Notes On “Fullerism”

A main error of Mr. Fuller—and perhaps it was that in which his system, and the arguments by which he defended it, originated—consisted in the excessive and anti-scriptural ideas he formed of the accountableness of man. He attached obligations to him as a free agent, which, in fact, never devolved upon him by any law of his Creator, and invested him with a responsibility for talents which he never possessed. Because man is naturally obliged as a creature to love and obey God, according to the extensive purity and requirements of the Divine law, be maintained that the same reason in which his natural obligation as a creature was founded obliged him also, as a sinner, to believe in the Lord Jesus Christ for salvation upon his having the Gospel revelation. Independent of the absurdity of representing faith in Jesus, in a light which classes it with the works of the law, I call this an excessive and extravagant idea of human responsibility. Accountability, if it relates to anything, must relate to some service to be performed according to the measure of ability with which the Creator originally endows us, or to some trust with which He has charged us, that we may employ it for all purposes of His righteous will—or to some talents which He has given, that we may improve them, and return to Him that revenue of praise to which He is entitled—but accountability can have no place in the reception of gifts and benefits, which He communicates, with an absolute sovereignty of will, to whom He pleases. How can anyone be responsible for the gifts of a benefactor which he never received, or account for property with which he was never entrusted? A peasant is bound to observe allegiance to the sovereign and the government under which he lives, and to behave himself peaceably and justly towards every member of the community; if he violates the law, he is answerable for the offense at the bar of his country, and will be punished according to the nature of his crime. But who ever imagined that a peasant is culpable and entitled to punishment for a capital crime because he has not advanced himself to the rank of a peer in the realm, and secured himself a pension for life from the king’s treasure? If a proceeding of such a kind is absurd in supposition, because at variance with all the known principles and rules of equity and justice, yet such a proceeding actually takes place under the Divine Government, according to Mr. Fuller’s notion of accountability, which obliges a service under the Gospel to receive salvation by faith, under pain of death, because he is obliged by the law to obey the Divine will.

Of all the benefits and blessings of grace, which is it that the possession or enjoyment thereof hinges upon the accountability of man, or, rather the responsibility of a dead sinner? Is it Election? (Rom. 8:29, 30, 9, 11:5, 6; Eph. 1:3, 4). Redemption? (Rom. 5:7, 8). Reconciliation? (Rom. 5:10). Justification? (Rom. 3:21-28, 8:3, 4, 10:4). Faith? (Eph. 1:19, 2:8 ; Phil. 1:29; Col. 2:12; .John 6:21; Acts 13:48, 14:27). Or even personal and practical holiness and obedience? (Ezek. 16:60, 63, 36:25-27; Jer. 32:38-40). Search these and other scriptures of a similar import, and compare them with the work of God in your personal experience, and you will see indeed that you must put the crown of salvation where you delight to see it on the head, not of human accountableness, but the sovereignty of Jehovah’s grace. Under this view I am sure you will join with me in the most unfeigned abhorrence of a system that robs Him of His glory, and enhance the condemnation of the guilty to an immeasurable degree by increasing their responsibility.

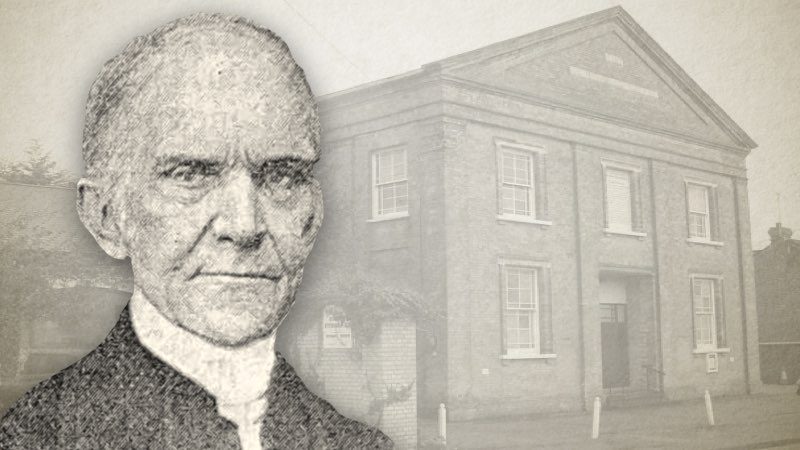

“Memorials of George Wright”, by S. K. Bland.

George Wright (1789-1873) was a Strict and Particular Baptist preacher. In 1823, he was appointed pastor of the church meeting in Beccles, Suffolk. The chapel in which they eventually met was called The Martyrs’ Memorial on account of its locality to the site where three men were executed for their faith under the reign of Queen Mary.