The Cause Of True Religion

March 30, 1835.

My dear sister Fanny,—The tidings I am about to communicate may concern you more than surprise you. After many trials of mind about it, I have come to the resolution of seceding from the Church of England. In fact I have already resigned my curacy, and shall, in a day or two, give up my Fellowship. I could have wished to have retained my income and independence, but, as I could not do so with a good conscience, I was compelled to give it up. The errors and corruptions of the Church of England are so great and numerous that a man, with a conscience made tender by the blessed Spirit, cannot, after a certain time, remain within her pale. And though I have thus resigned my ease and income, I feel my mind more easy and at liberty, and trust I shall never come to poverty. My needs are now much less than they used to be, and I trust I shall be content with such slender fare as I may have to expect. Life is short, vain, and transitory; and if I live in comfort and ease, or in comparative poverty, it will matter little when I lie in my coffin! I trust, if I have health and strength given me, I shall not be a burden to my dear mother.

The cause of true Religion has, indeed, spoiled all my temporal prospects, and, doubtless, made the worldly and carnal think me a fool or mad. But, after all, the approbation of God and the testimony of an honest conscience are better than thousands of gold and silver. My resolution was rather suddenly executed. I had thought of giving my incumbent notice that I should resign the curacy at Midsummer. But it seemed to me inconsistent to tell my incumbent that I could not continue in the curacy but a certain time because I was doing evil. It was as though I had said to him, “Will you allow me to do evil for three months to come?” So I resolved to resign it at once, especially as my assistant promised to undertake it, if required, for the ensuing quarter. I told only two people of my intention, and having, on Sunday the 22nd, preached in my usual way, I added at the end—”You have heard my voice within these walls for the last time. I intend to resign the curacy and withdraw from the ministry of the Church of England.” It was as if a thunderbolt had dropped in the congregation. I did not wish any excitement or manifestation of feeling, and therefore shut it up as quickly as possible. The people were much moved. And the next day some met, and said they could build me a chapel if I would consent to stay. To this, however, I do not feel inclined, though the people wish it much, and say it should not cost me a farthing.

I think, God willing, at present, of staying at Stadham until some time in June, and then I shall probably go to a place called Allington, near Devises, Wilts, where there is a chapel in which I shall preach. The deacon heard me preach about one year and a half ago, and as soon as he heard I had left the Church of England, he had his horse saddled and rode to Stadham to see me. I happened to be here where he came. So I have consented to go to Allington for a few weeks.

I am now writing a letter, which I mean to publish, to the provost of Worcester College to resign my Fellowship, containing my reasons for seceding from the Established Church. It will be not more than twopence or threepence. If you would like to have some copies, I will ask the London bookseller to send you a hundred or so. It will be rather strong against the University and the Church of England system.

I trust that my dear mother will not be much hurt at this step I have taken, and I sincerely trust I shall prove no burden to her. The disgrace and the financial hardships, I do not think she will mind. The reproach of Christ is greater riches than the treasures of Egypt. At present I can speak nothing as to my future plans. I may spend some little time with you in Devon, and obtain that rest which I find necessary after preaching, and I trust the good Lord will never leave nor forsake me. He has many ways to provide for His servants, and can make the ravens feed them as Elijah of old. If I had health and strength, I might be able to make a living from preaching, or might keep a school. But at present I can say nothing, as I do not see my way clear, as to anything. Sufficient for the day is the evil thereof.

I have been staying here, at my friend Tiptaft’s, since Saturday, and I shall stay a day or two longer. So that I do not know whether you may not have already written to me. Direct your letter Stadhampton as usual, and tell me what you have settled about going into Devon.

This life is soon passing away, and an eternal state fast coming on. The grand question is, What do we know of Christ by the inward teachings of the Spirit? What true faith have we in a Savior’s blood and righteousness? What do we know of His having died for us?

The time of the post going presses so that I will add no more than that I am, with love to my dear mother and all your circle,

Your affectionate Brother,

J. C. P.

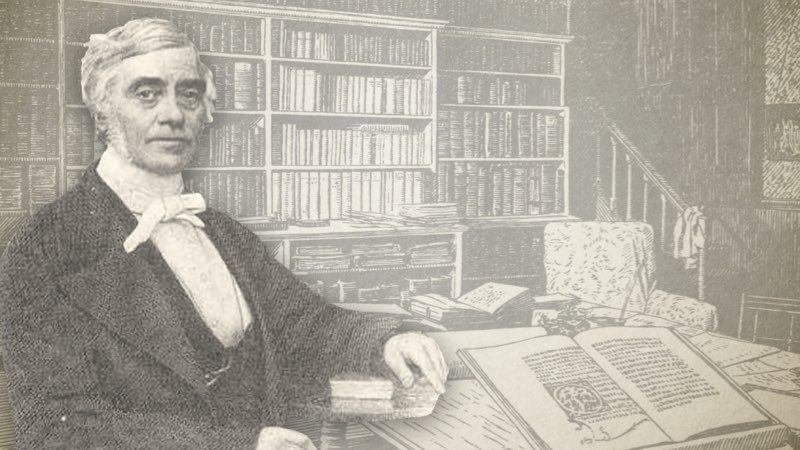

Joseph Philpot (1802-1869) was a Strict and Particular Baptist preacher. In 1838 he was appointed the Pastor of the Churches at Oakham and Stamford, during which time he became acquainted with the Gospel Standard. In 1849, he was appointed the Editor for the Gospel Standard Magazine, a position he held for twenty-nine years (nine years as joint Editor and twenty years as sole Editor). John Hazelton wrote of him—

“A man of great grace, profound learning, and with a literary style equal to any of his contemporaries. For twenty years he was editor of the "Gospel Standard," in which his New Year's Addresses, Meditations, Reviews, and Answers to Correspondents were outstanding features. His ten volumes of sermons, entitled "The Gospel Pulpit," and his four volumes of "Early Sermons," testify to his powers as an expositor of the Word, to the beauty of his illustrations, and the heart-searching character of his ministry. He was born at Ripple, Kent, where his father was rector, and educated at Merchant Taylor's and St. Paul's schools, entering at Oxford University in 1821, taking a first-class, and ultimately becoming Fellow of his College. He accepted an engagement in Ireland as a private tutor, but prior to his departure he was unexpectedly detained at Oakham. There he bought a book, "Hart's Hymns," and was much struck by the beauty of many of them. In 1827, in Ireland, eternal things were first laid upon his mind, and "I was made to know myself as a poor lost sinner, and a spirit of grace and supplication poured out upon my soul." He returned to Oxford in the autumn, and "the change in my character, life, and conduct was so marked that everyone took notice of it." Early in 1828 he was appointed to the perpetual curacy of Chislehampton, with Stadhampton—or Stadham—not far from Oxford. He soon gained the love and esteem of his parishioners. His Church was thronged, and his labours were unceasing amongst young and old. In 1829 he became acquainted with William Tiptaft (1803-1864), vicar of Sutton Courtney, and a friendship commenced which death alone severed. Both ministers had been led to know the truths of predestination and election and the final perseverance of the saints, and preached them with unflinching boldness. Persecution soon arose; it always does in some quarter when there is a faithful ministry. In 1831 Tiptaft built a chapel at Abingdon, where he remained as a Baptist pastor until his death. In 1835 Mr. Philpot resigned his living and his fellowship; the temporal sacrifice entailed was such that he had to sell almost all his books. Soon after this momentous step had been taken he preached in a chapel at Newbury, which some of his friends had procured for the purpose. He writes: "When I therefore began to open up that God had a chosen and peculiar people the whole place seemed in commotion. One man called aloud, 'This doctrine won't do for me!' and started out, and was instantly followed by five or six others. I was not, however, daunted by this, but went on to state the truth with such measure of boldness and faithfulness as was given me. Some of my friends at the chapel thought that the people would have molested me, but no one offered to injure me by word or action, and I came safe out from among them." He also writes: “——is, I fear, something like the robin spoken of in 'Pilgrim's Progress, who can eat sometimes grains of wheat and sometimes worms and spiders. I am quite sick of modern religion; it is such a mixture, such a medley, such a compromise. I find much, indeed, of this religion in my own heart, for it suits the flesh well; but I would not have it so, and grieve it should be so." He preached much at Allington, near Devizes, and in the Metropolis, and many other places. His ministry was attended by crowds, and was blest to saint and sinner. In 1838 he became Pastor of the Churches at Oakham and Stamford, residing in the latter town till failing health caused his removal to Croydon. At the time of his settlement at Stamford he became associated with the "Gospel Standard," and in 1849 he was appointed editor. He was a most interesting writer on the things of God. His sermons are experimental rather than doctrinal, but when he treated of doctrine it was in a comprehensive and scriptural way, as his "Meditations" amply prove. His book on "The Eternal Sonship" practically closed the controversy which gave it birth. His "Reviews" are most instructive and brilliantly written. Would that the younger members of our Churches made a study of them! "The Advance of Popery" was another work which had a wide circulation, and events today prove the accuracy of the forecasts so solemnly made therein. His "Letters" have been a means of grace to many, and it is refreshing through them to know the spiritual history of some of the excellent of the earth in their day and generation, and to have glimpses of services at Eden Street, Gower Street, and Great Alie Street Chapels, and at Came and other places, especially in Wiltshire.”

Joseph Philpot's Letters

Joseph Philpot's Sermons