Preface

The 1646 Westminster Confession Of Faith, Article 7, Paragraphs 2&3:

”The first covenant made with man was a covenant of works, wherein life was promised to Adam, and in him to his posterity, upon condition of perfect and personal obedience. Man by his fall having made himself incapable of life by that covenant, the Lord was pleased to make a second, commonly called the covenant of grace: wherein he freely offered unto sinners life and salvation by Jesus Christ, requiring of them faith in him that they may be saved, and promising to give unto all those that are ordained unto life his Holy Spirit, to make them willing and able to believe.”

The 1689 Second London Baptist Confession Of Faith, Article 7, Paragraph 1:

“Man having brought himself under the curse of the law by his fall, it pleased the Lord to make a covenant of grace, wherein He freely offers unto sinners life and salvation by Jesus Christ, requiring of them faith in Him, that they may be saved; and promising to give unto all those that are ordained unto eternal life, His Holy Spirit, to make them willing and able to believe.”

The language of the 1646 Confession is representative of the Presbyterian view of covenant theology, whereas that of the 1689 Confession represents the view of the Reformed Baptists. Both groups subscribe to a conditional covenant of grace, believing that God has made a covenant with sinners in time, requiring of them faith in Christ in order to be saved. This teaching sometimes goes by the name of Duty-Faith, and is often accompanied by the free offer of the gospel. It is on the basis of this conditional covenant that the foregoing groups have constructed their frameworks of covenant theology.

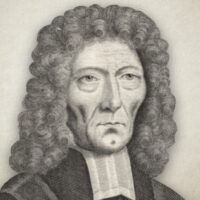

Benjamin Keach (1640-1704), one of the leading Strict and Particular Baptist pastors in London, endorsed the 1689 Confession, as his name appears with thirty-six other representatives “in the name of and on the behalf of the whole assembly”. However, three years later, he preached two sermons rejecting the notion of a conditional covenant of grace. In so doing, he destroyed the foundation upon which the Presbyterians and the Reformed Baptists have built their covenant theology.

The sermons were occasioned by the death of Henry Forty, the minister of a church in Abingdon. Keach chose for his text the dying testimony of King David, recorded in 2 Samuel 23:5: “[God] hath made with me an everlasting covenant, ordered in all things, and sure: for this is all my salvation, and all my desire.” Keach took the position that the everlasting covenant is one and the same with the covenant of redemption made by God from eternity on behalf of the elect, and that the scriptures do not support the idea that God has made an additional covenant of grace with sinners in time. He wrote:

“Question, Is not that Covenant which was made between the Father and the Son called the Covenant of Redemption, made from all Eternity a distinct Covenant from the Covenant of Grace? I Answer—…I must confess, I have formerly been inclined to believe the Covenant, or Holy Compact between the Father and the Son, was distinct from the Covenant of Grace; but upon farther search, by means of some great Errors sprang up among us, arising (as I conceive) from that Notion, I cannot see that they are Two distinct Covenants, but both one and the same glorious Covenant of Grace…Where do we read in all the Holy Scripture of Three Covenants, viz. 1. A Covenant of Works, 2. A Covenant of Redemption, 3. A Covenant of Grace: Evident it is to all, that the Holy Ghost only holds forth, or speaks but of Two Covenants, a Covenant of Works, and a Covenant of Grace [Redemption].”

Of course, anyone familiar with the development of covenant theology during the 17th and 18th centuries will know that John Gill (1697-1771), the successor to the church pastored by Keach, subscribed to the same view. In 1769, Gill published his “Body Of Doctrinal Divinity”, wherein he wrote:

“[The covenant of redemption] is the same with the covenant of grace; some divines, indeed, make them distinct covenants; the covenant of redemption, they say, was made with Christ in eternity; the covenant of grace with the elect, or with believers, in time: but this is very wrongly said; there is but one covenant of grace, and not two…What is called a covenant of redemption, is a covenant of grace…there can be no foundation for such a distinction between a covenant of redemption in eternity, and a covenant of grace in time.”

In 1828, Robert Hawker (1753–1827), an Anglican gospel preacher, published “The Poor Man’s Concordance And Dictionary To The Sacred Scriptures Both Of The Old And New Testament”. Under the heading, “Covenant”, he supplies a beautiful definition for the covenant of redemption (grace):

“The Scripture sense of this word is the same as in the circumstances of common life; namely, an agreement between parties. Thus Abraham and Abimelech entered into covenant at Beersheba. (Gen 21:32) And in like manner, David and Jonathan. (1 Sam 20:42) To the same amount, in point of explanation, must we accept what is related in Scripture of God’s covenant concerning redemption, made between the sacred persons of the GODHEAD, when the holy undivided Three in One engaged to, and with, each other, for the salvation of the church of God in Christ. This is that everlasting covenant which was entered into, and formed in the council of peace before the word began. For so the apostle was commissioned by the Holy Ghost, to inform the church concerning that eternal life which was given us, he saith, in Christ Jesus, “before the world began?” (Tit 1:2; 2 Tim 1:9) So that this everlasting covenant becomes the bottom and foundation in JEHOVAH’S appointment, and security of all grace and mercy for the church here, and of all glory and happiness hereafter, through the alone person, work, blood-shedding, and obedience of the Lord Jesus Christ. It is on this account that his church is chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world. (Eph 1:4) And from this appointment, before all worlds, result all the after mercies in time, by which the happy partakers of such unspeakable grace and mercy are regenerated, called, adopted, made willing in the day of God’s power, and are justified, sanctified, and, at length, fully glorified, to the praise of JEHOVAH’S grace, who hath made them accepted in the Beloved.

Such are the outlines of this blessed covenant. And which hath all properties contained in it to make it blessed. It is, therefore, very properly called in Scripture everlasting; for it is sure, unchangeable, and liable to no possibility of error or misapplication. Hence, the patriarch David, with his dying breath, amidst all the untoward circumstances which took place in himself and his family, took refuge and consolation in this: “Although (said he,) my house be not so with God, yet hath he made with me an everlasting covenant, ordered in all things, and sure; for this is all my salvation and all my desire, although he make it not to grow.” (2 Sam 23:5)

In the gospel, it is called the New Testament, or covenant, not in respect to any thing new in it or from any change or alteration in its substance or design, but from the promises of the great things engaged for in the Old Testament dispensation being now newly confirmed and finished. And as the glorious person by whom the whole conditions of the covenant on the part of man was to be performed, had now, according to the original settlements made in eternity, been manifested, and agreeably to the very period proposed, “in [what is called] the fulness of time, appeared to put away sin by the sacrifice of himself,” it was, therefore, called Covenant, in his blood. But the whole purport, plan, design and grace, originating as it did in the purposes of JEHOVAH from all eternity, had all the properties in it of an everlasting covenant; and Christ always, and from all eternity, “was considered the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world.” (Rev 13:8)”

It may be argued the “reformed” view of covenant theology, set forth in the 1646 and the 1689 Confessions, stood in need of further reform. This work fell to the gospel preachers of the 18th and 19th centuries, kickstarted by men such as Benjamin Keach. His two sermons on the subject are an important contribution to the development of covenant theology, which is why I add them to the online resources of the AHB. It is my prayer that this resource will encourage one, who like Keach, is on a journey of grace to nurture clearer views of Christ and to experience a greater measure of the sanctifying power of the Holy Spirit.

Jared Smith

Benjamin Keach (1640-1704) was a Particular Baptist pastor and prolific writer. He was converted to Christ in his youth and in 1659 began to preach the gospel under the auspices of a free will Baptist church in Buckinghamshire. In 1664, he was arrested on charges of publishing a schismatical catechism for children. He was sentenced to two weeks’ imprisonment, fined twenty pounds and pilloried for several hours in Aylesbury and Winslow. In 1668, he moved to London and was appointed the Pastor at the Horsleydown congregation in Southwark. Having now come into contact with several Particular Baptist ministers, he began to nurture Calvinistic views of the gospel, becoming one of the leading Particular Baptist ministers in London. He served thirty-six years as the Pastor for the Horsleydown church, was one of the signers of the 1689 Second London Baptist Confession of Faith and was the author of more than forty books.

Benjamin Keach on the Everlasting Covenant (Complete)