Often Do I Seriously Doubt Whether I Was Ever Converted At All

February 1, 1834

My dear Joseph Parry,—I have been partly prevented from answering your letter earlier by a painful inflammation of the eyes, which has been upon me this last fortnight, off and on, and is not yet subsided.

I could wish I could give a more satisfactory answer to it than I fear you will find this to be. But my own mind is very dark, and the arm of the Lord is not yet revealed to me. The affair which I communicated to you went off more quietly than I had expected. Either the bishop was not applied to, or did not think it worth while to interfere. While that matter was pending, I was quite satisfied to leave it in the hands of the Lord, and was indeed more desirous to be removed than to remain. But I felt then, that if it was not to turn me out, it would more settle me than before. And so it has proved, my mind being now less at work upon leaving than it was at the time I saw you. Towards this place and people I can almost say, ‘Reuben, you are my first born; the beginning of my strength.’ And thus I feel unwilling, I may say unable, to leave them without some clear direction in providence or in grace.

And I think, if you knew what a dark, dead, ignorant, lifeless, corrupt creature I was, your desire to see more of me would be much abated. Often do I seriously doubt whether I was ever converted at all, so much darkness, corruption, and infidelity do I find in myself. And as to the ministry, I feel myself more and more unfit for it, as having so little light, life, and power in my own soul, and knowing so little how to deal with the souls of the heaven- taught family. And these, I do assure you, are not the common-place confessions which every one professes to make, but what I really see and feel in myself. And what a grievous thing it is for a church to invite a man to minister for a few weeks, to be satisfied with his gifts and graces, and then find they have saddled themselves with one who knows nothing of the things of God spiritually, and therefore cannot build them up in the experimental truth as it is in Jesus! The people here are ignorant, and do not discern my deficiencies so clearly, perhaps, as I do myself; and as they profess at times to obtain good, I am led on from time to time to preach to them. But, as to leaving them and undertaking a new work in a new part of the vineyard without seeing my way clearly marked out, it is what I dare not do.

At the same time I adhere to what I have long felt and said, that is, that if I had more grace I would not remain in the Establishment. But this very lack of grace, which keeps me in it, would render my ministry unprofitable outside of it. In this day there is too much of the cry, ‘Put me into one of the priests’ offices, that I may eat a piece of bread;’ and as it is like people, like priest, it is not very difficult for a man with tolerable gifts to secure himself a pulpit in a respectable chapel. But I trust this is far from my views and wishes. A minister to be profitable must be sent; and he who is sent will seek the glory of Him that sent him, and will desire, above all things, grace in his soul as a Christian, and grace as a minister, that the work of the Lord may prosper in his hands. And amid all my darkness and corruptions I desire nothing more than to have light, and life, and unction in my soul, both privately and ministerially.

This, then, you must accept as my answer to your very kind letter, that I do not see my way to leave my present post, and that I hope you will not delay on my account to settle over you such a minister as the Lord may send you. But should I come into your parts, and I consider myself at liberty to preach in chapels, and it meets your wishes, I would be very glad to accept your offer of preaching for a Lord’s-day or so. But whether that time will ever arrive, or when it may arrive, I cannot just now say. The Lord will hasten it in His time. He is a Sovereign, and I would willingly see His sovereign hand and hear His sovereign voice directing me in the path wherein I should go. I have not seen Brother Tiptaft for some time, and am inclined to think he must be from home. I do fear he will think this letter unsatisfactory. I feel it to be so myself, but I know not how I can write otherwise. Give my Christian regards to Mrs. Parry, and accept the same from,

Yours very sincerely and affectionately, J. C. P.

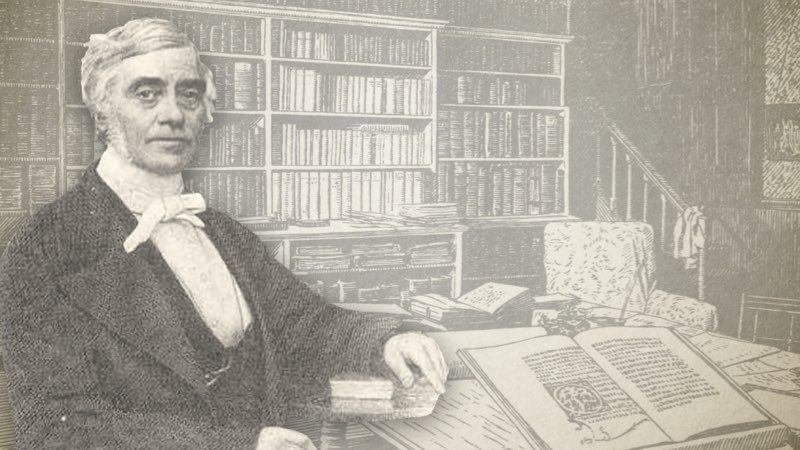

Joseph Philpot (1802-1869) was a Strict and Particular Baptist preacher. In 1838 he was appointed the Pastor of the Churches at Oakham and Stamford, during which time he became acquainted with the Gospel Standard. In 1849, he was appointed the Editor for the Gospel Standard Magazine, a position he held for twenty-nine years (nine years as joint Editor and twenty years as sole Editor). John Hazelton wrote of him—

“A man of great grace, profound learning, and with a literary style equal to any of his contemporaries. For twenty years he was editor of the "Gospel Standard," in which his New Year's Addresses, Meditations, Reviews, and Answers to Correspondents were outstanding features. His ten volumes of sermons, entitled "The Gospel Pulpit," and his four volumes of "Early Sermons," testify to his powers as an expositor of the Word, to the beauty of his illustrations, and the heart-searching character of his ministry. He was born at Ripple, Kent, where his father was rector, and educated at Merchant Taylor's and St. Paul's schools, entering at Oxford University in 1821, taking a first-class, and ultimately becoming Fellow of his College. He accepted an engagement in Ireland as a private tutor, but prior to his departure he was unexpectedly detained at Oakham. There he bought a book, "Hart's Hymns," and was much struck by the beauty of many of them. In 1827, in Ireland, eternal things were first laid upon his mind, and "I was made to know myself as a poor lost sinner, and a spirit of grace and supplication poured out upon my soul." He returned to Oxford in the autumn, and "the change in my character, life, and conduct was so marked that everyone took notice of it." Early in 1828 he was appointed to the perpetual curacy of Chislehampton, with Stadhampton—or Stadham—not far from Oxford. He soon gained the love and esteem of his parishioners. His Church was thronged, and his labours were unceasing amongst young and old. In 1829 he became acquainted with William Tiptaft (1803-1864), vicar of Sutton Courtney, and a friendship commenced which death alone severed. Both ministers had been led to know the truths of predestination and election and the final perseverance of the saints, and preached them with unflinching boldness. Persecution soon arose; it always does in some quarter when there is a faithful ministry. In 1831 Tiptaft built a chapel at Abingdon, where he remained as a Baptist pastor until his death. In 1835 Mr. Philpot resigned his living and his fellowship; the temporal sacrifice entailed was such that he had to sell almost all his books. Soon after this momentous step had been taken he preached in a chapel at Newbury, which some of his friends had procured for the purpose. He writes: "When I therefore began to open up that God had a chosen and peculiar people the whole place seemed in commotion. One man called aloud, 'This doctrine won't do for me!' and started out, and was instantly followed by five or six others. I was not, however, daunted by this, but went on to state the truth with such measure of boldness and faithfulness as was given me. Some of my friends at the chapel thought that the people would have molested me, but no one offered to injure me by word or action, and I came safe out from among them." He also writes: “——is, I fear, something like the robin spoken of in 'Pilgrim's Progress, who can eat sometimes grains of wheat and sometimes worms and spiders. I am quite sick of modern religion; it is such a mixture, such a medley, such a compromise. I find much, indeed, of this religion in my own heart, for it suits the flesh well; but I would not have it so, and grieve it should be so." He preached much at Allington, near Devizes, and in the Metropolis, and many other places. His ministry was attended by crowds, and was blest to saint and sinner. In 1838 he became Pastor of the Churches at Oakham and Stamford, residing in the latter town till failing health caused his removal to Croydon. At the time of his settlement at Stamford he became associated with the "Gospel Standard," and in 1849 he was appointed editor. He was a most interesting writer on the things of God. His sermons are experimental rather than doctrinal, but when he treated of doctrine it was in a comprehensive and scriptural way, as his "Meditations" amply prove. His book on "The Eternal Sonship" practically closed the controversy which gave it birth. His "Reviews" are most instructive and brilliantly written. Would that the younger members of our Churches made a study of them! "The Advance of Popery" was another work which had a wide circulation, and events today prove the accuracy of the forecasts so solemnly made therein. His "Letters" have been a means of grace to many, and it is refreshing through them to know the spiritual history of some of the excellent of the earth in their day and generation, and to have glimpses of services at Eden Street, Gower Street, and Great Alie Street Chapels, and at Came and other places, especially in Wiltshire.”

Joseph Philpot's Letters

Joseph Philpot's Sermons