The Life And Ministry Of Joseph Tanner

Gospel Standard 1867:

Joseph Tanner, Of Cirencester

On Sunday afternoon, Feb. 10th, 1867, a few minutes before 4 o’clock, my beloved husband entered into rest.

For some little time before his last short but severe illness, he had been unusually better in health, and remarked to a dear friend, with whom he was walking from chapel on the last Sunday he ever left his home, how much better and stronger he felt; and his voice in preaching that day was observed to be particularly clear and full. He preached in the morning from Job 5:17, 18.

On Tuesday morning, Jan. 22nd, he was seized with his last fatal attack, commencing at first with every symptom of a severe cold and bilious sickness, accompanied by spasmodic pain; but he was able to sit up until evening, when his bed was warmed and he went to it, never more to rise. Having been for many years a constant sufferer, more or less, no apprehension of danger was immediately felt; but the sickness continuing with much cramp-like pain, we prevailed upon him to call in medical aid.

On the 24th his sufferings had greatly increased, and his vomitings had become most distressing. All our previous experiences in his similar alarming attack of 1862 availed us nothing in this illness. Every remedy and alleviation that had been tried with success then, we repeated now; but no blessing attended the means.

On Friday afternoon, he remarked, “It is all over; it is all over;” but, having seen him many times before in great extremity, and, according to our thoughts, much nearer death, we thought differently, and told him we quite hoped he would recover. He shook his head, as though he thought we were deceived.

On the Sunday evening he raised his voice for the last time in audible prayer with his family, in a very solemn and impressive manner, commending each beloved member unto the kind protecting care and keeping of his heavenly Father. He also entreated the Lord’s blessing upon the means used for his recovery, in these words: “O thou, who art alone the good Physician for body and soul, if consistent with thy holy will, command thy blessing, and say to this mountain of sickness, Depart! Nothing is too hard for thee.”

During the night, between the paroxysms of pain and sickness, he appeared much in prayer; but became so increasingly ill before morning that we called up our kind medical attendant, and in the evening of the day telegraphed for the physician whose skill and promptness, with the Lord’s blessing, we had found so valuable in his former dangerous seizure. After his visit and consultation, Dr. E. left us with a comfortable hope of my husband’s recovery, and pronounced him not to be so seriously ill as when previously summoned, in Sept., 1862. But, alas! It was a delusive hope that was raised in our hearts. God had designed to take him home to glory. The relief afforded by the new remedies prescribed was only temporary, and from Thursday morning, Jan. 31st, his sufferings became more and more excruciating, and he could speak very little, although greatly blessed in his soul, and favoured with the presence of the Lord. He said to me, “The Lord is crushing me to death with his mercy and goodness;” and he begged of me not to pray for his recovery, as he longed for the Lord to lift him out of his body of sin and suffering, quoting that verse of Medley’s:

“Weary of earth, myself, and sin,” &c.

I remarked, “The eternal God is your refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms.” He grasped my hand in his, and said, “Yes, yes; and you will meet me in glory. The lot has fallen to you in pleasant places, and you have a goodly heritage.” On one occasion, when speaking of the Lord’s goodness to us as a family, he said, “Our favourite hymn will hold good still:

“‘God moves in a mysterious way,'” &c.

His sufferings now were of so severe a nature that he could bear only a few words or short sentence at a time. Once, when looking very tenderly upon me as I sat by his side, he said, “Don’t weep, my dear; don’t weep. You can do better without me than I could do without you. In this my prayers will be answered. You are well cared for; you have beloved children. The Lord bless you; the Lord bless ‘you.” And then, raising his eyes upward, he added, “O why are his chariot wheels so long in coming?” At another time he broke out and sang, in a full voice, to the astonishment of those who heard him:

“How high a privilege ’tis to know,” &c.

He said, “Lord, now let thy servant depart in peace.” A friend, finding his weakness very great, finished the sentence: “for mine eyes have seen thy salvation.” He bowed his head.

On one occasion I remarked, “You find that sweet hymn, ‘Rock of Ages,’ precious still.” He answered, “Yes; no other shelter for my poor soul.” Once he drew me to him, and said, “God’s ways are not as our ways. He is teaching us by hard things, and causing us to drink the wine of astonishment; but it is well; it is all well. The Lord is good. O how good he has been to us, past all understanding.” At another time he remarked that his sufferings were very great, and none but the Lord and himself knew how great; and he expressed a fear lest he should be impatient, and asked forgiveness, if at any time he had been; but his patience astonished us. We never, to the best of our remembrance, heard a murmuring word during the whole of his severe suffering.

One time, when thinking of the little cause in Park Street, he said to me, “My dear, stick close to the truth;” and energetically exclaimed, “No compromise, no compromise in religion !”

On Monday, Feb. 4th, a kind and dear friend from a distance came to see him. He was then too weak to hold a conversation, but said, “I shall meet you in glory.” In the evening of the same day Dr. E. came again, and assured us there was hope still remaining, if we could only get him to take nourishment; but the sickness continuing, we found it quite impossible; and on his dear son entreating him to take something, he said, “Don’t trouble me. It is of no use. I am going home.” All he craved was ice and cold water; and frequently, when he took the glass, would repeat, “Water; God’s water; pure water.”

On Feb. 8th I observed a visible change in his countenance, an expression of marked dejection and distress, which made my heart ache. I inquired, “Are you not so well?” He opened his sad eyes, and, fixing them steadfastly upon me, said, “Death, death! And O if, after all, my lamp should go out, if my religion should not be right; no covering for my head! O how dark, how dark! A dying bed is a solemn place to be brought to. Nothing but realities will do now.” He was tried and exercised about his ministry, and solemnly appealed to us who wore in the room in these words: “Charge your consciences as, in the sight of God, have I ever dealt deceitfully with souls?” I said, “No; you have been a faithful witness for the truth, and. many among God’s dear people have borne testimony that you have been a faithful witness.” This dark cloud covered his soul for some hours. Two of the deacons coming in at this solemn time, and not being able to speak to him, they spoke one to the other. He opened his eyes and turned to me, as I sat by his bed, and said, in a pitiful tone, “Do they suspect my religion?” He was assured of the contrary. This was indeed a bitter hour. Some time after this I asked if he was happy. He said, “All is right. It is well. My feet are on safe ground. I have no ecstasy. A poor sinner saved by free and unmerited grace. This is a solemn hour.” His countenance depicted that what he said he felt. I said, “We cannot help you now.” “No,” he replied. “None but Jesus, none but Jesus. The valley of the shadow of death is a dark place, and we must each go through it. You must die for yourself. You will have your own conflict.” And he then repeated:

“In that dread moment,

O to hide Beneath his shelt’ring blood,

‘Twill Jordan’s icy waves divide,

And land my soul with God.”

On Sunday, between the hours of 12 and 1 o’clock, every member of his family, with the exception of a son who was abroad, assembled in his room, and took a separate and last farewell, each receiving a father’s dying blessing. Two of the deacons came in, and one of them, at the request of my husband, engaged in audible prayer by his bed. At the end, my husband said, “Amen! Amen!” This was truly a solemn scene, which will not be soon forgotten. He said to one of the deacons, “Give my love to all, to all,” repeating the words as though not one should be left out; and he then said, “It is well; it is well.”

In a short time after this, all pain and distress appeared to leave him, and in peace and tranquillity of soul, like a little child in the fond embrace of a tender mother, he gently sighed his soul away unto everlasting bliss.

The Lord grant, for his mercy’s sake, that I may die the death of the righteous, and that my last end may be like his.

He was perfectly sensible up to the last moments of his life, and was so during his illness, his head not being at all affected. His dear son was the one who caught his last words. He was supporting his dying body when he tried to repeat that verse of Hart’s:

“This pearl of price no works can claim;”

but the words died on his lips. After a few seconds he said, “I leave this world of woe and strife. Blessed Jesus! Blessed Jesus!” which were the last he ever spoke.

I look back and see that the Lord was preparing my husband for some time for the happy change. He had been conversant with death for several years past; but the last twelve months more especially. He would frequently say death was not far off, and many times I have heard him say how glad he should be if lie were undressing for the last time; and at the end of the Sabbath, how he longed to be where there would be no Monday morning. During the last few months of his life, I have often witnessed that the manifold mercies and favours of God to him and his family have been more than he could bear; and when sitting down to partake of God’s bounties, words of gratitude and thankfulness would burst forth: “What mercies! What comforts! What indulgences!”

He was often much cast down on account of the ministry, and especially at Cirencester, and has many times within the last twelve months said, “I think my work in this place is nearly done; and I sometimes feel, when coming out of the pulpit, as though I could wish it were the last time. I seem to be of no use here. I want to know the mind of the Lord, whether or not I am to go out more, or what he is about to do with me. God knows I would not move without his bidding if I knew it.”

March 5th, 1867

Mary Tanner

[In the course of a long profession I have had the pleasure, and I hope I may say profit, of personally knowing many godly men, both in the ministry and out of it; and I have had to lament year by year the loss of many dear and esteemed friends, whom the Lord has taken one after another unto himself. Among these I shall ever reckon Mr. Joseph Tanner, the subject of the above Obituary; for I do not know a better word by which to describe him than that which I have already used, a godly man. I did not indeed know him at all intimately until the autumn of 1860, when, having gone to Girencester to fulfil an engagement to preach there, it pleased the Lord to lay upon me an attack of illness which confined me to the house for about three weeks, during the whole of which time I was his guest; and I am sure nothing could exceed the affectionate kindness and attention which I received during that time from both himself and every member of his family. It was then, however, for the first time that I might be said really to know him, for his natural shyness of disposition, and the low views which he had of himself as a Christian and as a minister had much kept him back before from seeking my personal acquaintance. But during those three weeks we had at times much conversation upon the things of God, and I believe I may say that we both found we saw eye to eye, and, I trust, felt heart to heart in the precious truths of the everlasting gospel.He was a man of good, and I may say in some respects, deep experience of the life and power of God in the soul, knowing both law and gospel in their application and manifestation to the conscience beyond most men that we now meet with in the ministry or out of it. This made his conversation sweet, savoury, and profitable, and his ministry very searching and experimental; for indeed experimental ground was so completely his forte and drift, the feeling of his heart, and the words of his mouth, that off it he felt he could not stand, either as a man or a minister. He was also deeply afflicted, especially during the latter years of his life, with bodily suffering and internal disease, being scarcely ever free from pain, and sometimes very acute, for a single quarter of an hour a day.

In the autumn of 1862, he was visited with a most severe, long, and lingering illness, during which he approached so near to death as few have ever experienced who have again been raised up; and, indeed, nothing but the most careful and unwearied nursing, and most eminent medical skill could, humanly speaking, have brought him back. During that illness he was much blessed and favoured in his soul, and longed to depart, as desirous to be with Christ, which he felt was far better than living a life of pain to himself, though of profit to others.

But what particularly distinguished him, both as a Christian man and as a minister, was the uprightness, integrity, consistency, and godliness of his walk before the church and before the world. He was, I should say, naturally a man of somewhat stern disposition and unbending firmness of mind; though, to see him in his family, nothing could exceed his tenderness and affection, or as a tradesman, carrying on a large business that of watch- maker, silversmith, and jeweller, which brought him much into contact with the gentry and clergy of the town and neighbourhood, his obliging civility.

But with this sternness (the very stuff out of which martyrs are made) there was combined a remarkable, and, to my mind, sometimes almost painful degree of humility, so that I have said to him, “Most men are too proud, but you are too humble;” for his was not a mock humility, the worst cloak of pride, but a real sense of what he was or felt he was before God and man, which put him below his right place both as a Christian and as a minister. I have seen, therefore, a wisdom and a mercy in his being endued with that very sternness of mind and sometimes of manner, and with that firmness of which I have spoken, for it instrumentally preserved him from being trampled upon by those who would gladly have availed themselves of his very humility to exalt themselves by putting him lower than he put himself. A Christian man, and especially a Christian minister, should know his place and keep it too, and not allow the humility of mind which he feels before God to sink him below the real position which the Lord has given him in the church by his word, by his grace, and by the esteem and affection of his people. This was the reason why I used to tell him he was too humble; for both as a man well taught in his own soul, well instructed in the word, possessed of good natural abilities, and a very acceptable gift for the ministry, he would almost put himself below men who, with all their pretensions, had not half his grace, experience, knowledge, or gifts. He had, too, a good knowledge of the word, with a thoughtful and original insight into many deep and difficult passages, without any wild, novel, or visionary views, being of a singularly sober mind, sound in the faith, and well and experimentally led into those grand points of vital doctrine, such as the Trinity, the Sonship of Christ, the personality and work of the Holy Ghost, &c., which are so dear to those who believe and love the truth. And as he was vitally and spiritually acquainted with the truth, so was he most firm in preaching and maintaining it. His dying words to his dear wife, the true and affectionate partner of all his sorrows and joys in nature and grace, thoroughly express his character. “No compromise in the truth,” might be fitly written on his tombstone. He had bought it too dearly, and valued it too highly, to sell it at any price, or part with even the smallest portion of it, still less admit in its room any base substitute.

And as he did not compromise the truth in the pulpit by his lips, so he did not compromise it out of it by his feet. On this point he was exceedingly tender. I have heard him speak, with almost anguish of spirit, of his fears, lest he might be suffered to fall into any evil which might disgrace his profession, and open the mouths of the enemies of truth. But he was especially preserved not only from evil, but from the very appearance of it, maintaining both as a minister of the gospel a most unblemished character before the church and the world, and as a tradesman in a difficult business, and one in which there is so much room for imposition, the highest reputation for integrity, and thus gaining the greatest confidence of the very persons who despised and rejected his religion. He had seen and deeply felt the inconsistency of a professed religion, especially in his early days, when placed under circumstances of peculiar temptation, and, I believe I may add, surrounded by many professors, both whose doctrines and conduct were but little consistent with the spirit and precepts of the gospel. It is a point on which we have often conversed; but, as most of those have passed away by whose principles or example he might have been drawn aside, I shall not enter further into the subject. Suffice it to say that he was exceedingly opposed to anything like a light, inconsistent, unbecoming, antinomian spirit or conduct, and held firm and fast, both in preaching and practice, by the precepts of the gospel, which he considered had been much overlooked, and, if not altogether set aside, ignored and passed over almost as much as if they did not form an integral part of divine revelation. He felt, also, that he was placed in an important position in the town in which he lived; that many eyes were upon him, and some were watching for his halting. But he had the unspeakable satisfaction of a good conscience; for I have heard him say, not in a spirit of boasting, but humble thankfulness, that “there was not a single man,” and he added, with much emphasis, “not a single woman, since he had made a profession of religion, whom he could not look in the face without any cause of fear or shame.”

I was myself much attached to him, there being few men with whom I have felt more union of mind and spirit, or for whom I have had more real esteem and affection. I have generally, since 1860, spent a few days every year under his roof; and this, with the aid of correspondence by letter in which we fully and freely exchanged our thoughts, not only kept alive our union and friendship, but gave me the opportunity of knowing much of his mind and seeing much of the sterling weight of his religion and the intrinsic worth of his character in every relationship of life.

But he is gone. He died in the faith in which he lived, was favoured, on his dying bed, with the smiles of his God, and is entered into rest, where sin no more will grieve his soul, and pain no more afflict his body.

May we follow him as he followed Christ, and live and die as he lived and died, without a cloud upon our walk in life, and without a cloud upon our soul in death.

Joseph C. Philpot]

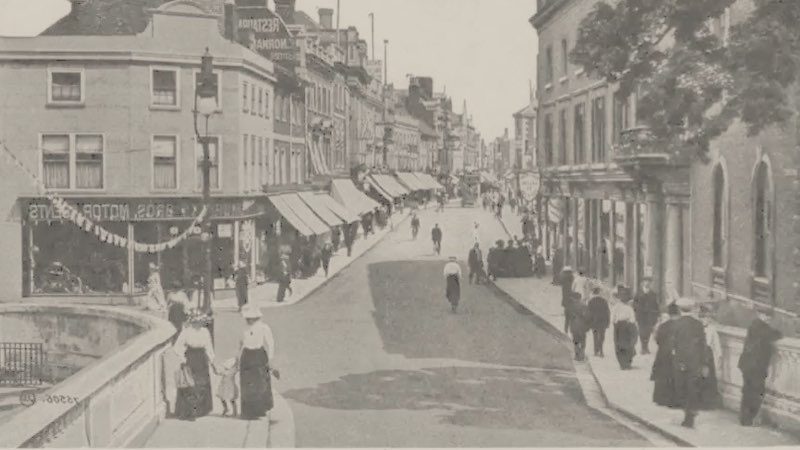

Joseph Tanner (1809-1867) was a Strict and Particular Baptist preacher. He served as pastor for the church meeting at Cirencester, Gloucestershire.