The Life And Ministry Of William Perkins

Dictionary Of National Biography, Vol 45:

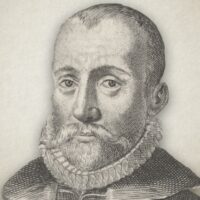

William Perkins (1558–1602), theological writer, son of Thomas Perkins and Hannah his wife, both of whom survived him, was born at Marston Jabbett in the parish of Bulkington in Warwickshire in 1558. In June 1577 he matriculated as a pensioner of Christ’s College, Cambridge, where he appears to have studied under Laurence Chaderton [q. v.], from whom he probably first received his puritan bias. His early career gave no promise of future eminence; he was noted for recklessness and profanity, and addicted to drunkenness. From these courses he was, however, suddenly converted by the trivial incident of overhearing a woman in the street allude to him as ‘drunken Perkins,’ holding him up as a terror to a fretful child.

In 1584 he commenced M.A., was elected a fellow of his college, and began to be widely known as a singularly earnest and effective preacher. He preached to the prisoners in the castle, and was appointed lecturer at Great St. Andrews, where both the members of the university and the townsmen flocked in great numbers to listen to him. According to Fuller (Holy State, ed. 1648, p. 81), ‘his sermons were not so plain but that the piously learned did admire them, nor so learned but that the plain did understand them;’ and he seems to have possessed the art of conducting his argument after the strictly logical method then in vogue, while preserving a simplicity of language which made him intelligible to all. His reputation as a theologian progressed scarcely less rapidly, and at a time when controversy between the anglican and puritan parties in the university was at its height, he became noted for his outspoken resistance to all that savoured of Roman usage in the matter of ritual. In a ‘commonplace’ delivered in the chapel of his college (13 Jan. 1586–7), he demurred to the practice of kneeling at the taking of the sacrament, and also to that of turning to the east. Being subsequently cited before the vice-chancellor and certain of the heads, he was ordered to read a paper in which he partly qualified and partly recalled what he was reported to have said. From this time he appears to have used more guarded language in his public discourses, but his sympathy with the puritan party continued undiminished, and, according to Bancroft (Daungerous Positions, ed. 1593, p. 92), he was one of the members of a ‘synod’ which in 1589 assembled at St. John’s College to revise the treatise ‘Of Discipline’ (afterwards ‘The Directory’), an embodiment of puritan doctrine which those present pledged themselves to support. In the same year he was one of the petitioners to the authorities of the university on behalf of Francis Johnson [q. v.], a fellow of Christ’s, who had been committed to prison on account of his advocacy of a presbyterian form of church government (Strype, Annals, iv. 134; Lansdowne MSS. lxi. 19–57). His sense of the severity with which his party was treated by Whitgift, both in the university and elsewhere, is probably indicated in the preface to his ‘Armilla Aurea’ (editions of 1590 and 1592), it being dated ‘in the year of the last sufferings of the Saints.’ In the same preface he refers to the attacks to which he was himself at that time exposed, but says that he holds it better to encounter calumny, however unscrupulous, than be silent when duty towards ‘Mater Academia’ calls for his testimony to the truth. He also took occasion to express in the warmest terms his gratitude for the benefits he had derived from his academic education. The ‘Armilla’ excited, however, vehement opposition owing to its unflinching Calvinism, and, according to Heylin (Aerius Redivivus, p. 341), was the occasion of William Barret’s violent attack on the calvinistic tenets from the pulpit of St. Mary’s [see Barret, William, fl. 1595]; but the work more especially singled out by the preacher for invective was Perkins’s ‘Exposition of the Apostles’ Creed,’ just issued (April 1595) from the university press, in which the writer ventured to impugn the doctrine of the descent into hell (Strype, Whitgift, ed. 1718, p. 439).

Against the distinctive tenets of the Roman church, Perkins bore uniformly emphatic testimony; and the publication of his ‘Reformed Catholike’ in 1597 was an important event in relation to the whole controversy. He here sought to draw the boundary-line indicating the essential points of difference between the protestant and the Roman belief, beyond which it appeared to him impossible for concession and conciliation on the part of the reformed churches to go. The ability and candid spirit of this treatise were recognised by the most competent judges of both parties, and William Bishop [q. v.], the catholic writer, although he assailed the book in his ‘Catholic Deformed,’ was fain to admit that he had ‘not seene any book of like quantity, published by a Protestant, to contain either more matter, or delivered in better method;’ while Robert Abbot [q. v.], afterwards bishop of Salisbury, in his reply to Bishop, praises Perkins’s ‘great trauell and paines for the furtherance of true religion and edifying of the Church.’

Perkins’s tenure of his fellowship at Christ’s continued until Michaelmas 1594, when it was probably vacated by his marriage. He died in 1602, having long been a martyr to the stone. He was interred in St. Andrew’s church at the expense of his college, which honoured his memory by a stately funeral. The sermon on the occasion was preached by James Montagu (1568?–1618) [q. v.], master of Sidney-Sussex College, who had been a fellow-commoner at Christ’s, and one of Perkins’s warmest defenders against the attack of Peter Baro [q. v.] His will was proved, 12 Jan. 1602–3, by his widow, whose name was Timothie, in the court of the vice-chancellor. To her he bequeathed his small estate in Cambridge, and appointed his former tutor, Laurence Chaderton, Edward Barwell, James Montagu, Richard Foxcroft, and Nathaniel Cradocke (his brother-in-law) his executors. To his father and mother, ‘brethren and sisters,’ he left a legacy of ten shillings each. Of his brother, Thomas Perkins of Marston, descendants in a direct line are still living.

Perkins’s reputation as a teacher during the closing years of his life was unrivalled in the university, and few students of theology quitted Cambridge without having sought to profit in some measure by his instruction; while as a writer he continued to be studied throughout the seventeenth century as an authority but little inferior to Hooker or Calvin. William Ames [q. v.] was perhaps his most eminent disciple; but John Robinson [q. v.], the founder of congregationalism at Leyden, who republished Perkins’s catechism in that city, diffused his influence probably over a wider area; while Phineas Fletcher [q. v.], who may have heard him lecture in the last year of his life, refers to him in his ‘Miscellanies’ thirty years later as ‘our wonder,’ ‘living, though long dead.’ Joseph Mead or Mede [q. v.], Bishop Richard Montagu [q. v.], Ussher, Bramhall (in his controversy with the bishop of Chalcedon, William Bishop), Herbert Thorndike, Benjamin Calamy, and not a few other distinguished ornaments of both parties in the church, all cite, with more or less frequency, his dicta as authoritative. By Arminius he was assailed in his ‘Examen’ (1612) with some acrimony; and Hobbes singled out his doctrine of predestination as virtual fatalism.

The observation of Fuller that it was he who ‘first humbled the towering speculations of philosophers into practice and morality’ indicates the real secret of Perkins’s remarkable influence. While he conciliated the scholarship of his university by his retention of the scholastic method in his treatment of questions of divinity, he abandoned the abstruse and unprofitable topics then usually selected for discussion in the schools, and by his solemn and impassioned discourse on the main doctrines of Christian theology—conceived, in his own phrase, as ‘the science of living blessedly for ever’ (Abridgement, p. 1)—he won the ear of a larger audience. Method and fervour presented themselves in his writings in rare combination; and Ames (Ad Lect. in the De Conscientia) expressly states that, in his wide experience of continental churches, he had frequently had occasion to deplore the want of a like systematic plan of instruction, and the evils consequent thereupon. Whether he actually disapproved of subscription is doubtful. According to Fuller, he generally evaded the question. He, however, distinctly gives it as his opinion that ‘those that make a separation from our Church because of corruptions in it are far from the spirit of Christ and his Apostles’ (Works, ed. 1616, iii. 389). His sound judgment is shown by the manner in which he kept clear of the all-absorbing millenarian controversy, and by his energetic repudiation of the prevalent belief in astrology. On the other hand, he considered that atheists deserved to be put to death (Cases of Conscience, ed. 1614, p. 118, ii. ii. 1).

The remarkable popularity of Perkins’s writings is attested by the number of languages into which many of them were translated. Those that appeared in English were almost immediately rendered into Latin, while several were reproduced in Dutch, Spanish, Welsh, and Irish, ‘a thing,’ observes John Legate [q. v.], the printer, in his preface to the edition of the ‘Collected Works’ of 1616–18, ‘not ordinarily observed in other writings of these our times.’ Of his ‘Armilla Aurea’ fifteen editions appeared in twenty years (Hickman, Hist. Quinq. p. 500).

William Perkins (1558-1602) was a sovereign grace preacher, theologian and writer. While serving as a cleric for the Church of England, he was sympathetic towards the non-conformists, becoming one of the leading voices for the Puritan movement during the Elizabethan era. He wrote more than forty books, among which is “A Golden Chain: Or, The Description Of Theology”. It explains the order of the causes of salvation and damnation, helpfully illustrated by a diagram which prefaces the work. He subscribed to a Supralapsarian view of God’s decree.