gross of long-tagged laces, which he had learned to make in prison.”

John Bunyan, with many other prisoners, was liberated indirectly through the intercession of a Quaker; and, about the time of his liberation, an Act was passed granting certain indulgences to Nonconformists. It was enacted partly to conciliate the Roman Catholics, who, with others, were suffering persecution because they dissented from the form of worship used by the Church of England.

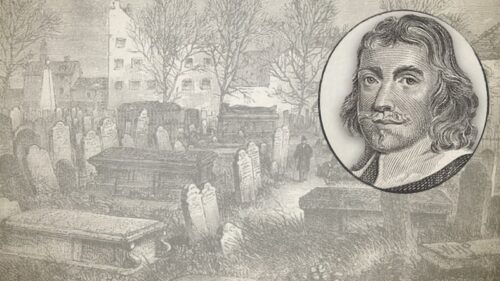

Bunyan’s imprisonment extended over a period of twelve years, during which time he was confined in the county gaol. After being at liberty for a period of two years, he was again imprisoned for six months, but this time in the town gaol on the bridge, of which we are able to give our readers an excellent engraving.

It was during this short imprisonment that he is supposed to have conceived the plan of his famous allegory, and, indeed, wrote the chief portion of the first part; but it is thought that he was liberated before he had quite completed it. After the Pilgrims’ visit to the Delectable Mountain, it says, “So I awoke from my dream.” This is supposed to mark the point Bunyan had reached in his book when the order came for his liberation and the rest of his dream was written at home.

He lived and preached the Gospel for about sixteen years after he was let out of prison, and both he and his writings became very popular. Upon one occasion, the King remonstrated with Dr. John Owen because he went to hear a tinker preach, to which Owen replied, “May it please your Majesty, had I the tinker’s abilities, I would most gladly relinquish my learning.”

Bunyan died in London, August 12th, 1688, and his remains were interred in Bunhill Fields burying-ground, where, of late, years, an elaborate tomb has been erected to his memory; and, within the last few years, Bedford, the town of his imprisonment, has made room for a handsome monument to perpetuate his memory. “The memory of the just is blessed.”

John Bunyan (1628-1688) was a sovereign grace preacher, author and poet. He was appointed the pastor of a non-conformist church in Bedford. Although he was a baptized believer, it is questionably whether the Bedford congregation was a Baptist church. He was an open-communionist, welcoming to the Lord’s Table all who professed faith in Christ. An open Table of this kind sidelines the ordinance of Baptism, thereby undermining a ‘Baptist’ identity. Nevertheless, Bunyan nurtured strong views on sovereign grace and is best known for his Christian allegory, “The Pilgrim’s Progress”.