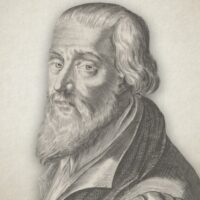

The Life And Martyrdom Of Nicholas Ridley

The Sower 1881:

This eminent divine, scholar, and martyr of the English Reformation was born in the county of Northumberland; and in the town of Newcastle he was taught the rudiments of education. From Newcastle he removed to Cambridge, where his learning and progress soon gained for him some of the highest honours that seat of learning had then to confer. He was made Doctor in Divinity, and he was also placed at the head of Pembroke Hall. At the conclusion of his university career, he made a tour on the Continent; and, when he returned to his country, emoluments were again offered him. He was appointed one of the chaplains to Henry VIII, and was afterwards elevated to the episcopal bench as Bishop of Rochester. Soon after the accession of Edward VI to the throne, Ridley was translated to the see of London.

We have commenced with this brief and rapid summary of Ridley’s early life, because it is not our intention to narrate every detail and circumstance of his career, as they have been handed down to us by credible historians. Not that we fear a close and thorough investigation of his life would tend to lower the worthy man in our estimation; for, on the other hand, we are fully satisfied that his character will bear examination and will stand the test of the strictest scrutiny. But, in dealing with a life like that of Nicholas Ridley, so replete with interesting incidents and noble actions, we are compelled to omit much that we should necessarily insert if we were writing a biography. We must therefore do our best to make such selections as will set forth his character, and thus endeavour to portray the man exactly as he was.

Ridley appears to have been a fine, handsome man, comely and well proportioned. Possessmg a very kind, cheerful, and forgiving disposition, he permitted no anger to lurk in his bosom, nor did he bear malice towards any person. His kindness to friends and foes was alike exemplary. To his relations he was most generous, but especially towards those who were of the “household of faith” would he extend the hand of pity and help. A striking instance of his benevolence is worthy of narration. When he was residing at Fulham, Mrs. Bonner, mother of the execrable Bonner, afterwards Bishop of London, and her daughter, both of whom lived in an adjacent house, were among his daily guests. Mrs. Bonner was always placed at the head of the dinner-table, and on no account would the good bishop have her removed from that position. On some occasions, distinguished visitors, such as bishops, members of the Privy Council, and others, would be present, when the place of honour was invariably occupied by this lady, whose Ridley would defend by saying, “By your lordships’ favour, this place of right and custom is for my mother Bonner.” Ridley could not have manifested more consideration and kindness to his own mother, and yet how, in after years, her son rewarded him! Bonner’s reward was a stake, and a glorious reward it was too, although this enemy of God’s truth did not intend it as such.

As a bishop, too, Ridley was a pattern. He was one of the “John Hooper” type—faithful, sincere, and zealous. Preaching the Word was his favourite, his chief occupation, and in that work he never wearied. It was his greatest delight to declare the truths of the Gospel, and no opportunity did he lose of speaking to his countrymen upon this all-important subject. Hundreds and thousands flocked to hear his sermons, so general and intense was the desire to hear the “glad tidings.” This was indeed a revival—a genuine revival of religion. Truth had been buried for ages; but, at the time of the Reformation, it arose from the grave to which ignorance and superstition had consigned it, to speak with a voice and act with a power that dashed monarchs from their honours and hurled nations from their pinnacles of greatness.

But we must not omit to speak of the scholarly abilities of Nicholas Ridley, for to these more than to anything else he owed his preferments at the university and his royal chaplaincy. We consider Ridley to have been the greatest scholar of the English Reformation. His varied and extensive reading, his earnest studiousness, and his retentive memory—such a rich cluster of qualities so essential to a man of learning—enabled Ridley to outstrip his rivals and become one of the luminaries of his day. But something higher and nobler than worldly learning has surrounded the name of Ridley with a halo of glory which time can never darken nor obliterate. However, we must not be understood to depreciate the value of a good education. There are men, and we have heard such, who denounce in a sort of wholesale style all human learning as productive of no good results. Such teachers make a great mistake. It is true that mere worldly learning has caused men to tread upon dangerous ground and propound dangerous doctrines. This, however, is the abuse, not the use of education. When a man whom God has been pleased to endow with brilliant abilities and moral qualities utilizes his learning, he is a useful member of society, and one certain to benefit the circle in which he moves. But when, as in the case of Ridley and Tyndale, human learning and natural talents are accompanied with the grace of God in the heart, then men are sure to become not only a moral, but a spiritual benefit to mankind. This good, be it remembered, they are enabled to effect by the divine favour of the Almighty.

But Ridley was not only a generous man—not only a brilliant scholar—he was also a Christian hero. It was the perusal of a little work on the Lord’s Supper, written by a monk named Bertram, that caused the existence of doubts in the mind of Ridley concerning the veracity of Rome’s teaching. This book was written in the ninth century, and was a clear and decisive protest against the dogma of transubstantiation. Step by step Ridley was led further from Rome and nearer to the Bible, until he finally renounced the faith of his fathers to ally himself with those whose highest ambition was to humbly serve Christ and His truth in their day and generation. In the days of King Edward he was one of the most active and indefatigable supporters of the Reformation; and during that short reign he worked with an untiring energy to establish the Gospel in the land. But his work was cut short by the death of the young monarch, and the elevation of Popery to power under a princess of the Romish faith.

Ridley was soon thrown into the Tower as one too busy and dangerous to be at liberty; and from thence he was transferred, in company with Latimer, to the Bocardo prison at Oxford; and here he continued until within eight months of his martyrdom, when he was confined in the private house of a man named Irish.

During their confinement in the Bocardo, Latimer and Ridley often spent sweet and pleasant hours together in prayer, meditation, and conversation. How gloomy indeed was their cell, but often how cheerful their hearts! The prison was at times a very Bethel to them, when they were visited by Him whom no iron bars nor massive doors can prevent from coming to the aid of those who truly need divine help and strength.

There were periods when they were not able to converse with each other, and then these two Christian heroes committed their thoughts to paper, thus encouraging and assisting one another as they journeyed onward through the wilderness. Thus Ridley desires his fellow-prisoner, because that he was “an old soldier and an expert warrior,” to help him “to buckle his harness;” and to this we find Latimer replying that Ridley had indeed “ministered armour unto him, whereas,” to use his own words, “I was unarmed before and unprovided, saving that I give myself to prayer for my refuge.”

These prison communications are intensely interesting, and they give a deep insight into the character of these two illustrious men. Honesty and sincerity shine in every line, and each sentence is an evidence of their genuine belief in the grand, experimental truths of the Gospel. Prison life was, after all, not such a dismal affair to them, for their souls were filled with peace and joy—such a peace and joy of which the world at large is ignorant.

During the long period of imprisonment which Ridley had to pass through, he wrote many beautiful letters to various parties, principally to those who, like himself, were suffering for the truth’s sake. One of these letters we will briefly notice. It is one that he addressed generally to all true lovers of and sufferers for the Gospel throughout the country. He commences by expressing his joy at the constancy and firmness of those who had been enabled to adhere to the cause of the Gospel, notwithstanding the crafty and potent efforts of their enemies to wean them from the same. He then, after referring to the various means used to carry out this object, breaks out in the following grateful language:—

“Yet blessed be the God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, which hath given unto you a manly courage, and hath so strengthened you in the inward man by the power of His Spirit that you can contemn so well all the allurements of the world, esteeming them as vanities, mere trifles, and things of nought; who hath also wrought, planted, and surely established in your hearts so steadfast a faith and love of the Lord Jesus Christ, joined with such constancy that, by no engines of Antichrist, be they ever so terrible or plausible, you will suffer any other Jesus, or any other Christ, to be forced upon you besides Him whom the prophets have spoken of before, the apostles have preached, the holy martyrs of God have confessed and testified with the effusion of their blood.”

“In this faith stand you fast,” continues the noble writer; “stand you fast, my brethren, and suffer not yourselves to be brought under the yoke of bondage and superstition any more; for you know, brethren, how our Saviour warned us beforehand that such should come as would point unto the world another Christ, and would set him out with so many false miracles and with such deceivable and subtle practices that even the very elect, if it were possible, should thereby be deceived. Such strong delusion to come did our Saviour give warning of before. But continue you faithful and constant, and be of good comfort, and remember that our great Captain hath overcome the world; for He that is in us is stronger than he that is in the world, and the Lord promiseth us that, for the elect’s sake, the days of wickedness shall be shortened. In the mean season abide you, and endure with patience as you have begun. ‘Endure,’ I say, and ‘reserve yourselves unto better times,’ as one of the heathen poets said. Cease not to show yourselves valiant soldiers of the Lord, and help to maintain the travailing faith of the Gospel.”

After telling them that they have need of patience to do the will of God, Ridley concludes this epistle with the following spirited sentences:—

“Let us be hearty and of good courage, therefore, and thoroughly comfort ourselves in the Lord. Be in no wise afraid of’ your adversaries, for that which is to them an occasion of perdition is to you a sure token of salvation, and that of God: ‘For unto you it is given, not only that you should believe on Him, but suffer for His sake;’ and, when you are railed upon for the name of Christ, remember that by the voice of Peter—yea, and of Christ our Saviour also—ye are counted with the prophets, with the apostles, with the holy martyrs of Christ, happy and blessed for ever, for the glory and Spirit of God resteth upon you. On their part our Saviour Christ is evil spoken of, but on your part He is glorified; for what can they else do unto you by persecuting you, and working all cruelty and villainy against you, but make your crowns more glorious—yea, beautify and multiply the same, and heap upon themselves the horrible plagues and heavy wrath of God? And, therefore, good brethren, though they rage ever so fiercely against us, yet let us not wish evil unto them again, knowing that while for Christ’s cause they vex and persecute us, they are like madmen, most outrageous and cruel against themselves, heaping hot burning coals upon their own heads; but rather wish well unto them, knowing that we are thereunto called in Christ Jesus, that we should be heirs of the blessing. Let us pray, therefore, unto God that He would drive out of their hearts this darkness of errors, and make the light of His truth to shine unto them, that they, acknowledging their blindness, may with all humble repentance be converted unto the Lord, and with us confess Him to be the only true God, which is the Father of light, and His only Son Jesus Christ, worshipping Him in spirit and truth. The Spirit of our Lord Jesus Christ comfort your hearts in the love of God and patience of Christ. Amen.

“Your brother in the Lord, whose name this bearer shall signify unto you, ready always by the grace of God to live and die with you.”

Before closing our sketch of this eminent servant of Christ, we will just briefly allude to his many examinations before the bishops. Ridley was too important a “heretic” to be dealt with too summarily, and therefore his episcopal judges manifested a semblance of leniency by giving him many opportunities of renouncing his principles and returning to the “Mother Church,” if he so felt inclined. But the longer they delayed the consummation of their cruel policy, the firmer did Ridley become in the truth of the Gospel. His answers to the interrogations of the bishops reveal Ridley to us as a two-fold character—as a man of learning and a man of truth. He was the possessor of natural talents and of spiritual grace. Any person who has been so industrious as to read and study attentively these examinations, has undoubtedly felt repaid for the trouble. The questions and harangues of the bishops, their enunciation and defence of Rome’s dogmas and practices, and their fine and plausible appeal to Ridley to abandon his principles and return to their creed, on the one side; and the heroic martyr’s clear and outspoken statements, the comparative ease with which he overthrows the pretensions of the Papacy by the Word of God, and his grand determination to go to the fire rather than betray his Master, on the other side—these are features that occupy an important place in the history of English martyrology.

On the first day of October, 1555, Ridley heard his sentence of condemnation read by the Bishop of Lincoln. After the reading of the document the noble man was handed over to the Mayor of Oxford, by name Mr. Irish, in whose house he had already been confined for several months. Exactly a fortnight elapsed before Ridley was visited by the Bishop of Gloucester, who offered him, on certain conditions, the Queen’s pardon. The nature of these conditions will be readily guessed, and we need hardly add that they were not accepted by the martyr. Ridley’s answer was characteristic of the man. “My lord,” replied the hero, “you know my mind fully herein; and, as for the doctrine which I have taught, my conscience assureth me that it was sound, and according to God’s Word (to His glory be it spoken); the which doctrine, the Lord God being my Helper, I will maintain as long as my tongue shall wag, and health is within my body, and, in confirmation thereof, seal the same with my blood.” The farce of degradation, as Ridley proved incorrigible, was then proceeded with, the good man protesting against the folly of the performance. When they had finished, he desired to reason with them, but they refused to listen to him. Ridley was then placed in the custody of the bailiffs, who were ordered to have their prisoner ready for the stake on the morrow at the appointed hour. Hearing the command, Ridley joyously exclaimed, “God, I thank Thee, and to Thy praise let it be spoken, there is none of you all [referring to his enemies] able to lay to my charge any open or notorious crime; for, if you could, it should surely be laid in my lap, I see very well.” The bishop told him he was a proud Pharisee. “No, no, no,” said Ridley; “as I have said before, to God’s glory be it spoken. I confess myself to be a miserable, wretched sinner, and have great need of God’s help and mercy, and do daily call and cry for the same; therefore, I pray you, have no such opinion of me.”

On the morrow he was to suffer, but the anticipation of the event only filled his soul with an unspeakable joy that astonished both his enemies and friends. At supper he was very cheerful, inviting his friends to his marriage, “for,” said he, “tomorrow I must be married.” He expressly desired his brother and sister to be present, and witness his last moments. Mrs. Irish, the mayor’s wife, was melted into tears at his calmness and cheerfulness. Ridley, trying to comfort her, said, “Oh, Mrs. Irish, you love me not, I see well enough; for in that weep, it doth appear you will not be at my marriage, neither are content therewith. Indeed, you are not so much my friend as I thought you had been. But quiet yourself; though my breakfast shall be somewhat sharp and painful, yet I am sure my supper will be more pleasant and sweet.” Animated with a joy and possessing a peace unknown to the world at large, Ridley could look death in the face, however cruel and tragic the form it might assume, knowing full well that it was but the door that admitted him into the realms of eternal bliss.

On the morrow, October 16th, 1555, two of England’s noblest sons, Nicholas Ridley and Hugh Latimer, were burnt at the stake for their love of Christ and adherence to His truth. It is not our intention to describe this grand scene in this place, as we have yet to trace the career of Latimer. Suffice it to say, then, that Ridley remained cheerful to the last, and flinched not from the fiery ordeal that his enemies prepared for him.

Nicholas Ridley (1500-155) was a Protestant Reformer and martyr. He was “Bishop of London and Westminster” (the only man to hold that title) and was one of the “Oxford Martyrs” burned at the stake under the reign of Bloody Mary.