Come, Thou Almighty King

Psalm 113:1-9: “Praise ye the LORD. Praise, O ye servants of the LORD, praise the name of the LORD. Blessed be the name of the LORD from this time forth and for evermore. From the rising of the sun unto the going down of the same the LORD’s name is to be praised. The LORD is high above all nations, and his glory above the heavens. Who is like unto the LORD our God, who dwelleth on high, who humbleth himself to behold the things that are in heaven, and in the earth! He raiseth up the poor out of the dust, and lifteth the needy out of the dunghill; that he may set him with princes, even with the princes of his people. He maketh the barren woman to keep house, and to be a joyful mother of children. Praise ye the LORD.”

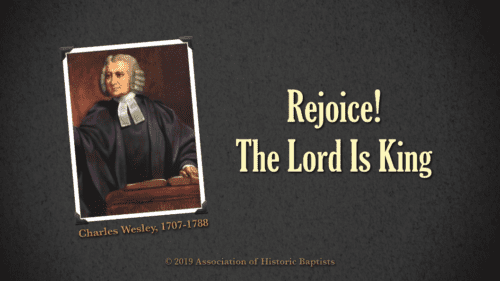

Charles Wesley (1707-1788) was one of the early pioneers of the Methodist movement, a preacher of the gospel and a hymn writer. As his views of the gospel matured, so did his convictions in sovereign grace. According to John Gadsby,

“Charles Wesley, and also his brother John, were born at Epworth, in Lincolnshire, of which parish their father, Samuel Wesley, was rector. Charles was born Dec. 18th, 1708, old style, that is, Dec. 29th. When about eight years of age, he was sent to the Westminster School, and in 1726 was elected a student of Christ Church, Oxford. Charles admits that he spent the first two years at Oxford negligent of religion; and when his brother John had spoken to him to be more serious, he would reply, "What! would you have me to be a saint all at dnce?" About 1731, Charles went with his brother and Mr. Ingham to Georgia, but, after laboring there about a year, suffering much from dysentery, he was obliged to return. He was not, as yet, acquainted with the power of religion, having been satisfied with using forms of prayer, &c. By reading the Life of Halliburton, "Charles was greatly stirred up to pray for the great blessing, and obtained salvation of the Lord;" whereupon he composed the hymn, "for a thousand tongues to sing."

When leaving America the second time, in 1736, the ship was not sea-worthy, and they had to put into Boston for repairs. He was there delayed a month, and then put out again; but again the ship was found unsafe. A storm arose, and Charles was, as he says, very uncomfortable. "I strove vehemently to pray," says he, "but in vain. I persisted in striving, yet still without effect. I prayed for power to pray, continually repeating the name of Jesus, till I felt the virtue of it at last. I felt the comfort of hope, and such joy in finding that I could hope, as the world can neither give nor take away. I had that conviction of the power of God present with me, over-ruling my fear and raising me above what I am by nature, as surpassed all rational evidence, and gave me a taste of the divine goodness." The captain was scarcely ever sober, and left the ship to the mate. They arrived safely at Deal, however, on Dec. 3rd. In 1739 Charles commenced his itinerant labors, and, "for the space of 10 years," says a Wesleyan biographer, "we must admit that his ministry was like a flame of fire." He laid his skeletons of sermons aside, and endeavored to preach with the unction and power of the Holy Ghost. Hundreds of sinners were converted to God; and some, who afterwards became ministers, including Thomas Maxfield, were called under his sermons in the open air. He often warned the people not to think they had new heart; merely because they had felt the deceitfulness of the old, nor to think they would ever be above the necessity of praying. A stroller once told him he would, for five shillings, show him how to make money. Charles said he had no need of money; but, giving the man sixpence, said, "as you possess the art of transmutation, you can, of course, easily make it into half a guinea." In common with the other Methodists, Charles was in perils oft. At Sheffield the mob completely pulled down the Society House in which he intended preaching, and an officer seized him, and pointed his sword to his breast; but, as Charles was undismayed, the officer somewhat lowered his tone. He was, however, hit with several stones thrown at him by the mob. One man once went up to him with a French sickle, to cut him down, but could not raise his arm. Charles saw him making great effort to do so, and exclaimed with a strong voice, “In the name of the Lord Jesus, keep back!” The man was struck with awe, and retired. At a place near Leeds, the mob once broke all the doors and windows of the house in which Charles was. They were indicted for a riot; but the leaders of the mob got up a cross suit, declaring that the Methodists had commenced the riot. It will show the spirit of the age, and give some idea of what the Methodists had to endure, when I mention the fact that the grand jury threw out their bill, and found a "true bill" against them. They were, however, acquitted on the trial. Charles was once preaching in the woods in America when he suddenly changed his position, and a shot at the same instant whizzed past him, and struck the tree he had just left. He at that time lived in a miserable hut, and had barely the necessaries, certainly not the comforts, of life, often sleeping on the floor, and valuing boards, when he could get them, as a luxury. I have already said so much about Charles Wesley, in conjunction with the other Methodists, that I must not enlarge here. In many of the acts of his brother John, Charles could not concur and when John used Whitefield in the way that he did, depriving him even of his own place of worship at Bristol, Charles clave to Whitefield, like Jonathan to David. Indeed, Philip, in his "Life and Times of Whitefield," says, "Charles, in 1752, consulted Whitefield on a delicate subject—separation from John. It embarrassed Whitefield. He knew not what to say. Something, however, rendered it necessary for him to say that he thought John still jealous of him and his proceedings. But, lest this should injure John with Charles, he said also, ‘The connection between you and your brother has been so close, and your attachment to him so necessary to keep up his interest, that I would not willingly, for the world, do or say anything that might separate such friends.' Wesley was somewhat jealous of Whitefield at this time. A new tabernacle was spoken of, and for a long time the nobility had smiled on Whitefield. Wesley felt this. He could have taken their smiles more coolly than Whitefield, but he could not sustain their neglect philosophically. It was, however, the contrast, not the loss that mortified him." So much for Philip. At the time of the eruption between John Wesley and Lady Huntingdon, Charles expressed himself very much grieved, and said that he should not fail to "speak to his brother roundly upon the subject." Somewhere about the year 1760, Charles gave up itinerating with his brother. Whenever Lady Huntingdon went to Clifton or Bath, Charles usually accompanied her. It is remarkable that the last 30 years of Charles's life have been inserted in about half a dozen pages by most of the Wesley biographers. All these things go to prove that Charles was hardly considered one of them. Up to 1749, all the hymns published by the Wesley's were published in their joint names, John and Charles; but at the end of that year, being about the time that Charles began to have a little insight into his brother's plans, Charles published in his own name only. Indeed, it is clear that he could not submit to his brother's mutilations, for nearly all the hymns were composed by Charles. Mr. Creamer, whom I have referred to in my memoir of Toplady, says, "Nearly every one of Watts's Hymns in the Wresleyan Hymn Book has been subject to just such a correction and revision as Mr. Milner" (who had called them hyper-Calvinistic) “had sagacity enough to see they required; and that, too, by no less a personage than the same who revised, and expurgated and re-revised the productions of Charles Wesley;" that is, by John Wesley. Is not this saying that Charles's, like Watts's, were too Calvinistic for John? The first hymn book which the Wesleys published was issued in 1738, entitled, "Psalms and Hymns." It was a small book; but in 1739, one of 2 vols, was published, "Hymns and Sacred Poems, by Messrs. John and Charles Wesley." The hymns were, however, as I have just said, nearly all by Charles. John was merely the amputator, or mutilator, or, as Mr. Creamer would say, the "reviser." In this, and other of the earlier productions of Charles Wesley, many hymns appear which have been ascribed to various persons; and I confess I was both surprised and delighted when, in these old books, I first caught sight of the originals. For some of these, I refer my readers to page 126, and now merely add the following: "Hark! the herald angels sing;" “Head of the church triumphant;" "Christ the Lord is risen to-day;" “Let earth and heaven combine;" "Blow ye the trumpet, blow;" and also hymns 127, 161, 229, 243, 249, 303, 390, 391, 408, Gadsby's Selection. In 1779, John published the first edition of the Wesleyan Selection. It contained 560 hymns. The Conference added a Supplement some years ago; so that the book now contains 769 hymns, 625 of which were composed by Charles, and only five by John; 24 are translations from the German (principally Moravian); one from the Spanish; and one from the French. That Charles was a good and gracious man, no one who has ever felt his own sinfulness and helplessness and the overwhelming power of redeeming love, and who reads Charles's hymns, can well doubt, unless he be prepared at the same time to say that he was one of the greatest hypocrites that ever lived; with which assertion I cannot for one moment sympathise. In my opinion, he was one of the sweetest hymn writers that ever existed. There may not be in his hymns that height of doctrine which is portrayed by Kent, Watts, &c, nor that depth of experience which shines so transcendently in Hart; but there is a life, and a breathing out of that life, in most of them which is not by any means approached by Watts, and which is certainly not surpassed by even Hart. A short time before he died, he called his wife to him, and requested her to write the following lines as he dictated them:

"In age and feebleness extreme,

Who shall a sinful worm redeem?

Jesus! my only hope thou art,

Strength of my failing flesh and heart.

Oh! could I catch a smile from thee,

And drop into eternity."

He said no fiend was permitted to approach him, and added, "I have a good hope." On being asked if he wanted anything, he replied, "Nothing but Christ." Some one said to him, "The valley is a hard one to pass;" to which he replied, “Not with Christ." Referring to a person who had been a bitter enemy, he prayed for her: “I beseech thee, by thy dying and bloody sweat, that she may never feel the pangs of eternal death!" His last words were, "Lord—my heart—my God!" He drew his breath gently, and his spirit departed, March 29th, 1788. He was interred in the church yard of St. Marylebone, London, near his own residence in Chesterfield Street. His brother John had much wished that he should be interred in his chapel yard, where he himself hoped to be laid; but Charles would never consent.”