Biographical Sketches Of Isaac Watts

1. John Gadsby, “Hymn-Writers And Compilers”

Isaac Watts was born at Southampton, July 17th, 1674. He was the eldest son, there being four sons and five daughters, of Mr. Isaac Watts, the master of a very flourishing boarding-school in that town, which was in such reputation that gentlemen’s sons were sent to it from America and the West Indies. His parents, being conscientious Nonconformists, had suffered much from the persecuting measures of Charles II, his father having been imprisoned more than once because he would not attend the church. During his imprisonment, his wife sometimes sat near the prison-door, suckling her son Isaac.

When about 7 years old, Isaac was desired by his mother to write her some lines, as was the custom with the other boys after the school hours were over, for which she used to reward them with a farthing. Isaac obeyed, and wrote the following:

“I write not for a farthing, but to try,

How I your farthing-writers can outvie.”

The precise time when effectual grace laid hold of his heart, I have not been able to learn. Dr. Jennings says, “Through the power of divine grace, he was not only preserved from criminal follies, but had a deep sense of religion on his heart betimes.” Some gentlemen at Southampton offered to defray the expenses of his education at one of the Universities, but he declined it, saying he was determined to take his lot amongst the Dissenters. Accordingly, in the year 1690, he was sent to London, for academical education under Mr. Thomas Rowe, and in 1693, in his 19th year, he joined in communion with the church under the pastoral care of his tutor.

While at this academy, he wrote two volumes of Latin dissertations, and two English dissertations. One of the latter was on the subject of justification through the imputed righteousness of Christ; in which he says, “The devil has used many artifices to subvert us, among which this is a principal one, namely, filling men’s minds with wrong opinions concerning it, by representing it as an unholy doctrine; and this is the common prejudice against justification by the imputed righteousness of Christ received by faith alone, that it gives liberty to men to live loosely and sinfully, as though there was no room for good works in our religion, if they be not brought into our justification. But constant experience shows that this is a mistake; for they who embrace this doctrine are for good works as much as any, and dare not oppose the authority of that Spirit who, by the apostle James, pronounces that faith which is without good works to be dead. What we contend for is the right place, use, and end of good works in the matters of religion, that they may not be substituted in the stead of Christ, and the glory of our salvation be attributed to ourselves, against which the Scriptures so often caution us.”

After he had finished his academical studies, being 20 years of age, he returned to his parents, where he remained two years. He was then invited by Sir John Hartopp to reside in his family, at Stoke Newington, near London, as tutor to his son, where he remained five years.

He preached his first sermon on his birthday, 1698, and was the same year chosen assistant to Dr. Chauncey, pastor of the church then meeting in Mark Lane, London. In January, 1701-2, he received a call from the church to succeed Dr. Chauncey in the pastoral office, which he accepted the very day King William died, March 8th, 1701-2. Shortly afterwards, however, he was seized with an alarming illness, which rendered it necessary for the church to provide an assistant for him. As his health improved, he renewed his ministrations, but, in 1712, a violent fever so shook his constitution and nerves that debility attended him to his dying day.

The distressing state into which he was reduced roused in his friends a tender sympathy. Sir T. Abney took him into his house, at Abney Park, Stoke Newington, and supplied him with every comfort he could need or friendship could suggest. Sir Thomas died in 1722, but the same benevolent spirit actuated Lady Abney, who survived Watts above a year. He was once favored with a visit, at Lady Abney’s, from the Countess of Huntingdon, when he thus addressed her: “Madam, your ladyship is come to see me on a very remarkable day.” “Why is this day,” said she, “so remarkable?” “This day 30 years,” replied the doctor, “I came hither, to the house of my good friend, Sir Thomas Abney, intending to spend but one single week under his friendly roof; and I have extended my visit to exactly 30 years.” Lady Abney, who was present, immediately addressed the doctor: “Sir, what you term a long 30 years’ visit, I consider as the shortest visit my family ever received.”

During the whole of Watts’s sickness, the church insisted upon his receiving his salary, notwithstanding that he protested against it, as having no title to it, seeing that he never preached. How different was that to the conduct of some people, according to whose treatment, as a dear man, now in glory, once said, “God’s ministers ought to be either angels or asses; for if they were the former, when they had done preaching they could fly to their better country; and if the latter, the people could give them a kick, and turn them into the lane!”

During Watts’s residence at his father’s, after he left the academy, as already mentioned, he composed the greater part of his hymns. These were not published until 1707. He sold the copyright to a bookseller for .£10 only. A second edition was printed in 1709, corrected and much enlarged. His psalms were not printed till 1719. In 1728, the Universities both of Aberdeen and Edinburgh conferred upon him the degree of D.D.

I have mentioned that, through a fever in 1712, Watts’s nerves were greatly shaken. Many strange stories are told respecting his nervousness and imagination, which, if true, would imply that he was really, at times, out of his mind; such as, for instance, his imagining that, though he was really only five feet high, he was too big to enter the pulpit or go through a doorway. Dr. Gibbons, however, positively denies these stories, from his own personal knowledge. Watts’s life was a life of study, and, consequently, very few interesting circumstances are connected with it. He was once in the coffee-room of an hotel, when he overheard one person ask another, “Is that the great Dr. Watts?” Upon which Dr. Watts turned suddenly round and repeated the following from his Lyric Poems:

“Were I so tall to reach the pole,

Or mete the ocean with my span,

I must be measured by my soul,

The mind’s the standard of the man.”

The following is recorded upon such unquestionable authority that its authenticity cannot reasonably be doubted. A person in Southampton, who was a stone-mason, and who had purchased an old building for the materials, previous to his pulling it down came to Mr. Watts, under some uneasiness, in consequence of a dream, viz., that a large stone in the centre of an arch fell upon him, and killed him. Upon asking Mr. Watts his opinion, he answered him to this effect: “I am not for paying any great regard to dreams, nor yet for utterly slighting them. If there is such a stone in the building as you saw in your dream (which he told him there really was), my advice to you is, that you take great care, in taking down the building, to keep far enough off from it.” The mason resolved that he would; but in an unfortunate moment he forgot his dream, went too near this stone, and it actually fell upon him, and crushed him to death.

Watts was several years distressed with continual wakefulness, so that sometimes even opiates lost their effect upon him. Very little is said of his last days. About half an hour before he died, Whitefield called upon him, and, asking him how he was, he replied, “Here I am, one of the Christ’s waiting servants.” Some medicine was just then brought in, and Whitefield helped him up until he took it; upon which Dr. W. apologised for the trouble he gave him. “Why, surely, my dear brother,” said Whitefield, “I am not too good to wait upon one of Christ’s waiting servants!” Watts often expressed that he had not the shadow of a doubt as to his future happiness, and said, “I bless God I can lie clown with comfort, not being solicitous whether I awake in this world or another.” Again,”I should be glad to read more, yet not in order to be confirmed more in the truth of the Christian religion, or in the truth of its promises, for I believe the men ought to venture an eternity on them.” When he was almost worn out and broken down by his infirmities, he observed in conversation with a friend, that he remembered an aged minister used to say, that the most learned and knowing Christians, when they come to die, have only the same plain promises of the gospel for their support, as the common and unlearned “and so,” said he, “I find it.” He told a friend, in answer to his inquiry if he felt any pain, that he did not, and said it was “a great mercy;” and he gave the like answer when asked about his soul, and said he experienced the comfort of those words, “I will never leave thee nor forsake thee.” He expired the next day, Nov. 25th, 1748, and was buried in Bunhill Fields. Whitefield said of him, that for years together he might be said rather to gasp than to live.

2. Josiah Miller, “Our Hymns: Their Authors And Origin”

This most popular of English hymn-writers was the son of a respectable schoolmaster at Southampton, and the eldest of eight children. He was born July 17, 1674. His parents were eminently pious, and suffered much in the persecution duringCharles II’s reign, his father being more than once imprisoned for his nonconformity. In a book MSS., headed “Memorable Affairs in my Life,” there is this note:—“1683, My father persecuted and imprisoned for nonconformity six months. After that forced to leave his family, and live privately for two years.” Isaac was a precocious child, and made such progress in his classical studies under the care of a clergyman, the Rev. Mr. Pinhorne, at that time rector of All Saints, Southampton, as to awaken the delight and expectation of his friends. At the age of sixteen, he declined a proposition to support him at the university, and declared his resolution of taking his lot with the Dissenters. He went to London to study in the academy of the Rev. Thomas Rowe, an Independent ministry. “Such he was,” says Dr. Johnson, “as every Christian church would rejoice too have adopted.” There he made progress in his studies, and became decided in his Christian character. At the age of nineteen, he joined the church then meeting at Girdlers Hall, under the pas toral care of his tutor. To both these preceptors Watts has inscribed odes in his “Horae Lyricae.” During his stay in London, the young student injured his constitution for life by excessive study. Leaving London for a time, Watts returned, at the age of twenty, to his father’s house, to spend two years in more extended preparatory studies. During this time he wrote many of his hymns, and continued the poetic pursuits he had begun in his boyhood. Having complained to his father of the compositions ordinarily used by the congregation with which they worshipped at Southampton, his father, who was a deacon of the church and a man of taste, suggested that he should try his hand, and these hymns were the result. The first composed is said to have been—“Behold the glories of the Lamb”—(No. 303) in the “New Congregational Hymn Book,” where it is given with the omission of two verses.

From 1696 to 1702 Watts resided with Sir John Hartopp, Bart., at Stoke Newington, in order to be tutor to his son. This was a most valuable seedtime for future harvests, and Watts gladly prolonged his stay after he had commenced his pastoral work. Sir John was a staunch Nonconformist, and heavy fines were inflicted on him because of his adherence to his principles. He was also a man of deep sympathy with almost every department of literature and science. Hence, Watts could learn while he taught. And though incomparative seclusion, his knowledge was expanded and his principles were firmly grounded so as to fit him for the public duties of his long and active life. It was during this period that he formed the outline of his work on “Logic.”

Watts began to preach on his birthday, 1698, and was chosen the same year as assistant minister to the Rev. Dr. Isaac Chauncy, pastor of the Independent Church, Berry-street, London. His services were acceptable, but they were interrupted by illness. In 1702, he succeeded Dr. Chauncy in the pastoral office, notwithstanding the discouragement to Nonconformists, arising from the death of King William, which happened at that time. But subsequently Watts s uncertain health made it necessary to associate with him an assistant minister. The appointment fell on the Rev. Samuel Price, who some years later became co-pastor with him, and with whom Watts spent, as he says, “many harmonious years of fellowship in the work of the Gospel.”

In 1712, Watts went to visit Sir Thomas Abney, at his seat at Theobalds, in Hertfordshire. By the request of his kind entertainer this visit became a permanent residence; and for the remainder of his life thirty-six years the poet preacher found with Sir Thomas, and afterwards with Lady Abney, a rural home just suited to his delicate state of health, and very favourable for the prosecution of his laborious literary pursuits. Sir Thomas had been knighted by King William, and was Lord Mayor in 1700. He had been brought up as a Dissenter, and married a daughter of the celebrated Caryl. Watts not only found at Theobalds a congenial place of residence, but had also there the advantage of being within an easy distance of his congregation, to whom he preached as often as ids health permitted. His attacks of illness were very severe, and from 1712 to 1710 he was obliged to desist altogether from his ministerial work.

Watts collected works were first published by him in 1720, in six quarto volumes. They consist for the most part of sermons (to some of which suitable hymns are appended), and treatises on great theological subjects; and while comprehensive and scholarly in their character, and in some places marked by the boldness of their speculations, they are notwithstanding of a very practical nature.

Southey, in his life of Watts, has pointed out that the poet acknowledges that in his later years his speculations were content with a lower flight. For in a note appended to his sermons on the Trinity, which were published years after they were written, Watts were “warmer efforts of than says they imagination riper years could indulge on a theme so sublime and abstruse.” And he adds, “Since I have searched more studiously mystery of life, I have learned more of my own ignorance; so that when I speak of these unsearchables, I abate much of my younger assurance, nor do my later thoughts venture so far into the particular modes of explaining the sacred distinctions in the Godhead.”

His sole aim in his prose works, as in his psalms and hymns, was Christian usefulness. In addition to his theological treatises His works include that already mentioned on “Logic.” This had reached a seventh edition in 1740; one on “Astronomy;” one on the “Improvement of the Mind;” his “Art of Reading and Writing English;” an “Essay to Encourage Charity Schools;” a “Guide to Prayer” (1716), containing the substance of what he had addressed to the younger members of his church in a society for prayer and religious conference he formed for their benefit (sixth edition, 1735); his “Improvement of the Mind” (second edition, 1748); his “World to Come” (second edition, 1745); his “Humble Attempt towards the Revival of Religion” (third edition, 1742), and some others.

Dr. Watts did not claim to be a poet. He says: “I make no pretenses to the name of a poet, or a polite writer, in an age wherein so many superior souls shine in their works through the nation.” He did not produce any great poetic work, yet he thought it wise to publish his “Lyric Poems” as his introduction to the public before he ventured on the publication of his hymns. His work “Horae Lyricae” was sent forth in December, 1705. In his MSS we read, “Published my Poems, 1705.” In it there are several imitations of a modern Latin poet, Matthias Casimir (Sarbiewski), who was a favorite with the young poet. To his own copy of that poet’s works, which he purchased in 1696, Watts has prefixed an index in his own handwritings. M. C. Sarbiewski (1595-1640) was a learned and talented Pole. He had become a Jesuit, and was a professor and preacher in high repute. He was an enthusiastic admirer and imitator of the classics. Dr. Watts, in his preface to the “Lyrics,” speaks of his poems in the most glowing terms. This undesirable model rather encouraged than checked Watts’ early defects of style. But some of the “Lyrics” are to be commended, and some make good hymns, and are found in the “New Congregational Hymn Book.” His “Lyrics” met with favor, and prepared the way for his “Hymns,” which appeared in July, 1707. We give the date from his own memoranda. And, in 1709, their number was increased by the publication of addition hymns in the second edition.

It is as a writer of psalms and hymns that Dr. Watts is known everywhere, and justly held in high admiration. Some of his hymns were written to be sung after his sermons, the hymn in each case giving expression to the meaning of the text upon which he had been discoursing. Produced as they were wanted, and for a practical purpose, some of these hymns lack the fire and genius of poetry, and the same must be admitted of some of his other productions. He apologizes for the absence of poetic form and display on the ground of his desire to write to the level of ordinary worshippers, and says he expected to be often censured for a too religious observance of the words of scripture, whereby the verse is weakened and debased according to the judgment of critics,” yet all will admit that many of his hymns are of unparalleled excellence. Montgomery justly styles Watts “the greatest name among hymn-writers.”

To Dr. Watts must be assigned the praise of beginning in our language a class of productions which have taken a decided hold upon the universal religious mind. On this account, Christian worshippers of every denomination and of every English speaking land owe him an incalculable debt of gratitude. Mason, Baxter, and others, had preceded Watts as hymn-writers, but their hymns were not used in public worship. Prejudice prevented the use of anything beyond the Psalms, and those not yet in their Christian rendering. But Watts made the Christian hymn part of modern public worship. “He was,” says Montgomery, “almost the inventor of hymns in our language, so greatly did he improve upon his few almost forgotten predecessors in the composition of sacred song.” His aim was usefulness in public worship. He says, “The most frequent tempers and changes of our spirit, and t conditions of our life, are here copied, and the breathings of our piety expressed according to the variety of our passions, our love, our fear, our hope, our desire, our sorrow, our wonder, and our joy, as they are refined into devotion, and act under the influence and conduct of the blessed Spirit, all conversing with God the Father by the new and living way of access to the throne, even the person and the mediation of our Lord Jesus Christ. To Him also, even to the Lamb that was slain and now lives, I have addressed many a song, for thus doth the holy Scripture instruct and teach us to worship in the various short patterns of Christian psalmody described in the Revelation. I have avoided the more obscure and controverted points of Christianity, that we might all obey the direction of the Word of God, and sing His praises with understanding (Psalm 47:7). The contentions and distinguishing words of sects and parties are excluded, that whole assemblies might assist at the harmony, and different churches join in the same worship without offence.”

That Watts is in some cases tame and prosaic; that his rhymes are sometimes poor, and sometimes omitted where they are needed; that his expressions are sometimes unguarded and objectionable; that his doctrines are sometimes drawn rather from system than from scripture; and that he has not always escaped the defects that disfigure the early Latin Christian hymns must be admitted with regret. Yet Watts must always stand high for the comprehensiveness and catholicity of his hymns, for their fulness of gospel doctrine; and for the numerous instances in which they fulfil all that can be required in a Christian hymn, and in which criticism is forgotten in the joyful consent of the Christian reader s heart.

In his Preface to his Psalms, and in his “Essay towards the Improvement of Psalmody,” he has explained the special service he rendered in producing a Christian version of the Psalms. He gives it as his view that the Psalms “ought to be translated in such a manner as we have reason to believe David would have composed them if her had lived in our day.” And it contrast with the practice of his predecessors, he says, “What need is there that I should wrap up the shining honors of my Redeemer in the dark and shadowy language of a religion that is now for ever abolished; especially when Christians are so vehemently warned, in the epistles of St. Paul, against a Judaizing spirit in their worship as well as doctrine?” And of his own work, he says, “I think I may assume this pleasure of being the first who hath brought down the royal author unto the common affairs of the Christian life, and led the Psalmist of Israel into the church of Christ, without anything of a Jew about him.” Hence the author of the “Poet of the Sanctuary” justly says, “Whatever Dr. Watts might borrow from his predecessors, he stands alone as the evangelical psalmist.” Dr. Watts carried out his design by omitting whatever was so peculiar to David, whether person ally or in his official capacity, as to render it unfit for congregational use. He also left out whatever was unsuitable to the advanced dispensation under which we live, and either omitted names of persons and places that are now little known, or substituted known names and persons for them. And where prophecy has become history, he spoke of it as such. In the quarto edition of his works notes, between the Psalms, with references to New Testament passages, explain how he has carried out his design. This design was carried out in the face of some opposition. Romaine and Adam Clarke condemned Watts for thinking he could improve on the Psalms of David. The full title of the work was, “The Psalms of David, imitated in the language of the New Testament, and applied to the Christian state and worship,” 1719. In his preface, he acknowledges that he was occasionally indebted to the labours of his predecessors in the same work, Sir John Denham, Mr. Milbourn, Mr. Tate, Dr. Brady, and Dr. John Patrick, and says that to the last-mentioned writer he owes the most. Dr. Watts laboured at his Psalter from 1712 to 1716, during his cessation from public duties in consequence of illness. The complete work was published in 1719, after the sixth edition of the hymns, and met with a very ready sale.

Dr. Watts was beloved and useful as a Christian pastor and preacher, and his written works had an extensive circulation. In addition to those already spoken of as actually published, he sketched out the plan of the “Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul.” But growing infirmities having prevented him from writing it, he handed the work over to Dr. Doddridge, took deep interest in its progress, and expressed his approval of the manner of its execution. In a letter, bearing date Sept. 13, 1744, four years before his death, he says: “I wish my health had been so far established that I could have read over every line with the attention it merits, but I am not ashamed by what I have read to recommend it as the best treatise on practical religion which is to ba found in our language.” Dr. Watts never married, but he was very fond of children, and proved himself their friend by writing many simple books for them. His far-famed “catechisms” and “Divine Songs” were written at the request of Sir Thomas and Lady Abney, and evince the adaptive power of the writer, who could teach alike young or old, in poetry or prose, by the pulpit or the press. Dr. Watts received his Doctor s degree in 1728, from the Universities of Edinburgh and Aberdeen, both of which had, without his knowledge, conferred it upon him with every mark of respect.

As we might judge from his hymns, Dr. Watts Christian character was of the highest order. His humility and generosity were particularly conspicuous. During thirty-six years, he constantly devoted a fixed part of his income to charitable purposes; and he was not less noted for his liberality of sentiment towards Christians of other denominations, with many of whom he enjoyed Christian friendship. Nor is it necessary to say how zealous he was for the truths of the Gospel and for the cause of Christ, since this shines out in all his productions.

Dr. Johnson, the celebrated lexicographer, will not be suspected of partiality to a Dissenter, yet he gives in his “Lives of the Poets” the following high yet just estimate of Dr. Watts. “Few men,” he says, “have left behind such purity of character, or such monuments of laborious piety. He has provided instruction for all ages, from those who are lisping their first lessons, to the enlightened readers of Malebranche and Locke; he has left neither corporeal nor spiritual nature unexamined; he has taught the art of reasoning, and the science of the stars. His character, therefore, must be formed from the multiplicity and diversity of his attainments, rather than from any single performance; for it would not be safe to claim for him the highest rank in any single denomination of literary dignity; yet perhaps there was nothing in which he would not have excelled, if he had not divided his powers to different pursuits.”

For his own sake we must regret the weakness and suffering of Dr. Watts’ life; yet since thereby opportunities for retirement and composition were afforded him, and his deep experiences became the riches of the church, we cannot but recognise therein the wisdom and goodness of a superintending Providence. When the venerable poet, at the age of seventy-five, approached his end, he expressed himself as “waiting God’s leave to die,” and thus he entered into his rest. Dr. Watts died Nov. 25, 1748, at the residence of Lady Abney, who survived him, at Stroke Newington, where he had resided many years.

In a letter, dated Stoke Newington, Nov. 24, 1748, Mr. Parker sends Dr. Doddridge the following words, as just noted down from Dr. Watts dying lips. The dying divine said: “I would be waiting to see what God will do with me; it is good to say as Mr. Baxter, what, when, and where God pleases. The business of a Christian is to do and hear the will of God, and if I was in health I could but be doing that, and that I may be now. If God should raise me up again, I may finish some more of my papers, or God can make use of me to save a soul, and that will be worth living for. If God has no more service for me to do, through grace, I am ready. It is a great mercy to me that I have no manner of fear or dread of death; I could, if God please, lay my head back and die without alarm this afternoon or night.” At another time, he said, “My chief supports are from my view of eternal things, and the interest I have in them; I trust all my sins are pardoned through the blood of Christ.”

Dr. Watts’ evangelical psalms and hymns are believed to have done much during the eighteenth century to preserve the Congregational Churches from the frigid formalism of those times. And now, having found their way into Episcopalian, Wesleyan, and other collections, they are carrying on their Gospel mission in many communities and in many lands.

From among many who have expressed their indebtedness to Dr. Watts, we select that celebrated convert to Christ, Colonel Gardiner, whose testimony is strong and decided. In a letter to Dr. Doddridge, he expresses his fear lest the poet should die before he had an opportunity of thanking him, a fear not ful filled, as Dr. Watts lived to acknowledge Dr. Doddridge s letter conveying the thanks. The pious Colonel writes: “Well am I acquainted with his works, especially with his Psalms, Hymns, and Lyrics. How often, by singing some of them when by my self, on horseback, and elsewhere, has the evil spirit been made to fly away.

“Whene’er my heart in tune was found,

Like David’s harp of solemn sound.”

3. Hezekiah Butterworth, “The Story Of The Hymns”

The bicentennial of Dr. Watts has just been observed in England, and, among all the contributors to modern psalmody, no one has left a clearer and purer tone in the church. The calm, unsullied light of his fame is not dimmed; his name holds a steady place as a benefactor, and his best thoughts, like ministering angels, still traverse every portion of the Christian world on the multitudinous wings of song. His tomb in the unconsecrated dust in Bunhill Fields still invites the grateful steps of the traveller, and his effigy in Westminster Abbey commands a larger respect than the busts of kings. Few men’s thoughts have so lived in the thoughts ot others as have those of Dr. Watts.

The father of Dr. Watts was a deacon of the Independent church at Southampton. At the age of eighteen Isaac complained of the want of taste in the hymns then generally used, and was requested to produce something better. He accordingly wrote an original hymn for the close of a Sabbath service in Southampton. It was given out in the usual manner, by the clerk, and greatly pleased the worshippers. It was the hymn, beginning, “Behold the dories of the Lamb.”

He was invited to write other hymns for use in the same church, and soon produced a sufficient number to make a book. The book met a demand of the times, and was immediately popular.

Among his early hymns was one composed under very interesting circumstances. Dr. Watts was enamored of Miss Elizabeth Singer, afterwards the celebrated Mrs. Rowe, who was greatly admired for her personal beauty, intellectual graces, and moral excellences. Some of the most accomplished men of the time were among her friends, and several offered her their hands.

Dr. Watts proposed marriage to Miss Singer, and was rejected. He was small in stature and lacking in personal beauty. Miss Singer, in alluding to his intellectual worth, said that she “loved the jewel, but could not admire the casket that contained it.” His disappointment was very great, and in the first shadow of it he thus exhibits the feelings of his heart:

“How vain are all things here below,

How false, and yet how fair;

Each pleasure hath its poison too,

And every sweet a snare.

The brightest things below the sky,

Give but a flattering light;

We should suspect some danger nigh,

Where we possess delight.

Our dearest joys and nearest friends,

The partners of our blood,

How they divide our wavering minds,

And leave but half for God.

The fondness of a creature’s love,

How strong it strikes the sense;

Thither the warm affections move,

Nor can we call them thence.

My Saviour, let thy beauties be,

My soul’s eternal food;

And grace command my heart away,

From all created good.

The hymn, beginning, “There is a land of pure delight,” associates itself with the natural scenery of Southampton, his native town. It was written while he was sitting at the window of a parlor, overlooking the river Itchen, and in full view of the Isle of Wight. The landscape there is very beautiful, and forms a model for a poet to employ in describing allegorically the passage of the soul from earth to the paradise above.

Watts lived a tranquil, uneventful life, passing thirty-four years in the seclusion of Alney Park, a nobleman’s seat, where he had been invited to make a home. His health was always delicate. He both preached and wrote, but his best efforts were given to his pen.

A critical writer in the “Oxford Essays”‘ fixes upon the hymn beginning, “When I survey the wondrous cross,” as Dr. Watts’ best original effort; and pronounces the rendering of the ninetieth Psalm, beginning, “Our God, our help in ages past,” as his finest paraphrase. The latter indeed not only preserves the sublime and lofty spirit, but the grand and shadowy imagery of the Hebrew lawgiver’s poetical contemplation:

“A thousand ages in thy sight,

Are like an evening gone;

Short as the watch that ends the night,

Before the rising sun.

Time, like an ever-rolling stream,

Bears all its sons away;

They fly, forgotten, as a dream,

Dies at the opening day.

The busy tribes of flesh and blood,

With all their cares and fears,

Are carried downward by the flood,

And lost in following years.”

4. Frederick John Gillman, “The Story Of Our Hymns”

Watts is the real founder of modern English hymnody. The two streams of song which at the Reformation flowed from Luther to Calvin—the “human hymns”conveying and enforcing Christian truth, and the paraphrases founded upon the Psalms, unite in his writings.

He was the son of a schoolmaster of Southampton who, among a large company of nonconformists, suffered persecution at the hands of the Stuarts. Many times the elder Watts was imprisoned in Southampton jail, and there his wife was frequently to be seen, sitting patiently outside the gates, with her infant son Isaac in her arms. In his boyhood Isaac was often entrusted with the care of his younger brothers and sisters, and there may well be a touch of autobiography in his “Moral Songs for Children,” including as they do “Let dogs delight to bark and bite,” and “How doth the little, busy bee.” The mother encouraged her young children to write verses by offering them prizes of farthings: but little Isaac, conscious of the gift that was in him, declined to take the prize, and handed his mother this couplet by way of explanation:

“I write not for a farthing, but to try,

How I your farthing writers can outvie.”

Young Watts attended the Congregational Chapel with his parents, and one day complained to his father of the inadequacy of the paraphrases to meet the spiritual needs of the congregation; and his father challenging him to provide something better, he wrote his first hymn, which began significantly with the words:

“Behold the glories of the Lamb,

Before His Father’s throne;

Prepare new honours for His name,

And songs before unknown.”

Though all unknown to the writer, this simple incident was in reality epoch-making. It marked the commencement of a new era it was the first note of a new song that will never cease.

Not only did the inadequacy of the paraphrases impress Watts, but also the indifference and deadness of spirit with which they were sing. In his preface to his collected hymns he says, “When we sing the praises of our God in His Church, we are employed in that part of Worship which of all others is the nearest akin to Heaven; and tis pity that this of all others should be performed the worst upon earth.”

By his series of hymns and by his paraphrases (which he converted into Evangelical songs, “making David speak like a Christian”) he revolutionized the worship-song of the Congregational Churches and ultimately of the whole nation. His best paraphrases are of great vigour and beauty, as will be seen from our No. 108 “Praise ye the Lord” and No. 131 “O God, our help in ages past,” the latter of which has become a classic and stands supreme with the Te Deum as a fitting vehicle for a nation’s emotions at the great epochs in its history.

5. Edwin Long, “Illustrated History Of Hymns And Their Authors”

Watts, the author of many of the hymns contained in the Church hymn books of our day, was born in Southampton, England, on the 17th of July, 1674.

His father kept a flourishing boarding-school in that town, which was held in such high repute that students were sent to it from America and the West Indies. He was an earnest Christian, a deacon of the Independent or Congregational church. Soon after the birth of Isaac, their first born child, the father was imprisoned in the South-Castle Jail, because of his non-conformity.

The mother, in her affliction, is said to have often seated herself on a stone near the prison door, with the poet, then an infant “suckling at her breast,” and at times, to have “lifted him up to the cell window to comfort the father in bonds.”

His precocious intellect soon began to show itself. Before he could speak plainly, when money was given him he would say, “A book! a book! buy a book.”

In his fourth year he began the study of Latin; in his ninth, the study of Greek; in his tenth, the study of French; and in his thirteenth, the study of Hebrew.

During the play-hours in his father’s school, his mother promised a copper-medal to those of the pupils who would construct the best verses, when little Isaac, but some seven years of age produced the couplet:

“I write not for your farthing, but to try

How I your farthing-writers can outvie. “

His piety was very early manifested. Well could he adopt the beautiful language of Mrs. Rowe:—“My infant hands were early lifted up to Thee, and I soon learned to know and acknowledge the God of my fathers.”

In 1698, on his birthday, when just twenty-four years of age, he preached his first sermon, and in the same year was chosen assistant pastor of the Independent Church, Mark Lane, London, and in 1702, became its sole pastor. On account of his feeble health his people provided him with an assistant, the Rev. Samuel Price. Though an invalid, Dr. Watts served his church for nearly fifty years. Often his exertions in the pulpit were followed by such weakness and pain that he was obliged to retire immediately to bed and have his room closed in darkness and silence.

Invited by Sir Thomas Abney in 1712 to visit his mansion at Theobalds, for a change of air, he gladly complied. It became his home for the rest of his life.

Abney House, Where Watts Lived And Died

A lady calling to see him one day, Dr. Watts said: “Madam, your ladyship is come to see me on a very remarkable day. This very day, thirty years ago, I came to the house of my good friend, Sir Thomas Abney, intending to spend but one single week under his friendly roof, and I have extended my visit to his family to the length of exactly thirty years.”

Lady Abney, who was present, immediately replied, “Sir, what you term a long thirty years’ visit, I consider the shortest my family has ever received.”

Soon after he had a dangerous illness, from which, after a long confinement, he but slowly recovered.

Dr. Gibbons says: “Here he dwelt in a family, which, for piety, order, harmony, and every virtue, was a house of God. Here he had the privilege of a country recess, the fragrant bower, the spreading lawn, the flowery garden, and other advantages to soothe his mind, and aid his restoration to health; to yield him, whenever he chose them, most grateful intervals from his laborious studies, and to return to them with redoubled vigor and delight.”

His physical frame is thus described by his biographer: “He measured only about five feet in height, and was of a slender form. His complexion was pale and fair, his eyes small and gray, but when animated, became piercing and expressive; his forehead was low, his cheek bones rather prominent; but his countenance was, on the whole, by no means disagreeable. His voice was pleasant, but weak. A stranger would, probably have been most attracted by his piercing eye, whose very glance was able to command attention and awe.”

Being at a hotel with some friends, some one made the remark, rather contemptuously,— “What! is that the great Dr. Watts?” As this was unexpectedly over-heard by Dr. Watts, he at once replied, as he turned towards the critic, and said:—

“Were I so tall to reach the pole,

Or grasp the ocean with my span,

I must be measured by my soul,

The mind’s the standard of the man.”

The apt reply is said to have produced silent admiration for the “great” little man.

Dr. Gibbons speaks thus of his mental greatness:—”Perhaps very few of the descendents of Adam have made nearer approaches to angels in intellectual powers and divine dispositions than Dr. Watts; and among the numerous stars which have adorned the hemisphere of the Christian Church he has shone and will shine an orb of the first magnitude.”

Dr. Johnson, the eminent lexicographer, gives the following estimate of his capacity:—“Few men,” says he, “have left behind such purity of character, or such monuments of laborious piety. He has provided instruction for all ages,—from those who are lisping their first lessons to the enlightened readers of Malebranche and Locke.”

“Not Jordan’s stream, nor death’s cold flood,

Should fright us from the shore.”

This language was typical of the experience of its author. It is said of Watts, “Calmly and peacefully did his weary, longing spirit leave its feeble earthly tenement and wing its way to God.”

Often would he say, “I bless God I can lie down with comfort at night, not being solicitous whether I wake in this world or another.” Before his departure, he said: “It is good to say as Mr. Baxter, ‘What, when, and where God pleases.’ If God should raise me up again I may finish some more of my papers, or God can make use of me to save a soul, and that will be worth living for It is a great mercy to me that I have no manner of fear or dread of death: I could if God please, lay my head back and die without ‘terror, this afternoon or night.’”

Being “worn out by infirmities and labor,” rather than by any particular disease, he simply ceased to breathe on the 25th of November, 1748, in the 75th year of his age. In accordance with his catholic spirit, and his expressed wish, his body was conveyed to its resting-place by pall-bearers that consisted of two ministers from each of the three denominations. The following description of his monument is given in the Sabbath at Home:

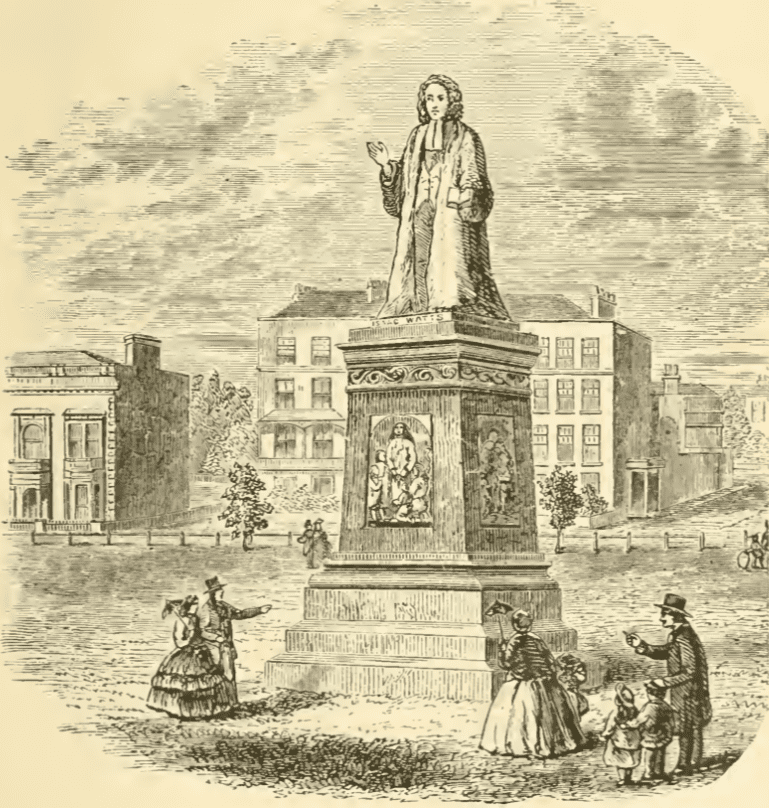

A MONUMENT in honor of Dr. Watts was erected some years ago in the town of his birth. It was the product of public subscription. On the inauguration-day, an address was delivered by the Earl of Shaftesbury; and the memorial was afterward formally delivered over to the mayor and corporation of Southampton. The monument, sculptured by Mr. R. T. Lucas, stands in the Western Park. It has an entire height of nineteen feet, with a base eight and a half feet square. The statue represents the minister of religion addressing his congregation, and is of the purest white Sicilian marble, about eight feet high, facing the south. It surmounts a pedestal of fine polished gray Aberdeen granite, which has three marble basso-rilievos on the sides.

Monument Of Watts

One on the front represents the teacher instructing a beautiful group of children, under which is the motto,—“He gave to lisping infancy its earliest and purest lessons.”

The youthful poet is sculptured on the west side, with upturned glance; and underneath is his own descriptive line:—”To heaven I lift my waiting eyes.”

On the east side, Dr. Watts is depicted as a philosopher with globe, telescope, hour-glass, and Dr. Johnson’s delineation of him:—“”He taught the art of reasoning and the science of the stars.”

On the north side is a marble tablet, with an inscription witten by John Bullar, Esq:—“A. D. 1861. Erected by Voluntary Subscriptions, In memory of Isaac Watts, D. D., A native of Southampton. Born 1674; died 1748.”

6. Ken Connolly, “The Church In Transition”

Isaac Watts was born in the city of Southampton in 1674. His paternal grandfather was a renowned British Naval Commander who is reputed to have drowned a tiger in a jungle river when it attacked him . His maternal grandfather was a French Protestant who fled to England to escape persecution. Isaac Watts’ father was a deacon in the local Congregational church. The elder Watts suffered in prison many times for his outspoken manner on the subject of religious freedom. When Isaac was a child, he frequently sat on a particular stone just outside the jail window while his parents conversed through the prison bars.

By the time Isaac Watts was eight years of age, he had mastered both Greek and Hebrew. Even at an earlier age he was displaying an ability to compose verse. When Isaac’s father heard him criticize the Psalms sung every Sunday, Mr. Watts angrily challenged him to compose better, if that were possible. Isaac immediately handed him a manuscript of verses based on Revelation 5:6-10. The father was sufficiently impressed to introduce his son’s work at the next Sunday morning service. There the congregation was so impressed that they asked young Isaac to compose another one for the following Sunday. That he did for two hundred twenty two consecutive Sundays!

Sometime later, Isaac’s older brother, Enoch, wrote him a letter and reminded him of the several requests for him to put his hymns into print “for the common good.” Congregational churches in those days were averaging between three hundred fifty and four hundred people. They were autonomous congregations, and that made it easier to introduce new expressions in worship Slowly but surely, those hymns circulated and exerted influence on other congregations.

In 1702 Isaac Watts became the minister of the Independent Church of Mark Lane in London. In December of 1705 he printed his first volume of verses. It contained twenty-five of his hymns and four paraphrased Psalms. They were expressly presented for “lovers of poetry.” That allowed Watts to determine their acceptability. The first effort was apparently accepted because two years later he published his “Hymns and Spiritual Songs.” That book contained two hundred ten songs.

It should be remembered that those hymns contained many verses without choruses. The chorus was a later invention for the benefit of children who could not read. They could participate in every song by just memorizing the chorus. Watts’ writings not only included the songs, but he provided the arguments which suggested that the Psalter was outdated. One without the other would have been abortive.

In 1715 Watts published another book of Divine Songs, and in 1719, he produced his classical work, “The Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament and Applied to the Christian State and Worship.” This work provided one song for each of the one hundred fifty Psalms.

After ten years in the pastorate, Isaac Watts’ health gave way and he suffered from a nervous breakdown. He was invited to recuperate at the London estate of the Lord Mayor and Lady Thomas Abney. Watts actually lived there for the rest of his life, 36 years.

There were twenty five years of his stay at the mayor’s residence in which he composed no hymns. He did, however, publish other material. Watts was a scholar, a man of letters, a philosopher, and a theologian. He received doctorates from the universities of Aberdeen and Edinburgh. He wrote on the Improvement of the Mind and Speculation on the Human Nature of the Logos. His book on Logic became a textbook at Oxford and was solicited by both Yale and Princeton in America.

Although he was only five feet tall, not overly handsome, and unmarried, Watts’ hymns went everywhere. After meeting George Whitefield, Watt resented what he considered the “excessiveness” of Whitefield, but later his attitude changed Whitefield took several volumes of Watts’ hymnbooks with him in 1738 when he made his first visit to America. In fact, a volume of Watts’ hymns lay by his Bible when Whitefield was found “absent from the body.” Though Watts was theologically opposed to the Wesley brothers when they published their first hymnal in 1737 (while engaged in missionary work in Georgia,) the hymns of Watts were frequently included among their own. Those hymns also crossed denominational barriers and were used in the hymnals first published by Baptists and Presbyterians.

Isaac Watts has truly been called the “Father of Modern Hymnology.” He died in 1748 at the age of seventy four. He is buried at Bunhill Fields.

Isaac Watts (1674 –1748) was an English Congregational preacher, theologian and hymn writer.

Isaac Watts Hymn Studies