The Life And Ministry Of William Kiffin

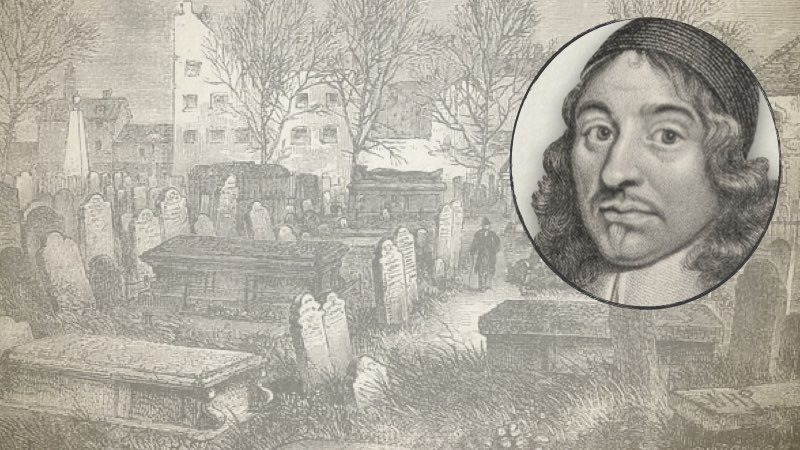

J. A. Jones, “Bunhill Memorials: Sacred Reminiscences Of Three Hundred Ministers And Other Persons Of Note, Who Are Buried In Bunhill Fields, Of Every Denomination” (1849):[1]

William Kiffin, Baptist. William Kiffin, the elder, of London, merchant, died December 29th, 1701, in the 86th year of his age.

The above was inscribed on his tombstone, as preserved by Mr. Strype, in Stowe’s Survey of London; but the intersection of his grave is not now known.

William Kiffin was so celebrated a person, and made such a distinguished figure in the seventeenth century, that the Editor has found it difficult to compress within the limits of this work, anything like a proper account of him. His long life comprehends a period commencing with the reign of James I., and ending fifteen years after the Glorious Revolution in 1688; consequently, embracing the events of the governments of Charles I., Oliver Cromwell, James II., and William III. His memoirs, chiefly written by himself, are a record of the wonderful providences of God, towards one of his humble, obedient, and most useful servants.

William Kiffin was born about the year 1616. He lost his parents at an early age; for it having pleased God to visit the metropolis with a dreadful plague, in 1625, they were both swept away by that dismal calamity, which proved nearly fatal to himself; for having six plague-boils upon his body, nothing but death was looked for; nevertheless, he wonderfully recovered. Being left an orphan at nine years of age, he was taken under the care of such of his friends as remained alive; but, they possessed themselves of the property left him by his parents. In 1629, he was put apprentice to John Lilburn, of celebrated memory, who was a brewer in London, but after the commencement of the civil war, obtained a colonel’s commission in the Parliament army. At this time young Kiffin had no sense of religion on his mind; but, growing melancholy on a’view of his outward condition, he left his master’s service early one morning. Wandering about the streets of London, he happened to pass by St. Antholin’s Church, and seeing some people go in, he followed them. The preacher, Mr. Foxley, was discoursing on the fifth commandment, and pointed out the duty of servants to their masters. He thought the preacher must have known him, and therefore addressed him personally. The effect was that he immediately returned back to his master, before his absence was discovered. More than that,—the impression made upon his mind by this discourse, caused him to resolve to attend the preaching of the Puritans.

Soon after, he went to hear Mr. Norton, who was the morning preacher at the same place. His text was Isaiah 57:18, “There is no peace saith my God to the wicked.” The minister took occasion to shew what true peace was; and that no man could obtain it without an interest in Jesus Christ. Which sermon (says Mr. Kiffin) took very great impression on my heart; being convinced I had not that peace, and, how to obtain an interest in Christ Jesus I knew not; which occasioned great perplexity in my soul. Pray, I could not; believe in Jesus Christ, I could not; and I thought myself shut up in unbelief. I desired to mourn over a sense of my sin, yet I saw that there was no proportion in my sorrow suitable to that evil nature which I found working strongly in my soul. I resolved to attend upon the most powerful preaching, by means of which I found some relief at times, drawn from a sense of a possibility, that, notwithstanding my sinful state, I might at last obtain mercy.”

After some time, hearing Mr. Davenport, in Coleman Street, preach from 1 John 1:7, “The blood of Jesus Christ cleanseth us from all sin” in which the preacher shewed the efficacy of Christ’s blood, both to pardon and cleanse; and answering some objections that the unbelieving heart of man would raise against that full satisfaction, which Jesus Christ has made for sinners; Kiffin says, “That sermon was of great satisfaction to my soul. I found my heart greatly to close with that rich, free grace, which God held forth to poor sinners, in Jesus Christ. I found my fears to vanish, and my heart became filled with love to Jesus Christ. I saw sin viler than ever; and my heart abhorred it more than ever. My faith became exceedingly strengthened in the fulness of that satisfaction which Jesus Christ had given for poor sinners, and I was enabled to believe my interest therein.”

The editor stays his pen. To follow Mr. Kiffin through all the variations of his experience (as narrated by himself) would be as the “balm of Gilead” to tried souls; but, the limits of this work will not permit a further detail. After some time, Mr. Kiffin joined himself to an ancient society of Independents. This church was the first Independent congregation which had been formed in England. It was collected in the year 1616, under the care of Mr. Henry Jacob. At the time Mr. Kiffin joined it (about 1634) the pastor was Mr. John Lathorp, who in the same year went to America, accompanied by about thirty of his congregation; Mr. Kiffin had resolved to go with him, but was prevented.

This being a time of great severity against the Nonconformists, the congregation was forced to meet very early in the morning, and continue together till late at night. He now began to exercise his abilities as a preacher. Being assembled one Lord’s day, at a house upon Tower Hill, as he was coming out, several rude persons who were about the door, assaulted him with stones, and one of them hit him on the eye. He writes,—“About a year afterwards (1635), I was sent for by a man, a poor smith, who lived in Nightingale Lane, and lay very sick. When I came to him he was so wasted, as to be reduced to almost skin and bone. He asked me, if I knew him! I said, I did not. He replied, that he knew me; for, said he, ‘1 am the man that disturbed your meeting at Tower Hill, and gathered the people together to stone you. At that time1was as strong as most men were, but, on my returning home from the place, I fell sick, and am wasted in my body to what you now see me.’ He intreated me, if I had any compassion for such a vile wretch as he was, that I would pray for him; which I accordingly did: but,—he died the same day.”

Mr. Kiffin having embraced the sentiments of the Baptists, he removed his communion from this church, and joined the Baptist Church, at Wapping, under the care of Mr. John Spilsbury. From this first Calvinistic-Baptist Church, the churches in Prescott Street, and Little Alie Street, have descended. About the year 1653, a controversy arising in the church, produced an amicable removal of several of the members who united with Mr. Kiffin; and to this separation the church in Devonshire Square owes its origin.

We must pass over some scores of interesting pages, narrating Mr. Kiffin’s eventful life in a way of Providence; and his many sore trials, persecutions, and imprisonments he underwent, as the result of the noble stand he constantly made for truth, and on behalf of religious liberty. In brief, he says,—“In the year 1643, I went over to Holland, with some small commodity [woollen cloth], from which I found good profit. At the end of the year 1645, seeing no way of subsistence, and that I was likely to be reduced to a very low condition in the world, observing that a young man, belonging to the congregation, walked very soberly, although be had but very little in the world, I discoursed with him about his going over to Holland, which I found him very willing to do, taking with him such commodity which I at first had found so profitable. And, although our stakes were very little, it pleased God so to bless our endeavours, as, from scores of pounds, to bring it to many hundreds and thousands of pounds: giving me more of this world than ever I could have thought to have enjoyed.” Mr. Kiffin then enters into a lengthened account of his obtaining from various sources, doubtless a very large fortune. The credit acquired by him as a man of business, procured him to be entrusted by the Parliament in 1647, as an assessor of the taxes to be raised for Middlesex; and his great affluence, united with the deserved esteem in which he was held, placed him amongst the foremost of his denomination in the city, and gave him great influence with the Dissenters in general.

But these were all temporal matters; proceed we now to glance (and merely glance) at some of the troubles he endured, and the sufferings he underwent for conscience-sake, and for his unflinching firmness in the cause of civil and religious liberty. Mr. Kiffin, in his political sentiments, was most strictly loyal; but, had he lived in our day, he would have been one of the first, in the Anti-State Church Association. O, I admire the noble note appended to the 48th article of the Baptist’s u Confession of Faith,” referred to on page 127, (Supposed to have been written by Kiffin.) I venture to transcribe a small part of it. “ The supreme magistracy of this kingdom we acknowledge to be king, and parliament, now established; and that we are to maintain and defend all civil laws, and civil officers made by them, which are for the good of the commonwealth. And we acknowledge, with thankfulness, that God hath made this present king and parliament Tumourable, in throwing down the Prelatical Hierarchy, because of their tyranny and oppression over us, under which the kingdom long groaned; for which we are ever engaged to bless God, and honour them, for the same.” “Concerning the worship of God, there is but one Lawgiver which is Jesus Christ: and, surely, it is our wisdom, duty and privilege, to observe Christ’s laws only; and thrice happy shall he be, that shall lose his life for witnessing (though but for the least tittle) of the truth of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

Kiffin had to wade through seas of trouble; for his lot was cast to live in u troublous times but he “chose to suffer affliction with the people of God.” The spirit of the times did not suffer him to be long at rest. Very serious attacks were constantly making both upon the civil and religious liberties of the people. The High Commission Court, under the direction of Laud and the Prelates, was guilty of the most horrid barbarities; so that the people groaned for emancipation from the yoke of their worse than Egyptian task masters. The demon of persecution was let loose; and the unprotected Dissenters were hunted as a partridge upon the mountains; many of them were compelled to sacrifice their liberties, their property, and in some cases their lives, to gratify (alas! not to satisfy) the implacable malice of those who were saying of their principles, as the enemies of old did of Zion, “Raze it, raze it, to the very foundation.”

A little before the restoration of Charles II., Mr. Kiffin, with several others, were seized at midnight by soldiers, and

carried to the guard-house at St. Paul’s; from whence they were liberated by the Lord Mayor, Sir Thomas Almin, who was satisfied of their innocence of what was alleged against them. After a time a plot was laid against him by means of a forged letter, purporting to have been sent him from Taunton; which, said he, “had it taken effect would have cost me the loss of life and estate.” Out of this snare the Lord delivered him. Then again, being at a meeting in Shoreditch on a Lord’s day, he was apprehended and carried before Sir Thomas Bide, who committed him and some others, to the new prison. At another time, he says, “I was seized by one of the messengers of the Privy Council, by order of the Duke of Buckingham. I was taken to York House, and continued there till the next night, under the care of soldiers. In the evening the duke came to me, and told me that, I would have hired two mm to kill the king! but adding, ‘if I would confess the truth, care should be taken that I should not suffer.’ A long account is given of this matter; suffice it to say that, out of this snare the Lord also delivered him.

In the year 1679, the spirit of persecution against Dissenters revived, and Borne new clauses were also added to the u Conventicle Act,” which were enforced with greater severity than ever, by bigoted prelates, and oppressive magistrates. Mr. Kiffin was considered fair game for the informers. He says, “I was taken at a meeting, and prosecuted for the purpose of recovering from me forty pounds. This sum I deposited in the hands of the officer; but, owing to some error in the proceedings, I overthrew the informers; though the trial coat me thirty pounds.” He further says, “I was again prosecuted by the informers for three hundred pounds, the penalties of fifteen meetings. They had managed this matter so secretly, as to get the record in court for the money.” It seems they were again foiled; and the informers were obliged to let the suit fall. This conduct of Mr. Kiffin displays great intrepidity, in defence of the rights of English men; and his success, in defending himself against the harpies of the State, must have greatly availed to promote the liberty of the subject. His domestic afflictions were very severe. He says, “It pleased God to take out of the world to himself, my eldest son, which was no small affliction to me and my dear wife. The grief I felt for his loss did greatly press me down with more than ordinary sorrow; but it pleased the Lord to support me by that blessed word being brought powerfully to my mind, “Is it not lawful for me to do what I will with mine own?” These words did quiet my heart, so that I felt a perfect submission to his sovereign will; and it became a voice to me, to be more humble and watchful over my own ways.”

This son, named also William, lies buried in the same grave with his father, in Bunhill. His next son, being of a weak constitution, was sent abroad for his health. On his returning home, when at Venice, he met with a Popish priest, and being forward to discourse with him about religion; the priest, to show his revenge, destroyed him by poison.

But, the sorest trial this holy man of God experienced, was in the loss of his two grandsons, Benjamin and William Hewling, who were executed for the part they took in the affair of Monmouth’s rebellion.” Those dear youths, the elder was only 22 years of age, the younger had not reached his 20th year! Of all the unhappy victims that were sacrificed upon this occasion, none were more pitied than these two brothers; and the flintiness of the king’s heart cannot be more strikingly illustrated than in their fate. “Madam (said Lord Churchill, to Hannah Hewling, their sister, who came to present a petition to his majesty on their behalf) I dare not flatter you with any hopes, for that marble is as capable of feeling compassion as the king’s heart.” Such is Popish tenderness. Kiffin says, “At the trial of William Hewling, the Judge Jefferies told him, in public court, that ‘his grandfather did as well deserve the death which he was likely to suffer, as himself.’ I mention this, said Kiffin, that it might be seen what an eye they had upon me for my ruin, if the Lord, who watched over me for good, had not prevented.” But this subject is too painful to pursue. By and by, even James’ day of retribution arrived. On one occasion, Kiffin being ordered to attend at Court, the king immediately came up to him, and addressed him with all the little grace he was master of. He talked of his favour to the Dissenters! in the Court style of this season. “Sire,” replied Kiffin, “I am a very old man, and have withdrawn myself from all kinds of business for some years past, and am incapable of doing you any service. Besides, Sire”—the old man went on, fixing his eyes stedfastly on the king, while the tears ran down his cheeks—“the death of my grandsons gave a wound to my heart, which is still bleeding, and never will close but in the grave.”—The King was deeply struck by the manner, the freedom, and the spirit of this unexpected rebuke. A total silence ensued, while the galled countenance of James seemed to shrink from the horrid remembrance. In a minute or two, however, he recovered himself enough to say, “Mr. Kiffin, I shall find a balsam for that sore:” and he immediately turned about to a lord in waiting.—A similar reproof, equally unexpected, and as equally deserved, this unfeeling monarch received, at an extraordinary Council, which he called soon after the landing of the Nation’s deliverer the Prince of Orange. Here, amidst the silent company, he applied himself to the Earl of Bedford, father to the beheaded Lord William Russell, saying, “My Lord, you are a good man, and have got great influence; you can do much for me at this time.” To this the Earl replied, “I am an old man, and can do but little,” he then added, with a sigh, “I had once a son, who could now have been very serviceable to your majesty!” which words struck the king half dead, and he turned away in silence and confusion.

Seldom do we read such a deep tragedy in real life, as that in the family of this good man, at a time when popish principles prevailed in the government; and seldom, or never, have we read of such firm and intrepid conduct in a man, whom no dangers could terrify, no honours allure; nor could bribes blind his eyes or corrupt his hands. A writing, published by the Baptists, in London, in 1688, to which his hand is first signed, contained the grand sentiment, that governed his conduct in all religious, and in all political matters.—“It being our professed judgment, and we, on all occasions, shall manifest the same, to venture our all for the Protestant religion, and the liberties of our native country. And we do, with great thankfulness to God, acknowledge his special goodness to these nations, in raising up our present King William, to be a blessed instrument, in his hand, to deliver us from popery and arbitrary power, &c.” This noble declaration may be found at large in “Ivimey’s history of the Baptists,” vol. iii. page 335.” It is signed by William Kiffin, Hanserd Knollys, Andrew Gifford, Benjamin Keach, and twenty other ministers’ names.

The liberty which Mr. Kiffin and his brethren enjoyed after the Revolution, was improved for the purposes of settling the churches, &c. His congregation now assembled in their meeting house, in Devonshire Square, which place had been built by them, and was opened for public worship, on Match 1st, 1686-7. The concluding part of Mr. Kiffin’s manuscript was written by him, in 1693. He says therein, “Having tasted the goodness of God, and his favour towards me from my youth; it being now sixty years since it pleased the Lord to give me a taste of his rich grace and mercy of Jesus Christ to my soul; although my unprofitableness under these mercies hath been very great. The providences that

have attended me are not to be looked upon as products of chance, but as fruits of the care and goodness which God is pleased to show to his poor people while they are in the world; as there is no design hatched against them for their ruin, but they are rescued from them by the special care and providence of God. And truly I may say, by experience, “If the Lord had not been my help, they would many a time have swallowed me up quick!”

“I leave these few instances of the Divine care, to you my children, and grandchildren, and great grandchildren; that you may remember them with thankful hearts, as they must prove to the praise of God, on my account. I leave them also, desiring the Lord to bless them to you: above all, praying for you, that you may, in an especial manner, look after the great concerns of your souls; that you may know God, and Jesus Christ, whom to know is eternal life. I must every day expect to leave the world, having lived in it much longer than I expected; being now in the seventy-seventh year of my age, and yet know not what my eyes may see before my change. The world is full of confusions; the signs of the times are very visible; iniquity abounds; and the love of many, in religion, waxes cold. God is, by his providence, shaking the earth under our feet; there is no sure foundation of rest and peace, but only in Jesus Christ: to whose grace I commend you.”

Mr. Kiffin lived about eight years after the period to which he brought down his manuscript. In the interim, more afflictions befell him. In the year 1698, his son, Harry Kiffin, was removed by death, aged 44. Also, his grandaughter, Henrietta, the wife of Mr. John Catcher, died in the same year, aged 22. At length he himself also entered the harbour of peace and eternal rest, by falling asleep in Jesus.

This worthy man died, December 29th, 1701, in the 86th year of his age; having been pastor of the Baptist church, in Devonshire Square, upwards of 60 years. On his tombstone, in Bunhill Fields, were inscriptions concerning his son William, died in 1669; his daughter Priscilla, died 1679; his own beloved wife, Hannah, with whom he had lived 44 years, who died, Oct. 6th, 1682, aged 67. His son, Harry, who died in 1698; his grandaughter, Henrietta, in 1698; then follows, last of all, himself; all resting in one grave. “The memory of the just is blessed.”—W. and I. The tombstone is gone; and the precise spot of interment unknown.

——————————-

[1] The reader is encouraged to visit Bunhill Fields, a nonconformist cemetery located at 38 City Road, London, England.

William Kiffin (1616-1701) was a Strict and Particular Baptist preacher. In disagreement with the church at Wapping (under the pastoral care of John Spilsbury) for admitting to the pulpit unbaptized preachers, he organized in 1638 a new church meeting at Devonshire Square, which became the first Strict and Particular Baptist congregation in London on record. He is therefore sometimes called “the Father of the Strict and Particular Baptists”.