Faithfulness unto Death

Preached at North Street Chapel, Stamford, on Lord’s Day Morning, Dec. 8, 1861

These words which, as uttered by my voice, are still sounding in your ears, form a part of the message sent by the Lord Jesus Christ through his servant John to the angel of the church of Smyrna. This, I need not tell you, was one of the seven churches in Asia to which special messages were addressed by the Lord Jesus when he appeared to John in the Isle of Patmos. In that lonely isle, whither John had been banished “for the word of God and for the testimony of Jesus Christ,” he had a glorious vision of the Son of God, and by him was bidden to write to the seven churches. It is the opinion of some learned, and, I may add (which is of greater authority), of some gracious interpreters of God’s word—I need only mention among the latter as a proof of my assertion the revered names of Dr. Gill and Mr. Huntington— that these seven churches of Asia Minor have a prophetical aspect; in other words, that they represent seven church states which were to intervene between the apostolic age and the consummation of all things, when our Lord shall come a second time without sin unto salvation. I shall not occupy much of your time in stating the various arguments used to establish this position, more especially as it is not one much commended to my conscience. But they view it thus. They argue that as the Revelation is wholly a prophetical book, it would be very strange and unsuitable to its title if the three first chapters contained in them nothing prophetical; that the glorious appearance of Christ to introduce these messages seems scarcely necessary to send messages to a few particular churches; and that promises are contained in them which seem of a more prophetical and spiritual character than could fairly belong to these assemblies of the saints, some of which were very small and most of which soon passed away. You will observe that I am merely stating their arguments, not my own, and I am bound to say that, though far from conclusive, there is some force in them. The very names of the churches they consider also to have in them a spiritual significancy. Thus the church of Ephesus, which they consider to signify, at least by allusion, desire, expressive of fervent love, represents the apostolic age; that at Smyrna, which signifies myrrh, the time when the church was suffering oppression and persecution under the Roman Emperors, their patience under their torments breathing forth, like bruised myrrh, a sweet smell of incense; that at Pergamos, which means high and lofty, especially a lofty tower, the rise of the Papal power, for this church dwelt “even where Satan’s seat is,” which we know is proud and lofty Rome with all its abominations. Thyatira, which they understand to mean a daughter, represents, according to their view, the Church’s darkest age, when superstition and idolatry pervaded every nation, and the worship of the Virgin Mary, called by the Romanists “the daughter of God,” prevailed over and was set above the worship of Jesus Christ. Then was truly the reign of “the woman Jezebel,” and the prevalence of the awful “depths of Satan.” Sardis, which may mean precious, as alluding to the precious stone called sardian or sardine (Rev 4:2), represents the time of the Reformation, when Luther and Calvin burst the fetters of the Romish Church and proclaimed salvation through the blood of the cross. We are in the Sardis state now, according to the views of these learned men, and just towards the close of it when the church “has a name that she liveth and is dead.” And yet through sovereign grace there are still “a few names even in our Sardis which have not defiled their garments” with the pollutions of the world or the deep-dyed stains of error; and those shall one day walk with Christ in white, for they are worthy. Then comes the next state, the Philadelphian, which signifies brotherly love, when, according to their view, there will be a large outpouring of the Spirit of God, a day of great prosperity to Zion, a spreading of the Gospel to all the nations of the earth, and the spiritual reign of Christ, when the brethren will love each other, not as now coldly, but with a pure heart fervently. Then comes the Laodicean state, which signifies the judgment of the people, the last and the worst, when the church will have sunk into such a state of lukewarm profession that the Lord will “spew her out of his mouth;” and this will introduce the general judgment when the Lord will sit upon his throne, and men shall be judged according to their works.

Now though this interpretation of the seven churches is very ingenious, and though there may be some degree of truth in it, I cannot say it meets with full acceptance in my mind, and indeed I see great difficulties in it. I prefer, therefore, to take a different view of the whole subject, and laying aside or leaving out of consideration any prophetical aspect that those churches may bear, I choose rather to regard them in a spiritual and experimental point of view. Let me explain my meaning more distinctly. I view these churches, then, as laid naked and bare before us by his eyes which are as flames of fire, and spoken to by his voice which is a sharp two-edged sword, as representing certain evils that manifest themselves from time to time in the visible Church of God. These messages, then, contain rebukes or admonitions from the Lord suitable to the eruption of these various evils, and embrace at the same time peculiar and precious promises adapted to the family of God as exposed to the various temptations incidental to those evils, as well as to support them under their trials, and deliver them out of their afflictions. This view of the subject, which makes every word of these messages instructive at every period of the Church’s history to those who fear God, is, I think, very much borne out by that remarkable appeal which is given at the close of every one of them, “He that hath an ear, let him hear what the Spirit saith unto the churches.” Of one thing I am very sure, that whereas the prophetical view may be but speculative, this is practical; while that may be merely fanciful, this is real; while that at the best is but doctrinal, this is experimental; whilst that is for different times, this is for all times; and whilst that may amuse the mind and instruct the judgment, this searches the heart and reaches into the inmost conscience. Under this point of view I shall, therefore, with God’s help and blessing, attempt to handle our subject this morning.

The message of the Lord to the Church at Smyrna has this peculiar character stamped upon it, forming a single exception to the messages directed to the other churches—that there is no rebuke contained in it. Knowing her suffering circumstances, the Lord dealt with her very tenderly. She was in the flames of persecution, and it would seem that a still hotter fire was preparing for her, for some of her members were to be cast into prison. Polycarp, it is generally supposed, was at this time the chief superintendent of the Church of Smyrna, and to him as its angel or messenger was this message most probably sent. He was cast into prison some years afterwards, and then burnt to death, leaving behind him a blessed testimony which is still preserved in church history. The Lord, then, seeing her present affliction and knowing what was about to come upon her, does not rebuke her for any evil that might have been apparent in her, for we cannot think that she was altogether free from fault, but sympathising with her in her afflictive circumstances, rather speaks to her words of encouragement and consolation, as a sustaining cordial for the present and the future.

We may, I think, in looking at our subject from that spiritual and experimental point of view of which I have already spoken, divide it into these four leading features:—

I.—First, an intimation of suffering, “Fear none of those things which thou shalt suffer.”

II.—Secondly, a gracious admonition not to be daunted by any suffering that might come upon her. “Fear none of those things.”

III.—Thirdly, an exhortation to faithfulness under all circumstances, and to the very last. “Be thou faithful unto death.”

IV.—Fourthly, a blessed promise of an eternal inheritance: “I will give thee a crown of life.”

I.—Suffering, in one shape or another, is the appointed and therefore the universal lot of the Church of Christ. It was the way in which her Head preceded her as a man of sorrows; and as we are to be conformed to the suffering image of the Son of God here, that we may be conformed to his glorified image hereafter, every member of his mystical body must fill up his appointed portion of afflictions. The apostle, therefore, speaking of himself, says, “Who now rejoice in my sufferings for you, and fill up that which is behind of the afflictions of Christ in my flesh for his body’s sake, which is the church.” (Col 1:24) These are remarkable words, but have a deep spiritual and experimental meaning. The apostle does not mean that there was any deficiency in the meritorious and vicarious sufferings of the Lord Jesus Christ which he could complete; but his meaning is, that there was a certain measure of suffering appointed to him as a member of the mystical body of Jesus which he was to fill up. We gather, then, from these words that a certain amount of suffering is allotted to the mystical body of Christ as well as to its suffering Head; so that when all the members of this mystical body shall have filled up each his appointed portion, then the whole amount of predestinated suffering will be complete, and every member will then have been conformed, according to his appointed measure, to the suffering image of our gracious Lord. Are we not expressly told, “If we suffer we shall also reign with him” (2 Tim 2:12); and again, “If so be that we suffer with him that we may be also glorified together?” (Rom 8:17) And does not the apostle speak of suffering as a peculiar privilege: “Unto you it is given in the behalf of Christ not only to believe on him but also to suffer for his sake?” (Phil 1:29) So deeply were the apostles of the Lord penetrated with this truth that when they had been beaten they “departed from the presence of the council, rejoicing that they were counted worthy to suffer shame for his name.” (Acts 5:41) If, then, you are a sincere follower of the Lord the Lamb, lay your account with suffering: it is a mark impressed upon every member of Christ’s mystical body, what we may call the sheep-mark of the flock of slaughter. (Zech 11:7)

1. But this suffering assumes various shapes and forms. The Lord, who is full of infinite wisdom as well as goodness and mercy, deals out to every member of his mystical body not only that measure which seems good in his eyes, but also that peculiar mode of suffering which he sees is most conducive to its good and redounds most to his own glory. But taking a general view of the sufferings of the saints of God, we may divide them into two grand branches: the sufferings of the body and the sufferings of the soul: those sufferings which are temporal and natural, and those sufferings which are peculiarly spiritual and experimental. Not but what all their suffering is in a measure spiritual and experimental, because the blessed Spirit makes use of every kind of suffering to work thereby the good pleasure of his will. But, taking a general view of the subject, we may divide the sufferings of the saints of God into two grand branches—temporal and spiritual.

(1) Persecution is one mode of suffering with which the Lord has seen fit in all ages to exercise his afflicted people. It was especially so in the times when the scriptures were written, and more so after the canon of Scripture was closed, during the persecutions of the Roman Emperors. It is true that in our day persecution has lost much of its force. Martyrs are no longer burnt in Smithfield flames, and prison doors no longer open that the saints of God may be immured in their lonely cells. But though persecution, through the advance of civilisation and the general feeling of humanity and liberality, is muzzled as to open violence, yet the enmity of the human heart against the saints and the truth of God remains unextinguished and inextinguishable; for if the carnal mind is at enmity against God, it will manifest itself in enmity against those who belong to God and bear the image of God. Therefore, as far as can be manifested, persecution will lift up its head. I have myself in days gone by, especially when I first made a profession of religion, much suffered from persecution. When I was at Oxford as a Fellow of a College, it was especially directed against me, to the entire breaking up of all my worldly prospects, and, could some have had their full liberty, to the stripping me not only of my just due but of everything that I possessed. Since then my persecutions have been not so much from the world as from the professing church. Let me, however, waive this subject, though I feel bound to speak of it for the comfort of those who may have to pass through similar trials. Persecution from the world or from the church never hurt a hair of my head. Here I stand this day more benefited than harmed by it.

(2) But take another form of suffering. Look at the various providential difficulties and trials that all in a measure are subject to. Losses and crosses, with great and sudden reverses in providence, are not limited to one class, the last and lowest in the social scale. They are universal; for providential reverses may and do come upon the rich as well as upon the poor. It is a great mistake to think that none know poverty but the poor. In fact, the contrary is rather the truth. He that has little to lose can lose but little; but he who has much may in a moment lose his all. How many at this moment, who were once in comfortable circumstances, have by the breaking of a bank or some such unlooked-for incident, been cast down in a moment into the very depths of poverty. Those in the middle class of life, who to all outward appearance may seem thriving, often have great reverses in business, unexpected losses, which, in spite of all their care and industry, may sadly cripple their means, if not actually bring them into destitution. And the labouring man, whose capital is his brawny arms and his stout heart, may have his share of providential suffering by being cast upon a bed of sickness, or, as many of the working classes are now experiencing in the North, by being thrown out of employment by dullness of trade or other circumstances. The poor have an idea that none suffer from poverty but themselves. Now my full persuasion is that the class just above the poor, as the small farmer, the little tradesman, the cottager with his few acres of land, and persons of small independent means, are often much more sharply bitten by the tooth of poverty than those who work for wages. But of course I speak of these providential trials as a part and a very large part of the sufferings of those who truly fear God, for with others I have nothing to do; and as the Lord has his people in various classes of society, so he exercises very many of them with these providential trials. In fact it is absolutely necessary that we should experience at some period of our lives some of these providential crosses, losses, and reverses that we may know there is a God in providence, that we may see that side of God’s face as well as his more gracious aspect. It is poverty and more especially losses and reverses in providence that teach us there is a God who has the hearts of all men in his hands; that “the silver and the gold are his, and the cattle upon a thousand hills.” If there were no such reverses or losses, and no such appearance of a kind God in providence, we should, like the world, be either worshipping mammon with all our heart when the wind of success filled our sail, or sink under the storm when adversity beat upon our ship.

(3) Look again at another form of suffering, when the Lord lays his hand upon our earthly tabernacle. How many of the dear saints of God at this moment are stretched upon beds of pain and affliction! The Lord in his infinite wisdom, seems to have special reasons thus to lay his hand upon the bodies of some of the most eminent of his saints, that he may bring them more sensibly down under his chastening hand. Some of the choicest, most highly-favoured, and deeply-taught Christians I have ever conversed with are those who have been most heavily afflicted with bodily sickness, and, in several cases, who have lain for years on a bed of affliction. The Lord has so sanctified their bodily sufferings to their soul’s good; has so fully separated them not only in body but in spirit from the world whilst lying upon their beds of pain and languishing; has been pleased so to draw near to them in sweet communion; so to manifest to them his love and grace, that he has made their bed in all their sickness, and raised up in the lonely hours of the night many a note of praise for his afflicting as well as his consoling hand. I have had myself for many years no small measure of bodily infirmity and at times of severe illness, which has been a daily and sometimes a very heavy cross; but some of the best seasons I have ever enjoyed have been upon a bed of affliction.

(4) Take, again, family afflictions, for while we are in the body we are so closely connected with domestic ties, and they twine themselves so firmly round our heart, that out of the bosom of our warmest affections often spring our sharpest sorrows. How few there are of those who fear God who do not sooner or later drink the bitter cup of domestic sorrows, whether in painful bereavements of husband, wife, or child, or from circumstances arising in the family which are more grievous than death itself. When the grave opens its mouth upon the dear object of creature love, it seems as if that were the heaviest of all family sorrows; but there are afflictions far deeper than those of the grave, especially if the departed one has been laid there with a good hope of rising to glory on the resurrection morn. A profligate husband, a faithless wife, a dishonoured daughter, an infidel son may be a much worse affliction than a buried partner or an entombed child.

But I shall not dwell any longer upon these temporal afflictions, though in God’s mysterious alchemy they are made to work for spiritual good to those who fear his great name. Yet as they are in some measure common to the saints of God with the world at large, I shall rather direct your attention to those spiritual sufferings which none experience but the Lord’s living family. These far exceed all temporal sorrow, for as eternity exceeds time, so that the one is but a drop while the other is an ocean, and as the soul excels the body, the one being mortal and the other immortal, so spiritual afflictions far outweigh the heaviest natural trials. As a proof of this, look at the case of Job, upon whose head such an amount of temporal suffering was accumulated: all his property gone at a stroke; his ten children crushed under the ruins of a falling house; his body afflicted with boils from the crown of his head to the sole of his foot; his wife, who should have been his support and comforter, tempting him to curse God and die. Job, however, bore all those temporal afflictions patiently and submissively. But when spiritual afflictions were added to the weight of these temporal sorrows, when God hid his face, when Satan harassed his soul, and he seemed set up as a mark for the burning arrows of God’s wrath, then he began to curse his day and wish he had never been brought into being. Spiritual afflictions cut so deep from this circumstance that they enter into the very depth of a man’s soul, and seem but a prelude to eternal misery. Here it is that they so widely differ from any amount of temporal afflictions. Assume that you are even now afflicted in the most grievous way with temporal trials, there will be an end to them if eternal life dwell in your bosom. If reduced to live and die within the walls of a union workhouse, death will but transport you to a heavenly mansion when the clods fall over your elm shell in a parish grave. If persecuted by an ungodly world, you will stand before God clothed in white robes and with a palm of victory in your hands, when your persecutors are cast into the depths of eternal woe. If your body is afflicted, it is but for a few weeks, or months, or years, and then you will have a glorious body, without pain, ache, or suffering. Or if your families are the cause of acute trouble, time must remove you from them or them from you. But O! the soul! that immortal principle which must live for ever: this cuts so deep. If this be wrong all is wrong; if this be right all is right. But again how tender and sensitive is the soul compared with the body! The one is flesh, the other spirit; the one a mere mass of bones and sinews, but the other the breath of God; the one to rot and moulder in its native earth, the other to exist for ever in happiness or misery. This is the reason, then, why spiritual troubles cut so deep, because they cut into that which is to live for all eternity; that undying, immortal, unquenchable principle which will exist when time itself shall be no more.

Firstly, look, for instance, at the sufferings of a soul under the first convictions of sin when lying under the curse of a broken law, and trembling under the apprehension of wrath to come. Is not the poor soul almost ready to curse the very day of its birth? How gladly would it be a dog, a bird, a reptile sooner than as a human being to possess an immortal soul and lie for ever under the terrible indignation of the Almighty. Now what are all temporal sufferings compared with the pangs of a guilty conscience, the fear of lying for ever under the burning wrath of God; to be shut up, and that for ever, in that horrible abyss of woe out of which there is no coming; that dark and gloomy abode into which no ray of hope will ever penetrate, and for ever to be surrounded with the company of devils and lost spirits, tormenting and being tormented, hateful and hating with eternal hate? As these gloomy thoughts revolve over the soul, under the first breakings in of light to see and life to feel the guilt of sin, how they swallow up all temporal sufferings as an ocean swallows up a brook.

Secondly, look again at the temptations and fiery darts of Satan, what has been well called the artillery of hell, which he opens with such readiness and plies with such vigour when permitted by the Lord. What, I may ask, are temporal troubles weighed in the scale against Satanic temptations to blasphemy and suicide? If you are persecuted by man, even were you, like the Italian and Spanish converts, shut up in prison or condemned to the galleys for faith in Christ, you might even there, with Paul and Silas with their feet in the stocks, or with John Knox when he was pulling at the galley oar, sing psalms of praise to your God. His presence could illuminate the darkest cell; his love support under the deepest bodily suffering. If reduced to the extremest poverty, were you favoured with a sense of the Lord’s goodness, you might bless God in your lonely garret and water your crust with tears of gratitude. If afflicted in body but supported in soul, you could bless God for a sick chamber. If painful circumstances arise in your family, or the desire of your eyes be taken away at a stroke, you might still be able, in sweet submission to the will of God, to say with Job, “The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away: blessed be the name of the Lord.” Thus under the greatest temporal affliction, the soul may enjoy the peace of God which passeth all understanding. But where are joy and peace, where even calmness of mind and submission of spirit, when fierce temptations roll over your soul and fiery darts burn in your bosom? For these temptations do not come alone; they meet with the corruptions of our nature, and set them all on fire. What then is any temporal affliction compared with the wickedness of the human heart stirred up by the power of Satan, or the awful thoughts even against God himself that pass and repass over the troubled soul?

Thirdly, look again at the doubts and fears in which many of the saints of God are held, and some of them during the greater part of their life. All the family of God do not sink so deep into soul trouble as I have described, nor are all exercised by those grievous temptations as to the being of God, or those blasphemous suggestions and vile imaginations to which I have just alluded. But very many of the family of God who are spared these distressing sorrows are deeply exercised as to their state and standing for eternity, passing their days full of doubt and fear; and thus they go on for years, like Pharaoh’s chariot wheels, driving heavily along through the deep sand sometimes even to a dying bed.

Fourthly, or if you have been blessed in any measure with a sense of God’s goodness and mercy, then to experience the hidings of his face; the darkness of mind that takes place when the light of his countenance is gone; the grievous temptation to doubt and fear whether the whole was not a delusion; the painful retrospect of having neglected so many opportunities which the Lord gave when he indulged you with nearer access to himself, and seemed to hear your prayer almost before it was uttered. What temporal afflictions are equal to the hidings of God’s face?

Fifthly, again, look at the guilt of backsliding; the sorrows and troubles which many of the saints of God have to wade through from being overcome by the power of sin and entangled in the snares of Satan. Guilt of soul, from a sense of backsliding, cuts more deeply into the conscience and is a source of far acuter grief and sorrow than the first convictions of sin. Surely to sin against light and conscience, against goodness and mercy, against love and blood, is a transgression of a far deeper dye, of a much blacker hue, than to sin in ignorance, in carnality, in death. How the sin of David was aggravated by the Lord’s mercies, and how the Lord reminded him of this by Nathan when he told him, “I anointed thee King over Israel, and I delivered thee out of the hand of Saul.” “Wherefore hast thou despised the commandment of the Lord to do evil in his sight.” (2 Sam 12:7, 9) It is sinning against the Lord’s goodness and mercy which so aggravates the sin of backsliding, and it is the producing guilt of conscience which makes a sense of those slips and falls to be more heavy and acute than that felt in the first application of the law.

2. But if we look a little more closely into our text we shall find in it an intimation that some of the saints at Smyrna would have to pass through a peculiar trial; and, viewed in a spiritual and experimental sense, we may find in this something applicable to the state and case of the family of God now. “Behold, the devil shall cast some of you into prison, that ye may be tried.” This in their case was true literally; not that the devil could take them by the neck and hurl them into prison under a bodily shape. But he cast them into prison by instigating those to do so in whom the power was lodged. He worked upon the prejudices and passions of the mob; he stirred up the enmity of the Roman governor; he insinuated lies and calumnies against them into the mind of the priests of the false worship then prevalent in Smyrna; and thus, though he himself put forth no hand, he instigated those to do it who had the power. I have already intimated that there might have been some intimation here of the imprisonment and martyrdom of Polycarp, who was at this time over the church at Smyrna. But whether so or not, and I by no means wish to speak of it with any degree of certainty, the devil was to cast some of them into prison, not for their destruction, but that they might be tried. Prisons now are shut upon us. No Bedford gaol takes in another Bunyan. No soldiers are standing at our chapel door to carry me off to prison, as would have been the case had I stood up here 200 years ago. We have neither Bedford gaols nor have we Bunyans now. In losing the one we have lost the other. Not that I wish to see the interior of a prison for righteousness’ sake, for that would soon close my earthly career. But there is a spiritual prison into which the devil is permitted at times to cast some of the saints of God. As he was the instigator of the mob who cast Polycarp into prison, so he can instigate the baser and more furious mob of our own blind passions and corrupt affections, and then, as the consequence of the commission of sin, afterwards cast us into the prison of a guilty conscience. Are you never in prison? Is not this sometimes your melancholy cry, “I am shut up and I cannot come forth?” Is there no bondage ever over your spirit; are there no fetters ever around your limbs? When you come to the throne of grace, when you bend your knee before the majesty of heaven, when you assemble yourselves in the house of prayer, is it all freedom, holy boldness, filial confidence, and sweet access unto the Father? Is there never any groan or lamentation over hardness of heart, deadness of affection, and that miserable bondage which shuts up your soul almost in the condemned cell? And why is this? You can see there was a cause; that Satan, by working upon your corrupt affections, has entangled you in some snare. And what has been the consequence? You have been cast into the gloomy gaol, and there, like Samson, with your eyes put out, you are grinding and groaning in the prison-house.

3. But why this? That you maybe shut up for ever in the prison of hell? that this present darkness and gloom should be but the prelude to eternal woe, to the blackness of darkness for ever? that like a man to be hanged to-morrow, you are now shut up with bolts and bars, to be taken out of the condemned cell to be made a public exhibition, and then to be gibbeted for ever, as a monument of God’s awful displeasure? No; that is not God’s purpose in letting you go to prison; but “that you may be tried;” that every grace of the Spirit in you may be proved as by fire whether it be of God or man, that your faith may be tried and proved to be genuine; that your hope may be tried and found to be a good hope through Christ; that your love may be tried if it be feigned, or whether you will love the Lord in spite of his desertion of you and the hidings of his face; that your patience, your perseverance in well doing, your endurance to the end, your repentance and godly sorrow for sin, your humility, spirituality of mind, separation from the world, your crucifixion of the flesh, and holy determination to cleave to the Lord with purpose of heart, may all be tried. The prison, the gloomy cell, the darkness under which you labour, the struggles for deliverance, the fear that you may never come out—all these things will try you to the uttermost; but by them it will be made manifest if you are a true saint of God and whether the work upon the conscience is genuine. We think it hard to be so often in prison; and yet how the prison tries the graces of God’s people! How it makes them look and examine to see whether the root of the matter be found in them! How completely it puts a stop to all creature boasting! How it makes them long for deliverance! How it whets the edge of their appetite for the promises, for the application of atoning blood, for the discovery of salvation, for the revelation of Christ, and for the manifestation of his dying, bleeding love! How it stirs up prayer and supplication in their breast! How it makes them look and long for the Lord’s appearing, so that they can say with David, “As the hart panteth after the water brooks, so panteth my soul after thee, O God” (Ps 42:1); and again, “I wait for the Lord: my soul doth wait, and in his word do I hope. My soul waiteth for the Lord more than they that watch for the morning.” (Ps 130:5, 6) Thus their mournful cell is made to them a place of most blessed profit, for in their prison they are tried, and when tried they come forth, as Job said he should, as gold. Was not this the Lord’s special mission “to bring out the prisoners from the prison and them that sit in darkness out of the prison house?” (Is 42:7) Was he not specially anointed and sent “to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to them that are bound?” (Is 41:1) O, how many of the Lord’s dear family are shut up in the prison house out of which they cry, “Let the sighing of the prisoner come before thee” (Ps 79:11); and how the Lord “looks down from the height of his sanctuary to hear the groaning of the prisoner, to loose those that are appointed to death.”

4. But there is another feature which I cannot pass over, for it seems to cast a light upon the whole of the path of suffering in which the Lord’s saints tread. “Ye shall have tribulation ten days.” These ten days are supposed by some interpreters to signify the ten persecutions under the Roman Emperors, or the ten years of the last persecution under the Emperor Diocletian. Whether such be the right prophetical interpretation of the passage or not I will not attempt to decide, for on these points I have very little light. I prefer a spiritual, experimental interpretation, as not only much surer and safer, but much more profitable. I consider, therefore, the “ten days” to signify a certain definite period, not strictly ten days either as measured by the rising and setting of the sun, or by understanding days for years, but a space of time fixed in the mind of God. I gather, then, from these “ten days,” as the fixed limit of the suffering of the church at Smyrna, this sweet inference, that the Lord has appointed a certain bound to all the tribulation which his people shall endure; that as he determined the church at Smyrna should suffer ten days or ten years, if such be the mind of the Spirit, so he has fixed tribulation as the lot of his people to be endured only for a certain period. As, then, when those ten days were run no tribulation could hold the prisoners at Smyrna fast, so when the saints of God have filled up each the appointed measure of suffering, then their tribulation will come to a close.

Look at this in a spiritual point of view, and compare it with the variety of suffering that I have brought before your notice. You are now suffering persecution: it is but for a time; there are only ten days of persecution for you. You are afflicted in providence; you have great reverses; you have losses in business; you have bad debts; you are reduced to a measure of destitution, and are trembling and fearing what will be the consequence. It is only for ten days; there is an appointed time when there will be a change for the better, and providence will once more smile. You are suffering in body; you have an afflicted tabernacle; you are often brought down by sickness; scarcely know a day’s thorough health; it is but for ten days. If those days spread themselves to the end of your life, still it is but a few days compared with eternity, and we may say of it what Rebekah’s mother and brother said of her, “Let the sickness abide with us a few days, at the least ten; after that it shall go.” (Gen 25:55) Or these ten days may be for ten weeks only, or only ten literal days, and then your illness may be turned into health. So of family afflictions, the hidings of God’s face, the temptations of Satan, bondage, and imprisonment, and all the various modes of suffering which I have run through, all are but for a limited time; God has fixed the exact period when they shall come to a close; and thus we see that tribulation itself, like the sea, may loudly roar, but has certain bounds which it cannot pass.

II.—But this leads us to our second point, which is the gracious admonition that the Lord speaks by John to the church at Smyrna, not to be dismayed at affliction and trouble; “Fear none of those things which thou shalt suffer.” It is as if the Lord said to the church at Smyrna, “Look at the things which thou shalt suffer; examine them well; take a clear and full view of them; draw up a catalogue which shall contain every item; consider them one by one; cast up the whole amount; look at them singly and wholly fairly in the face, and when thou hast taken this deliberate survey of them, let this be the feeling of thy heart, Fear none of them.” “But we do fear, Lord! Our flesh is cowardly; we shrink from the fire; we cannot bear suffering; it is so painful, so trying, and we are so weak; O, if it be possible let this cup pass from us.” But the Lord replies, “Fear none of those things which thou shalt suffer.” Your fears are groundless; your apprehensions have not any solid base upon which to rest. I tell you again, “Fear none of those things which thou shalt suffer.” I do not say, Fear not some, but I say, “Fear none.”

But let us, with God’s help and blessing seek to dive a little deeper into the meaning of this gracious admonition, and seek out what spiritual reasons there are why we are not to fear.

1. First, then, none of those things which we shall suffer, if we are indeed the Lord’s, will be able to separate from the love of God. Was not this the apostle’s bold and noble challenge to all modes of suffering, as if he bade them come forward and do their worst? When he had given a catalogue of all the sufferings that God’s people can endure, he then adds, “I am persuaded that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (Rom. 8:38, 39.) Now if none of these things shall be able to separate those who are bound up in the bundle of life with the Lord the Lamb, from the love of God; if tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword, are all powerless to separate, may we not give full credit to the Lord’s own words, “Fear none of those things which thou shalt suffer?” No; they shall never separate thee from the love of God if ever it has been shed abroad in thy heart; they shall never be permitted to overwhelm thee, if indeed thou hast a living faith in the Son of God. Be they temporal or spiritual, ever so high, or ever so deep, they shall never separate thee from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord, for that like himself is eternal and unalterable. Therefore, fear none of them.

2. But again, take another reason, why you should not fear any suffering. The Lord will support you under them. His own promise is, “As thy days, so shall thy strength be.” A sweet assurance and a blessed experience of this made the apostle Paul glory in his infirmities that the power of Christ might rest upon him; for the Lord himself assured him, “My grace is sufficient for thee, for my strength is made perfect in weakness.” (2 Cor 12:9) If, then, the Lord’s grace is sufficient for thee; if his strength is made perfect in thy weakness, “fear none of those things which thou shalt suffer.” Let them come in any form they may, persecution, losses in business, reverses in providence, poverty and destitution, afflictions of body, troubles in the family, nay the very hidings of God’s face, and fiery darts of the devil, and any or every spiritual affliction that may be heaped upon thy head: “fear none of those things which thou shalt suffer;” none of them, none of them shall harm thee. Why need, then, thy heart sink under their prospect or under their reality? If strength shall be given thee according to thy day; if the grace of Christ is sufficient for thee, and if his strength is made perfect in weakness, why need you fear them? If these troubles only bring you nearer to Jesus; if they are made means in the Lord’s hands of drawing ampler supplies of grace and strength out of his fulness; if you learn thereby more of his sustaining power, and see deeper into his sympathising heart, they are not your enemies, but your best friends; for his blood and righteousness, his finished work, death, and resurrection have taken the sting out of every affliction. For what is that sting? Punishment. There is this difference between afflictions coming upon the world and afflictions coming upon the church. Afflictions upon the world are angry punishments; afflictions upon the church are merciful chastisements. As Jesus, then, when he died took the sting out of death, so that the dying saint can say, “O death where is thy sting?” so when Jesus suffered, he took the sting out of affliction; and as by dying he turned death into life, so by suffering he turned affliction into profit.

3. Take, therefore, another reason why we should not fear any of those things which we may suffer; these afflictions will all work together for our spiritual good. Do we not read that all things work together for good to those that love God? Thus, then, our affliction will work together for good; for surely among the “all things” sufferings must be included. As in some beautiful piece of machinery, say, the watch which you carry in your pocket, wheel works into wheel, and all for one definite end, to tell you the correct time of day; so it is with the afflictions, trials, and temptations which befall the church of God; they all work with and into one another in a mysterious manner for the good of the soul. It is true that we cannot see how they work to this end. Is it not so naturally? We might see a piece of beautiful machinery and not understand why one wheel moves in this direction and another in that; why there are cogs here and cogs there; why the wheels are of a different size and in different positions; but if we observe a definite result, and find that our watch keeps time to a minute, we believe, though we may not see, how every wheel and cog was necessary, and that the whole was put together with the most consummate skill. You see on every side beautiful patterns. The dress which you wear or the walls of your house present to your eye a definite and perhaps a beautiful pattern; but you could not explain how a machine could be so contrived as to print it so beautifully in all its various colours; yet you know that it is so. So it is as regards the soul. When the beautiful pattern comes out, the image of Christ stamped upon the heart; when we see in others or feel in ourselves any measure of conformity to the suffering likeness of the Son of God, then we can believe, though we may not understand or be able to explain, how troubles and temptations, sorrows and afflictions, have all been so working together with the Spirit and grace of God, as to bring out that resemblance to the image of Christ which is the glory of the church here below. Do you not long to be conformed to Christ’s image? Is not this your desire and prayer? Then fear none of these things which thou shalt suffer, if they be a means of your prayer being answered.

4. But take another reason why you should fear none of those things which you shall suffer, which will close this part of the subject; they will all work for the glory of God. God is glorified in the sufferings of his saints. By their patience under them, their humility in acknowledging that they deserve them, their submission to his holy will, and especially by the display of his wonderworking hand in bringing them out of all their troubles, and giving them the victory over all their afflictions, a revenue of glory redounds to his great and worthy name. The apostle thus sought to encourage those who were suffering for Christ’s sake, “If ye be reproached for the name of Christ, happy are ye; for the spirit of glory and of God resteth upon you; on their part he is evil spoken of, but on your part he is glorified.” (1 Pet 4:14) And is not that worth suffering for, that you may contribute to the glory of God; that you may endure whilst upon earth the will of God, and be the means of adding to the harvest of praise which is to be reaped one day in the mansions of the blessed? Well may the Lord, then, bid his suffering church to fear none of those things. If none can separate her from the love of God, if support is given her under all them, if all shall work together for her good, and the glory of God shall be the final result, well may Jesus say to the Church, “Fear none of those things which thou shalt suffer .”

III.—But I pass on now to the Lord’s exhortation, and a most blessed exhortation it is. The Lord lay it with power upon your heart and mine! “Be thou faithful unto death.” What is the cogency and pertinency of this exhortation here? Suffering has a tendency to make us unfaithful; therefore, we need the Lord himself to lay this exhortation with power upon our heart, that we may not give place to the tempter.

1. Say, for instance, that you were called upon to suffer. Say that I, like my namesake, was called upon to suffer for Christ’s cause and be burnt, as John Philpot the martyr, in Queen Mary’s days, was at the stake: should not I need special grace to make and keep me faithful to my views of divine truth, to my experience of the power of God, to the doctrines I have preached so long, and for so many years so firmly held? Should I not need the same grace as was bestowed upon that martyr whose name I bear and whose examinations and confession of faith are so well recorded in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, that I might be faithful unto death as he was? Who knows how we should stand if persecution roused up the slumbering flame? I know that I am weak as water and should sink and faint, unless held up by Almighty power.

Or again, look at the various troubles and afflictions which I have laid before you, such as losses in providence, affliction of body, family trials; and besides these external afflictions, the long catalogue of spiritual troubles, such as temptations, the hidings of God’s face, the assaults of Satan, and the mournful despondency of a despairing heart: how we need faithfulness to carry us through this scene of trouble and woe, for how they all foster a murmuring spirit and a giving up in the hour of trial!

(1) The word “faithful” here has two senses. First, it means believing, as the word in the original is often rendered in the New Testament; as in the passage, “Be not faithless, but believing” (Jn 20:27); and again, “They that have believing masters.” (1 Tim 6:2) We may, therefore, read it thus: “Be thou believing unto death.” Thus we are bidden never to give up our faith, never to cast away our confidence, but still to believe whatever may arise; in the dark as well as in the light, when sense, nature, and reason all fail, and nothing remains but the pure word of truth. If ever the Lord has blessed me with a living faith in his name and I have embraced him in the arms of a living faith and affection, I am never to let him go, but believe in spite of unbelief. I am still to repose my soul upon his faithfulness, still to hang upon his promise, and still, as Hart says, to “credit contradictions.”

Whatever sin or Satan or unbelief may suggest, I am still to believe in spite of all the powers of earth and hell. This is the fight of faith; this is how the believer comes off victorious. And this does not depend upon the measure, but upon the nature of our faith. If I have but weak faith I must no more give up that than if I have strong faith; if I have but little hope I must no more part with that than a great hope; for though it be little, if of grace, it is good. A large ship needs a large anchor; but a little boat must have its anchor too; and the little anchor will hold the little boat as much as the large anchor the large ship. But this faith must be maintained by the same power that gave it, and that, too, in the means of God’s appointment. We cannot expect to have this faith in vigorous exercise unless we use those special means which the God of all grace has provided, such as earnest and continual prayer and supplication, reading and searching the word of truth, meditating upon the works of God’s hands, deep and sincere attention to the preached word, and, as furnished with them, the ordinances of God’s house. These are certain means that God has put into our hands whereby faith is maintained in lively exercise. If I am to be faithful or believing unto death, I must not neglect these means to keep me so. I must not go into battle without my rifle. I must not face an invading foe and leave my arms at home. And how am I to shoot with any certainty of hitting the mark unless I practise? How am I to wield the sword of the Spirit if I have never been taught, or, having learned, have by disuse, forgotten the broadsword exercise? No, we are not called upon to play but fight; not merely to appear upon parade, but go when called into the thickest of the battle. I am to pray and meditate and strive in spite of everything opposed to my faith, and thus be believing unto death itself.

(2) But the word means, as rendered here, faithful as well as believing. All Christians are called upon to be faithful. I as a minister must be, above the measure of private Christians, faithful; for it is expected in stewards that a man be found faithful. I of all men am called upon to be faithful—faithful to the ministry, faithful to the office into which I hope God has put me, faithful to the people amongst whom I labour, faithful to my position in the Church of Christ, as contending by my pen as well as by my tongue for the truth as it is in Jesus. And how faithful, whether I or you?

Firstly, we must be faithful to the light that God has given us. If God has given us light, it is that we may be faithful to it; not to hide our candle under a bushel, but hold it up that men may see its beams far and wide. The apostle tells the Philippian believers that they shine or should shine in the midst of “a crooked and perverse generation as lights in the world.” (Phil 2:15)

Secondly, be faithful also to what God has written with his own hand upon the tablets of conscience. Never fight against conscience, never resist the inward dictates of the fear of God, nor sin against the admonition of his Spirit within; but whatever the fear of God prompts you to do, do it, and do it thoroughly; and what the fear of God bids you shun, avoid it and avoid it wholly. Be faithful to God’s vicegerent, an enlightened, a tender conscience, which he has placed in your breast as a witness for himself.

Thirdly, be faithful also to any promise which he has ever given you, to any admonition he has ever applied to your soul, or to any precept he has brought with power into your heart. And remember however difficult it may seem to be to carry these things out, that the Lord’s grace is sufficient for you; and be assured that we can have no real or solid comfort except in proportion to our faithfulness. How could I, for instance, if I had a spark of godly fear in my bosom, after my Lord’s day’s labours, lie down upon my pillow with an easy conscience to-night if I knew that I had been unfaithful through the day; if I had been deceiving the people by erroneous doctrine or false experience, and thus flattering souls into hell? So we all who desire to fear God must be faithful according to the various positions which we are called in the providence and grace of God to occupy. You as hearers are as much bound to be as faithful in your position as I am in mine. You are not to call upon me to be faithful, and then you yourselves neglect the very thing you call upon me to exercise, and for the want of which you would severely and that justly condemn me. You, in your respective positions, are to be faithful to the light that God has given you, to the admonitions of his Spirit in the word and in your conscience, to the profession that you make of his name, to the hope that you have of eternal life, to your fellow believers, and, I may add, to your fellow men. For ye are witnesses for God, as the Lord hath said, “Ye are my witnesses” (Isai. 43:10); and you know God’s own testimony that “a faithful witness will not lie,” and that “a true witness delivereth souls, but a deceitful witness speaketh lies.” (Prov 19:5, 25)

2. And that “unto death.” There is to be no intermission in this warfare. The time is never to come when you may be a little unfaithful, when you may allow yourselves for a short time to be carried down the stream, when you may indulge yourselves for an hour or two in trifling with sin, or let the devil for a little while put his chain round your neck. May a wife be a little unfaithful to her husband? Then may you be a little unfaithful to Christ. There is then to be no cessation of arms, no truce with sin and Satan, no yielding, no surrender. “War to the knife” must be your motto. You must die with the sword in your hand; and fight to the last gasp. Just as our brave soldiers will go on fighting when they have received a mortal wound, so it must be with the faithful soldiers of Jesus Christ. They must die believing, as well as live believing, resist Satan to their last breath, and lay firm hold of Jesus up to the last gasp.

IV.—Then comes our fourth and last point, the sweet promise from the Lord’s own mouth to all who thus faithfully live and faithfully die. “And I will give thee a crown of life.” This promise of an immortal crown is an allusion to the ancient practice of crowning the successful runner in the foot-race with a crown of leaves. The Lord uses this figure as one well known at the time, and gives it a spiritual meaning. But what is “a crown of life?” Why, life eternal; a life of glory in the mansions of ineffable bliss. The faithful warrior has not his reward, at least, not his visible reward, in this life. He must die to have it. As our blessed Lord himself passed through the sufferings of death to win his eternal crown, so must his believing followers. But even in this life the Lord is sometimes pleased to stretch forth this crown as with his own hand from the heights of heaven, that his dying saints may see it as with believing eyes before it is for ever put upon their head. This Paul saw and felt when he uttered the words, “For I am now ready to be offered, and the time of my departure is at hand. I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith: henceforth, there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge, shall give me at that day.” (2 Tim 4:6, 7, 8) Nor is Paul the only saint of God who has had this blessed assurance. In fact, what else can cast the light of heaven upon a dying bed?

How cheering then are these words to the poor, tried, tempted saint of God, who is pressing on through innumerable difficulties, to believe there is a crown of life to be put upon his head, that he shall see Jesus as he is without a veil between, that he shall enjoy a glorious and unfailing immortality in the immediate presence of God, where sin and sorrow are unknown, where tears are wiped from all faces, and there will be nothing but one uninterrupted song of eternal bliss. This is at best but a dying life. What enjoyments we have here are but transient. The sweetest comforts—how soon they vanish away! The happiest frames—how quickly they pass away, and what a blank they leave behind! But heaven when it comes with all its glories will be for ever and ever. There will be no cessation to the eternal happiness which will then be the portion of all the saints of God, but one undying song. To praise and bless the Lord will be the unceasing joy as well as the unceasing occupation of the glorified members of the mystical body of Christ. The Lord, if it be his infinite mercy, set these things upon our heart, and give us that faithfulness unto death whereby he who has graciously revealed the promise will surely perform it, and give us a crown of life!

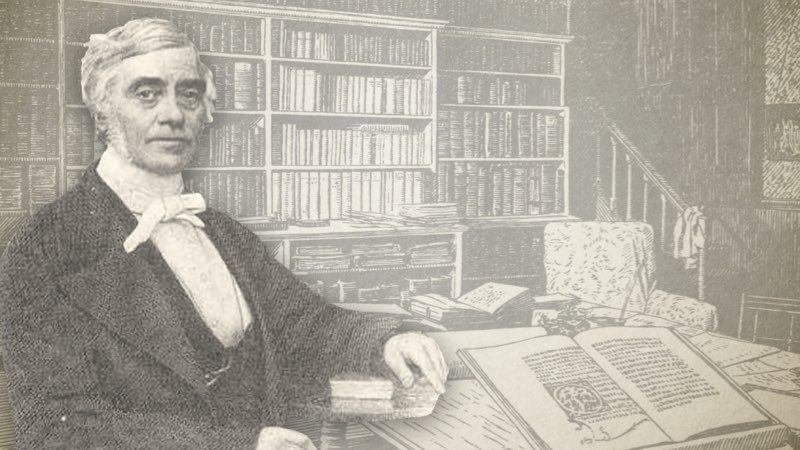

Joseph Philpot (1802-1869) was a Strict and Particular Baptist preacher. In 1838 he was appointed the Pastor of the Churches at Oakham and Stamford, during which time he became acquainted with the Gospel Standard. In 1849, he was appointed the Editor for the Gospel Standard Magazine, a position he held for twenty-nine years (nine years as joint Editor and twenty years as sole Editor). John Hazelton wrote of him—

“A man of great grace, profound learning, and with a literary style equal to any of his contemporaries. For twenty years he was editor of the "Gospel Standard," in which his New Year's Addresses, Meditations, Reviews, and Answers to Correspondents were outstanding features. His ten volumes of sermons, entitled "The Gospel Pulpit," and his four volumes of "Early Sermons," testify to his powers as an expositor of the Word, to the beauty of his illustrations, and the heart-searching character of his ministry. He was born at Ripple, Kent, where his father was rector, and educated at Merchant Taylor's and St. Paul's schools, entering at Oxford University in 1821, taking a first-class, and ultimately becoming Fellow of his College. He accepted an engagement in Ireland as a private tutor, but prior to his departure he was unexpectedly detained at Oakham. There he bought a book, "Hart's Hymns," and was much struck by the beauty of many of them. In 1827, in Ireland, eternal things were first laid upon his mind, and "I was made to know myself as a poor lost sinner, and a spirit of grace and supplication poured out upon my soul." He returned to Oxford in the autumn, and "the change in my character, life, and conduct was so marked that everyone took notice of it." Early in 1828 he was appointed to the perpetual curacy of Chislehampton, with Stadhampton—or Stadham—not far from Oxford. He soon gained the love and esteem of his parishioners. His Church was thronged, and his labours were unceasing amongst young and old. In 1829 he became acquainted with William Tiptaft (1803-1864), vicar of Sutton Courtney, and a friendship commenced which death alone severed. Both ministers had been led to know the truths of predestination and election and the final perseverance of the saints, and preached them with unflinching boldness. Persecution soon arose; it always does in some quarter when there is a faithful ministry. In 1831 Tiptaft built a chapel at Abingdon, where he remained as a Baptist pastor until his death. In 1835 Mr. Philpot resigned his living and his fellowship; the temporal sacrifice entailed was such that he had to sell almost all his books. Soon after this momentous step had been taken he preached in a chapel at Newbury, which some of his friends had procured for the purpose. He writes: "When I therefore began to open up that God had a chosen and peculiar people the whole place seemed in commotion. One man called aloud, 'This doctrine won't do for me!' and started out, and was instantly followed by five or six others. I was not, however, daunted by this, but went on to state the truth with such measure of boldness and faithfulness as was given me. Some of my friends at the chapel thought that the people would have molested me, but no one offered to injure me by word or action, and I came safe out from among them." He also writes: “——is, I fear, something like the robin spoken of in 'Pilgrim's Progress, who can eat sometimes grains of wheat and sometimes worms and spiders. I am quite sick of modern religion; it is such a mixture, such a medley, such a compromise. I find much, indeed, of this religion in my own heart, for it suits the flesh well; but I would not have it so, and grieve it should be so." He preached much at Allington, near Devizes, and in the Metropolis, and many other places. His ministry was attended by crowds, and was blest to saint and sinner. In 1838 he became Pastor of the Churches at Oakham and Stamford, residing in the latter town till failing health caused his removal to Croydon. At the time of his settlement at Stamford he became associated with the "Gospel Standard," and in 1849 he was appointed editor. He was a most interesting writer on the things of God. His sermons are experimental rather than doctrinal, but when he treated of doctrine it was in a comprehensive and scriptural way, as his "Meditations" amply prove. His book on "The Eternal Sonship" practically closed the controversy which gave it birth. His "Reviews" are most instructive and brilliantly written. Would that the younger members of our Churches made a study of them! "The Advance of Popery" was another work which had a wide circulation, and events today prove the accuracy of the forecasts so solemnly made therein. His "Letters" have been a means of grace to many, and it is refreshing through them to know the spiritual history of some of the excellent of the earth in their day and generation, and to have glimpses of services at Eden Street, Gower Street, and Great Alie Street Chapels, and at Came and other places, especially in Wiltshire.”

Joseph Philpot's Letters

Joseph Philpot's Sermons