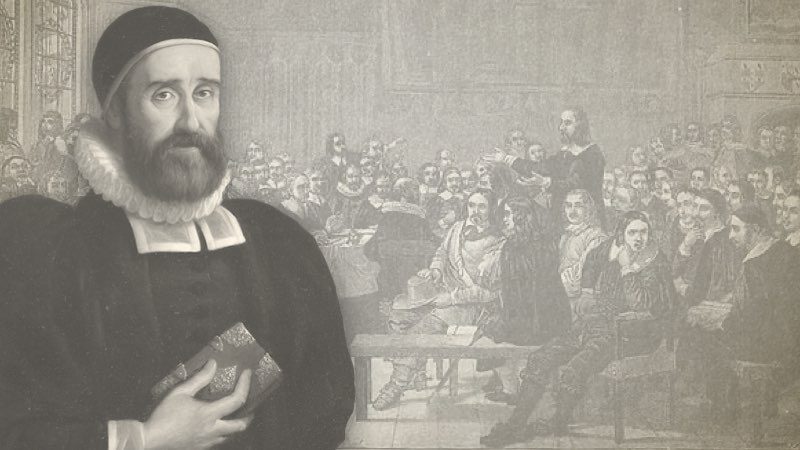

The Life And Ministry Of William Twisse

Dictionary Of National Biography, 1885:

William Twisse D.D. (1578?–1646), puritan divine, was born at Speenhamland in the parish of Speen, near Newbury, about 1578. The family name is variously spelled Twysse, Twiss, Twyste, and Twist. His grandfather was a German, his father a clothier. Thomas Bilson [q. v.] was his uncle (Kendall). While at Winchester school where he was admitted, aged 12, in 1590 (Kirby), he was startled into religious conviction by the apparition of a ‘rakehelly’ schoolfellow uttering the words ‘I am damned.’ From Winchester he went as probationer fellow to New College, Oxford, in 1596, his eighteenth year (ib.), was admitted fellow 11 March 1598, graduated B.A. 14 Oct. 1600, M.A. 12 June 1604, and took orders. His reputation was that of an erudite student, equally remarkable for pains and penetration. Sir Henry Savile [q. v.] had his assistance in his projected edition of Bradwardine’s ‘De Causa Dei contra Pelagium’ (published 1618), which Twisse, before 1613, had transcribed and annotated. His expository power was shown in his Thursday catechetical lectures in the college chapel. To his plain sermons, delivered every Sunday ‘in ecclesia parochiali Olivæ’ (St. Aldate’s), he drew large numbers of the university. He graduated B.D. on 9 July 1612.

Twisse’s popularity was increased by his readiness on an unexpected occasion in 1613. A Hebrew teacher at Oxford, Joseph Barnatus, had ingratiated himself with Arthur Lake [q. v.], warden of New College, by offering to receive Christian baptism, to be administered on a Sunday at St. Mary’s after a special sermon by Twisse. But on the Saturday ‘bonus Josephus clanculum se subducit,’ and, though dragged back to Oxford, declined baptism. Twisse preached a tactful sermon which saved the situation. Shortly afterwards he was made chaplain to Elizabeth, queen of Bohemia [q. v.], and attended her on her journey with her husband to Heidelberg (April–June 1613). Twisse evidently expected a long absence; for he disposed of his small patrimony (30l. a year), giving it in trust to his brother. But before he had been two months at Heidelberg he was recalled. On the presentation of his college he was instituted (13 Sept. 1613) to the rectory of Newton or Newington Longueville, Buckinghamshire. He proceeded to the degree of D.D. on 5 July 1614. His life for some years was that of a recluse scholar, studying hard, yet not neglecting his flock. On 22 March 1618–19 Nathaniel Giles had been instituted to the rectory of Newbury. The municipal authorities were anxious to secure Twisse, who accordingly exchanged with Giles, and was instituted to Newbury on 4 Oct. 1620. Further preferments he resolutely declined, refusing the provostship of Winchester, and rejecting a prebend in Winchester Cathedral, as lacking music for the singing and rhetoric for the preaching, and not skilled to stroke a cathedral beard canonically (ib.) He declined an invitation to a divinity chair at Franeker. He felt the pressure of his duties as age crept on, and was tempted by the offer of Robert Rich, second earl of Warwick [q. v.], to give him a better living (Benefield, Northamptonshire), with a less laborious cure. Before accepting it he saw Laud, with whom he had been intimate at Oxford, about the appointment of his successor, Newbury being a crown living. Laud promised to meet Twisse’s requirements, adding that he would assure the king that Twisse was no puritan. He at once decided to stick to his post. His puritanism was not aggressive, and was chiefly doctrinal. He did not read the ‘Declaration of Sports,’ and protested against it with quiet firmness. It was a tribute to his commanding eminence as a theologian and to his moderate bearing that, at the king’s desire, he was subjected to no episcopal censure. His bishop was John Davenant [q. v.], who certainly had no inclination to interfere with Twisse unless compelled.

As a controversialist Twisse was courteous and thorough, owing much of his strength to his accurate understanding of his opponent’s position. Baxter well describes him as using a ‘very smooth triumphant stile.’ The defence of the puritan theology was congenial to him; and in an age of transition to positions more or less Arminian the acumen of Twisse was constantly exercised in maintaining the stricter view. No contemporary theologian gave him more trouble than Thomas Jackson (1579–1640) [q. v.] He had less difficulty in dealing with the more sharply defined antagonism of Henry Mason [q. v.], Thomas Godwin, D.D. [q. v.], and John Goodwin [q. v.] Men of his own school, like John Cotton of New England, found him a watchful critic, always armed to resist deviations in doctrine.

At the outset of the civil war Prince Rupert had hopes of engaging Twisse on the side of the king. His sympathies were with the cause of the parliament, but he thought the war would be fatal to the best interests of both parties. In ecclesiastical affairs he had a dread of revolutionary measures, and the policy of laying hands on the patrimony of the church he viewed as inimical to religion. He had been on the sub-committee in aid of the lords’ accommodation scheme of March 1641. There is no reason for doubting that his own preference was always for the modified episcopacy then recommended. He was nominated to the Westminster assembly of divines in the original ordinance of June 1643, was unanimously elected prolocutor and preached at the formal opening of the assembly on 1 July, regretting in his sermon the absence of the royal assent, and hoping it might yet be obtained. He had very unwillingly accepted the post; indeed, his health was unequal to its demands. Robert Baillie, D.D. [q. v.], thought it a ‘canny convoyance of these who guides most matters for their own interest to plant such a man of purpose in the chaire.’ He describes him as ‘very learned in the questions he hes studied, and very good, beloved of all and highlie esteemed; but merely bookish … among the unfittest of all the company for any action.’ Baillie’s keen ear detected that Twisse was not used to pray without book, adding, ‘After the prayer he sitts mute.’ The minutes show that his part in the assembly was purely formal, and he owns himself ‘unfit for such an employment that divers times do fall upon me’ (3 Jan. 1644–5). It fell to Cornelius Burges, D.D. [q. v.], to supply, ‘so farr as is decent, the proloqutor’s place’ (Baillie). On 1 April 1645 it was reported to the assembly that the prolocutor was ‘very sick and in great straits.’ He had received no profits from Newbury, and but a small stipend (1643–5) as one of three lecturers at St. Andrew’s, Holborn. On 30 March 1645 he had fainted in the pulpit (‘procumbit in pulverem,’ Kendall), and henceforth kept his bed. Though a man of some estate—for his will (9 Sept. 1645; codicil 30 June 1646; proved 6 Aug. 1646) disposes of the manor of Ashamstead, Berkshire, and other property—the confusion of the times had deprived him of income. Parliament voted him 100l. (4 Dec. 1645), which does not seem to have been paid in full; on 26 June 1646 the assembly sent him 10l., with the assurance ‘that there hath been no money paid by any order of parliament to his use that hath been detained from him.’

Twisse died in Holborn on 20 July 1646, and on 24 July, with all the pomp of a public funeral, was buried in Westminster Abbey, ‘in the south side of the church, near the upper end of the poore’s table, next the vestry.’ By royal mandate of 9 Sept. 1661 his remains, with others, were disinterred and thrown into a common pit in St. Margaret’s churchyard, the site being in the sward between the north transept and the west end of the abbey. An oil painting of him, done in 1644, is in the vestry of St. Nicholas, Newbury. Bromley says his portrait, engraved by T. Trotter, is in the ‘Nonconformist’s Memorial,’ but this is an error. He was twice married: first, before 1615, to a daughter of Robert Moor [q. v.]; secondly, to Frances, daughter of Barnabas Colnett of Combley, Isle of Wight. At the time of his death he was a widower with four sons and three daughters. His son William, born in 1616, was fellow of New College, Oxford (1635–50); his son Robert (d. 1674) published in 1665 a sermon preached at the New Church (now Christ Church), Westminster, ‘on the anniversary of the martyrdom’ of Charles I. Parliament voted 1000l. towards the support of his children, but the money does not seem to have been paid.

Twisse published: 1. ‘A Discovery of D. Jacksons Vanitie,’ 1631, 4to. 2. ‘Vindiciæ Gratiæ, Potestatis ac Providentiæ Dei,’ Amsterdam, 1632, fol.; 1648, fol. 3. ‘Dissertatio de Scientia Media,’ Arnheim, 1639, fol. 4. ‘Of the Morality of the Fourth Commandment,’ 1641, 4to; with new title, ‘The Christian Sabbath defended,’ 1652, 4to. 5. ‘A Brief Catecheticall Exposition of Christian Doctrine,’ 1645, 8vo. 6. ‘A Treatise of Mr. Cotton’s … concerning Predestination … with an Examination thereof,’ 1646, 4to. Posthumous were: 7. ‘Ad … Arminii Collationem … et … Corvini Defensionem … Animadversiones,’ Amsterdam, 1649, fol. 8. ‘The Doctrine of the Synod of Dort and Arles (sic) reduced to the Practise, with an Answer thereunto’ [1650], 4to. 9. ‘The Doubting Conscience resolved,’ 1652, 12mo. 10. ‘The Riches of God’s Love … consisted with … Reprobation,’ Oxford, 1653, fol. 11. ‘The Scriptures’ Sufficiency,’ 1656, 12mo; commendatory epistle (29 April 1652) by Joseph Hall, bishop of Norwich. According to Kendall, he left some thirty unpublished treatises. His manuscripts, Wood says, were carefully kept by his son Robert till his death. His fifteen letters (2 Nov. 1629–2 July 1638) to Joseph Mead [q. v.] are printed in Mead’s ‘Works,’ 1672, bk. iv. The collection of ‘Guilielmi Twissi … Opera,’ Amsterdam, 1652, fol., 2 vols., consists of Nos. 2, 3, and 7 above, bound together, with additional title-page.

[Tuissii Vita et Victoria, by George Kendall [q. v.], appended to Fur pro Tribunali, 1657, is the main authority; it is closely (not always carefully) followed in Clarke’s Lives of Sundry Eminent Persons (1683, pp. 13 sq.), less closely by Brook (Lives of the Puritans, 1813, iii. 12 sq.), and by Chalmers (General Biographical Dictionary, 1816, xxx. 118 sq.). See also Wood’s Athenæ Oxon. (Bliss), iii. 169 sq.; Wood’s Fasti (Bliss), i. 285, 303, 348, 359; Foster’s Alumni Oxon. 1892, iv. 1525; Fuller’s Church History, 1655, xi. 199; Fuller’s Worthies, 1662, ‘Barkshire,’ p. 96; Reliquiæ Baxterianæ, 1696, i. 73; Bromley’s Catalogue of Engraved British Portraits, 1793, p. 91; History of Newbury, 1839, p. 106; Lipscomb’s Buckingham, 1847, iv. 266; Mitchell and Struthers’s Minutes of the Westminster Assembly, 1874, passim to p. 258; Chester’s Registers of Westminster Abbey, 1876, pp. 140, 151, 153; Money’s Hist. of Newbury, 1887, pp. 503 sq.]William Twisse (1578-1646) was an English scholar, theologian and preacher. In 1643, Parliament ordered his nomination as prolocutor to the Assembly of Divines. He was a staunch Calvinist, defending the grace of God against the leading free-will (Arminian) advocates of his day. His approach to sovereign grace was based on the framework of the Supralapsarian order of God’s decree.