17. Of the False Church’s Claims (Part 3)

Discordance of Papistic Writers: (1) Whether Peter was at Rome; (2) How Long He was Bishop there; (3) Who Followed Him

The common tenet of the papists is. that Peter sat as the chief bishop upon the Roman throne; yet the authors whom they adduce for this purpose greatly differ. For, as respects his arrival in that city, some fix it in the year 41 after Christ; others in the beginning of the reign of the Emperor Claudius; others in the second year of this same Claudius; others in the fourth year; others in the beginning of the reign of Nero; others in the fourteenth year after Paul’s conversion, etc., as it is noted in Irenaeus, Orosius, Damasus, Hornantius, Th. Aquinus, The Lives of the Saints, etc.

Concerning the length of time he was bishop, there is not less disagreement; as also in regard to how long he was absent from his bishopric sojourning in other places. Cortesius writes of eighteen years, Onuphrius of seven years; but the general opinion among them is, that he sat twenty-five years upon the chair governing their church; although some flatly oppose it. See the last mentioned three authors.

Touching the person who succeeded him in his bishopric, there is much confusion and uncertain- ty in what is said concerning this subject. Some write that Clemens succeeded Peter; as Septimus Florens Tert.; others, that Linus followed him; as Ircnaius, Euscbius, Epiphan., etc., De Praes 32 1. Contr. Jov.; others, that Linus discharged Peter’s office two years before death of the latter; as Damasus, etc.; others, that Peter ordered that Clemens should succeed after the death of Linus; In Pontific. Petr. etc., Clem, in Epist. ad Jacobum, etc.; others, that the chair of Peter was vacant while Linus and Cletus lived, Clemens, who was ordained by Peter as his successor, not being willing, as they say, to occupy the chair in their lifetime; which is testified to by Bellarminus; others that Linus occupied the chair eleven years after Peter’s death; see Eusebius; others, that Linus died before Peter, and consequently was not his successor in the bishopric; see Turrianus, Soph- ronius, etc.; others, that Anacletus succeeded Peter, and Clemens, Anacletus. See Homil. de Agon. Pet. and Paid. In Chron, in Anno Clem.; others, finally, that Peter and Linus were bishops simultaneously in the city of Rome; yet so, that Peter was the superior, and Linus, the inferior bishop. See Ruffinus, Sabellicus, Turrianus, In vita Petri.

Of the Rise of the Popes after the Year 606, as Also of the Interruption of the Succession of the Same

Besides, that in the first three centuries after the death of the apostles, nothing was known in the Roman church, as regards rulers of the same, but common bishops or overseers, until the time of Constantine the Great, and from that time on to the year 600, only archbishops and patriarchs, but no popes, till after the year 606, when, by the power of the Emperor Phocas, the Roman Bishop Boniface I I I was declared and established the general head and supreme ruler of the whole church;—the succession also of the following popes was interrupted by many important occurrences, with respect to the manner of the papal election as well as to the doctrine and the life of the popes themselves, as also with regard to various circumstances pertaining to these matters. Of this an account shall presently be given.

NOTE.—Besides what we have mentioned in our account of holy baptism, for the year 606, of the rise and establishment of the Roman pope, there is also found, concerning the cause of the same (in the Chronijk van den Ondergang dcr Tyranncn, edition of 1617, book VII, page 211, col. 2), this annotation:

When the patriarch at Constantinople reproved the Emperor Phocas for the shameful murder he had committed, or would not consent to, or remit, it, while the bishop of Rome winked at, or excused this wicked deed, the Emperor Phocas, in his displeasure, deprived the church of Constantinople of the title, Head of Christendom, and, at the request of Boniface III, conferred it upon the Roman church; which was done amidst great contentions, for the eastern churches could not well consent to it, that the see of Rome should be considered by everybody, and everywhere, as the head and the supreme (of the) church. Compare this with Platinae Reg. Pap. jol. 123; Fasc. Temp, jol. 122; Pol. VirgU, lib. 4. cap. 10; Hist. Georg. lib. 4; Conrad. Oclntar. jol. 15; Tract, called, Ouden en Nieuwen Godt. lib. 1; M. Zanchij Tract. Pap. jol. 41; Zeg. Chron. Rom. Pap. jol.132.

Of the Election of the Pope: and of Such as Have Usurped the Chair

In the introduction to the Martyr’s Mirror (edition of 1631, fol. 25, 26, 27) mention is made from Cardinal Baronius (we have looked into his history, and found it to be so at the place referred to), of various popes who ran of themselves, with- out lawful election or mission; and also of some who usurped the chair, without the consent of the church, merely by the power of princes and potentates.

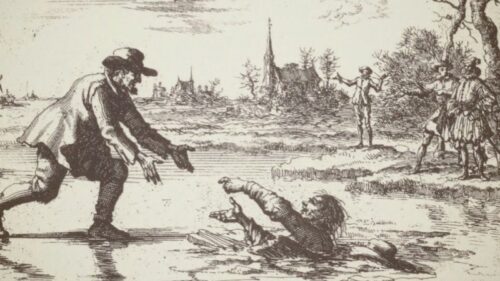

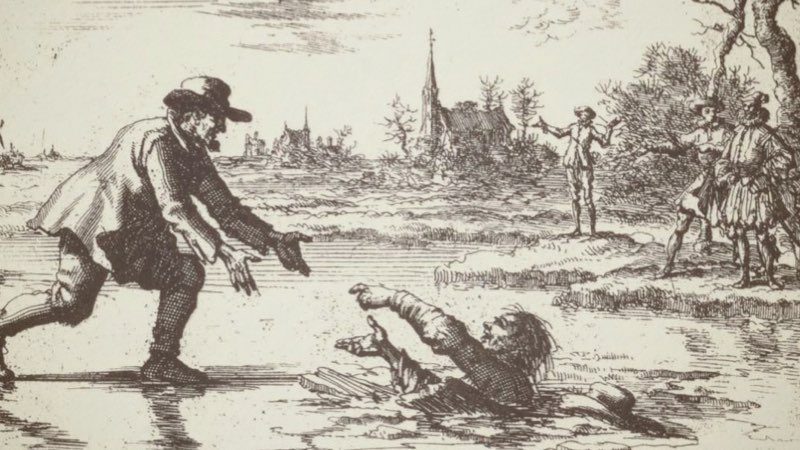

Among the popes who, without lawful election or mission, ran of themselves, are numbered Stephen VI, Christopher, and Sergius III, with whom it was as follows: Stephen VI expelled Boniface VI by force from the Roman see, after the death of Formosus; and afterwards committed an abominable deed on the dead body of said Formosus, who was counted a lawful and good pope; which deed the Cardinal C. Baronius describes from Luytprandus and others as follows:

“In this same year was perpetrated the great wickedness which Luytprandus and others relate, but incorrectly by Sergius; since the acts of the aforementioned Synod under Pope John IX, to which doubtless more credence is to be given, impute it to the then existing pope, Stephen IX.

He caused the dead body of Formosus to be exhumed, and placed it on the pope’s throne, dressed in all his papal robes; whereupon he upbraided Formosus, as though he were alive, that he through great ambition, had come from the chair of Porto into that of Rome; anathematized him on this account, had the dead body stripped of all the robes, as also the three fingers with which Formosus according to custom used to ordain, cut off from the same, and thus thrown into the Tiber. Besides this he deposed all those who had been ordained by Formosus, and reordained them; all of which he did from pure madness.” See C. Baron, histor. Eccl. Anno 897. num. 1. 2.

After this the same Baronius relates of Christophorus, who also thrust himself into the papal chair, the following:

“Further, in the following year of Christ . . . in the tenth indiction, [A cycle of fifteen years, instituted by Constantine the Great, in connection with the payment of tribute, and afterwards made a substitute for Olympiads in reckoning time. It was much used in the ecclesiastical chronology of the middle ages, and is reckoned from the year 313 as its oriirir:.—Webster’s Dictionary.] Pope Benedict IV died, and was buried in St. Peter’s church. In his place succeeded Leo, the fifth of this name, a native of Ardea, who held the chair only forty days, being expelled and imprisoned after that by Christophorus, who himself occupied the chair after him.” Baron Ann. 906. 907. num. 2.

The aforementioned Christophorus, who had expelled his predecessor, Leo V, from the chair, and taken possession of it himself, was, in his turn, robbed of the occupancy of the chair by another, called Sergius III, who was ambitious of the same dominion; which Sergius, although he attained to the papal dignity, without being elected or called, yea, more than that, was, according to the testimony of the papists themselves, fearfully tyrannical and unchaste, is nevertheless recorded with the aforementioned upon the Register of the legitimate popes of Rome. See Baron. Ann. 907. num. 2., Ann. 908. num. 3. In the midst of this account this papistic writer declares, that these were the dreadful times when every self-constituted pope immediately nullified that which his predecessor had made. Ann. 908. num. 2. Confirmatory of this matter is also that which is adduced in the “Chronijk van den Ondergang,” edition 1617, for the year 891, page 315. col. 1, 2. from the tract of “Den Onpartijdigen Rechter.”

If one will but consider, says this writer, the spiritual or ecclesiastical perfidiousness and rebelliousness of the popes, he will find in ancient history, that the Roman popes have at all times quarreled and contended with one another for the papal chair.

Thus John XXIV, having come to Bononia with many soldiers, threatened all the cardinals severely, if they would elect a pope who would not please him. When many had been nominated to him, and he would assent to none of them, he was finally requested to state whom he would elect thereto. He replied: “Give me Peter’s robe, and I shall deliver it to the future pope.” But, when that was done, he put the robe upon his own shoulders, saying: “I am the pope.” And though this greatly displeased the other cardinals, they were nevertheless compelled to acquiesce in it.

In the same manner John XXII elected himself pope when the election was committed to him. See 9th book of the above mentioned chronicle, for the year’891, at the place there referred to.

NOTE.—In addition to what has been stated in the body [of this work] concerning the popes who exalted themselves to the papal reign, it is also proper to give what may be read in the “Chronijk van den Ondcrgang der Tyrannen,” for the year 537, where the popedom of Vigilius is thus spoken of: “This Pope Vigilius was certainly impelled by the spirit of ambition; he greatly aspired to the popedom, and wrongfully ascended the papal chair, for he counseled the empress, how to expel Pope Silvcrius. He engaged false witnesses, who said that Silverius intended to betray the city of Rome secretly, and surrender it to the Goths (of which we shall afterwards speak more fully); therefore he was deposed from the popedom by force, and relegated into misery; and thus Vigilius six days afterwards became pope. The Empress Theodora desired him to reinstate Anthenius at Constantinople, as he had promised to do; but Vigilius refused, saying that one was not bound to keep a bad promise against one’s conscience.” Compared with the account of Platina, in his “Panselijk Register,” fol. no. Also, Chron. Fasci. Temp. fol. 117.

Of Some Who Attained Possession of the Roman Chair through Secular Power and Other Ungodly Means

There is, moreover, mention made of another kind of popes, who attained possession of the Roman chair, not properly through themselves, inasmuch as they were too weak, but through the power of princes and potentates, yea, even through the Arians. Among these are particularly numbered the two popes named-Felix, both of whom were exalted to papal dignity, and put in their office by Arian Kings, who ruled Italy, and consequently, also the city of Rome; the one by Constantius, the other by Theodoric, both of whom belonged to the Arian sect. Cess. Bar. Ann. 526. num. 2.

But quite the contrary happened when Pope Silverius was reputed to favor the Goths, who sided with the Arians. Prince Belizarius deposed him, and sent him away into Greece, putting Vigilius in his stead as pope. According to the testimony of Procopius. Ann. 538. num. 2.

After Vigilius, Pelagius was declared pope by two bishops only, and one from Ostien, through the favor and assistance of the emperor Justinian; notwithstanding, as Anastasius says, the bad suspicion of having caused the death of the previous Pope Vigilius, rested on him; for which reason none of the other ecclesiastics, nay, not even the laity, would have communion or anything to do with him. Ann. 555. num. 2.

Of the Dreadful Time, Called by the Papists the Iron and Leaden Century, which was with Respect to the Election of the Popes

The oftmentioned cardinal Caesar Baronius, proceeding in his account of the Register of the Popes, arrives at the year 901, the beginning of the tenth century, where he bursts out, as if with sorrow, calling this time hard, unfruitful, and productive of much evil; and comparing it to an iron and leaden century, full of wickedness and darkness, particularly in respect to the great irregularity practiced in the installing and deposing of the Roman popes; which was done partly by the Roman princes, partly by the princes of Tuscany, who, now this one, then that one, usurped the authority to elect the popes, and to dethrone them; which happened in such a manner that all the preceding abuses committed with reference to the Roman chair were mere child’s play in comparison with it.

For now, as Baronius writes, many monsters were thrust into this chair as popes; which continued throughout this whole century, yea, for a hundred and fifty years, namely from the year 900 to about the year 1049, when the German Ottoes, who occupied the imperial throne, interposed between both, although they, not less than their pred- ecessors, retained as their prerogative the right of electing and rejecting the popes. Baron. Ann. QOI. num. 1.

The same cardinal relates, that in these awful and terrible times some popes attained to the popedom not only by the power of princes and potentates, but through the foolish love of certain dis- honorable and loose women, by whom Rome was ruled; which we could in no wise believe, had not so eminent a man and rigid papist, as Baronius was, described it so plainly and circumstantially. See in Baronius’ Church History, printed at Antwerp 1623 for the year 012. num. 1; also 028. num. 1; also 031. num. 1.

Our soul is amazed, and we are ashamed to relate all that is adduced there from various papistic writers, concerning the election of some of the popes. O God! open the eyes of these blind lovers of papacy, that they may see, what succession it is, of which they have so long boasted in vain; so that they may truly turn to Thee and Thy church, and be saved!

NOTE.—With respect to this matter, the writer of the Introduction to the Martyr’s Mirror, of the year 1831, says: “After that arose a time far more horrible, etc., for the margraves of Tuscany, and after them the emperors, exercised so much violence with reference to the papal chair, that they thrust into it many monsters; among whom was John X, who was thrust into the chair by Theodora, mistress of Rome, while Lando was deposed.” Introduction, fol. 26. col. 2. from Baron. Church History, Anno 912. num. I.

After that he relates, that John X was deposed by Theodora’s daughter, who also reigned over Rome, and that John XI, a bastard child of Pope Sergius III, was put into it. “And thus,” he writes, “have whores and rogues, according to the testimony of cardinal Baronius, ruled the papal chair, deposing and instituting whomsoever they would.” Pol. 2J. col. 1. from Baronius, Anno 931. num. j. Continuing, the aforementioned author remarks: “In this iron century it also happened, that Stephen IX, having illegitimately attained to the chair, was marked in the face by some rogues, for which reason he staid in his house.” Same place, from Baronius Anno 940. num. 1.

But, in order to give an account of those particular ones only, who attained unlawfully to the papal chair, since we are treating of the succession and mission of the popes, we must also mention Pope John XII, who, being only eighteen years old, was forcibly put into the chair, and made pope by his father, the margrave of Tuscany. Afterwards he was deposed by a council at Rome, on account of his wicked life; but he remained pope nevertheless, since nobody would excommunicate the pope, however wicked his life might be, as Baronius relates. Compare Baron. Anno 955. num. 1. with Anno 963. num. 1. 2.

After that, Albericus, the count of Tusculum, made his son, who was but ten years old, pope, and by his authority put him into the chair under the name of Benedict IX. After he had reigned about nine years, a certain faction of the Romans elected another pope. When Gratianus, a priest at Rome, saw this, he bought out both of them with money, and called himself Gregory VI.

But the Emperor, not willing to tolerate this, deposed all three of them, and put Clemens II in their stead; and then Damascus II; after him Leo IX; and finally, Victor II. Thus the imperial line of the popes continued, until the clergy itself became powerful enough to elect the popes without waiting for the imperial mission, which formerly had been deemed necessary ; this afterwards gave rise to great schisms and divisions in the Roman Church. Compare concerning all this Baron. Hist. Eccl. Anno 1033, nam. 2. with Anno 1044. num. 2. 3; also, Anno I046. num. 1; Anno I048. num. 1; Anno I049 num. 2; Anno 1055.

With regard to the aforesaid matters, the writer “of the Introduction mentioned says (Fol. 2j. col. 2): “This being taken into consideration, we say, that it is not true that they, namely the Romanists, have an uninterrupted succession from the clays of the apostles to the present time, as they would make the people believe, with their long register of popes, whom they have connected as the link’s of a chain, as though they, through lawful mission had always maintained a continuous succession; but we have proved here that this chain of succession is, in many ways, broken.

“In the first place, by Stephen VII and his successors, who have forcibly thrust themselves into the chair. These certainly had no mission; and where the mission ceases, the succession ceases also.

“In the second place, by those who were thrust into the chair, without the order or sanction of the church, only by kings and princes, yea, even by whores, through lewd love; or who brought the same with money, as we have shown. These also were certainly not sent; or, if they were sent, it must be proved, by whom: for two contrary things cannot consist together. If they were sent, they did not thrust themselves into the chair, as Baronius says notwithstanding; but if they thrust themselves into it, or were thrust into it by others through unlawful means, then they were not sent, and consequently, had no succession from the apostles.” Introduction, jol. 28. col. 1.

Two, Three and Four Popes Reigning at the Same Time; the Chair of Rome Occasionally without a Pope for a Long Time

Formerly, when the papal dominion was coveted, the aim was directed solely to the Roman chair, but now it was quite different; for, instead of according to Rome, the honor of electing the pope, as had always been the case heretofore, they of Avignon, in France began, without regarding the Romans or Italians, to constitute themselves the electors of the pope; insomuch that they for this end elected a certain person, whom they call Benedict XIII, notwithstanding the Roman chair was occupied by a pope called Gregory XII; thus setting not only pope against pope, but France against Italy, and A vignon against Rome. [After pope Anastasius, Symmachus was elected pope in a tumult; and immediately also Laurentius was elected, with whom he had two contests, yet came off victor, as the papists say, for the clergy and king Diederik were on his side. But after four years. some of the clergy, who lusted after uproar and contention, and some Roman senators, recalled Laurentius; but they were sent into banishment. This caused a fearful riot at Rome.—P. J. Twisk, 5th Book, Anno 499. page 171. col. 2 ex Platinal Chron. fol. 101. Fasc. Temp. fol. 114,]

Of this, P. J. Twisk gives the following account: “At this time there reigned two popes, who were for a long time at great variance with each other; the one at Rome in Italy, the other at Avignon.” When Pope Innocentius at Rome was dead, Benedict X I I I still occupied the papal chair in France. Then Gregory XII was elected pope.” Chron. P. J. Twisk, 15th Book, for the year 1406. PaQe 75$- col. 1. ex Chron. Platinae, fol. 396. Fasc. Temp. fol. 18/.

The same writer, after narrating successively several other things which happened in the five subsequent years, again makes mention, for the year 1411, of this Pope Benedict, who was elected at Avignon; as well as of two others, who arose during his reign, namely, Gregory and John; and also of their mutual contentions. These are his words: “At that time there were three popes at once, who incessantly excommunicated one another, and of whom the one gained this potentate for his adherent, the other another. Their names were: Benedict, Gregory, and John. “These strove and contended with each other, not for the honor of the Son of God, nor in behalf of the reformation and correction of the adulterated doctrines or the manifold abuses of the (Roman) church, but solely for the supremacy; to obtain which, no one hesitated to perpetrate the most shameful deeds. “In brief, the emperor exerted himself with great diligence, and traveled three years through Europe, to exterminate this shameful and pernicious strife and discord which prevailed in Christendom. Having, therefore, rejected these three schismatic popes, he brought it about, that Otto Columnius was made pope by common consent; for, within the last twenty-nine years there had always been at least two popes; one at Rome, and the other at Avignon. When one blessed, the other cursed. See aforementioned Chronicle, 15th Book, for the year 1411. page 765. col. 1, 2.

Concerning the overthrow of these three popes the same author gives this statement: “In this year, Pope John XXIV, having been convicted in fifty-four articles, of heresies, crimes, and base villainies, was deposed from papal dignity, by the council of Constance, and given in custody to the palsgrave. When these articles were successively read to him, he sighed deeply and replied, that he had done something still worse, namely, that he had come down from the mountain of Italy, and committed himself under the jurisdiction of a council, in a country where he possessed neither authority nor power.

After he had been in confinement at Munich three years, to the astonishment of everyone, he was released, and made cardinal and bishop of Tusculum, by Pope Martin V, whose feet he submissively came to kiss at Florence. Shortly after- wards in the year 1419, he died there, and was buried with great pomp and solemnity in the church of St. John the Baptist.

After he had thus received his sentence, the other two popes were summoned; of whom Gregory XII, who resided at Rimini, sent Charles Maletesta thither, with instructions to abdicate voluntarily in his name the papal dignity; in reward of which he was made a legate in Marca d’Ancona, where he subsequently died of a broken heart, at Racanay, a seaport on the Adriatic Sea.

Benedict XIII, the pope at A vignon, remained obstinate in his purpose, so that neither entreaties nor threats, nor the authority of the council could move him, to submit, or lay down his office, for the tranquillity of all Christendom. See the aforementioned Chronicle, 15th Book, for the year 1415 page 773. col. 2. and 77./. col. 1.

NOTE.—Pope Benedict XIII, through the incitation of the King of France, and the University of Paris, sent his legates to Pope Boniface IX; but they received as an answer, that their master could not properly be called a pope, but an antipope; whereupon they refuted him. See Dc Ondergang, 15th Book, Anno 1404. page 757. col. 1.

Here it is proper to note what the last mentioned author narrates concerning the plurality of the popes, who existed at one and the same time. “Besides this,” he writes, “it is related that there were sometimes four, sometimes three, and some-times two popes at the same time.”

Victor, Alexander III, Calixtus III, and Paschalis, possessed together the papal authority, at the time of the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa; and also Benedict VIII, Sylvester II, and Gregory V were popes together, till finally, Henry III deposed them. Likewise Gregory XII, Benedict XIII, and Alexander V arrogated, by excommunications, the papal authority. Further, how Stephen III and Constantine, Sergius III and Christophorus, Urbanus V and Clemens VII, Eugene IV and Clemens VIII, and many other popes, whom to mention it would take too long, strove and contended with each other for the triple crown, their own historians have sufficiently elucidated. See in the 9th Book of the Chronicle for the year 8gr. page 313. col. 2. From the tract, Den Onpartijdigen Rechter.

How The Roman Chair

As great as was at times the inordinate desire manifested by some for the possession of the chair of papal dominion, so great was at other times the negligence and aversion as regards the promotion of the same cause; [Where no true foundation is, there is no stability; this is apparent here: for as immoderate as they were in seeking to possess the Roman chair, so immoderate they were also in leaving it vacant.] for it occasionally happened that the chair stood vacant for a considerable time, in consequence of the contentions and dissensions of the cardinals; so that the whole Roman church was without a head; without which, as the papists themselves assert, it cannot subsist.

In order to demonstrate this matter, we shall (so as not to intermix all sorts of writers) adduce the various notes of P. J. Twisk, who gives information in regard to this subject from Platina’s Registers of the Popes, and other celebrated papistic authors, in his Chronicle, printed Anno 1617 at Iloom; from which we shall briefly extract the following instances, and present them to the reader.

We shall, however, omit brief periods of a few days, weeks, or months, and pass on to intervals of more than a year, which, consequently, are not reckoned by months, or still lesser periods. In this we shall begin with the shortest period, and end with the longest.

On page 225, col. 1, mention is made of pope Martin I (in the Register the seventy-sixth), that he was carried away a prisoner by Constantine, emperor al Constantinople, and sent into exile, where he died; whereupon the chair stood vacant for over a vear. Ex. Hist. Georg; lib. 4. Platin, fol. 135. Zeg. fol. 224, 225.

Page 260, col. 2, the same writer relates of Paul I (the ninety-fifth in the Register), that he excommunicated Constantine V, who had thrown the images out of the church; and that Constantine, not heeding this, in his turn excommunicated the pope; whereupon the latter died, and the Roman chair was without occupant, and the church without a head, one year and one month. Ex. Platinae Reg- ist. Pap. fol. 166. hist. Georg. lib. 4. Franc. Allars. fol. 54.

After that he makes mention of Pope Honorius (in the Register the seventy-second), that he, having instituted the exaltations of the Holy Cross, the Saturday processions, which had to be held at Rome, the special prayers in the invocation of the departed saints, etc., was deposed by a certain council at Constantinople; and that, he having died, the chair at Rome was vacant for one year and seven months. See above mentioned Chronicle, page 218. col. 1, ex hist. Gcorq. lib. 4. Franc. Ala. Reg. fol. 44. Platin. Succ. Papae. fol. 130.

When Pope John X X I V was deposed on account of his wicked life and ungodly conduct, and placed in confinement somewhere, in the time of emperor Sigismund and the council of Constance, there was for the time of two years and five months no one who took charge of the papal government; hence the chair was without an occupant for that length of time, See aforementioned Chronicle, for the year 1411, p. 769. col. v. ex Fasc. Temp. fol. 187. Platin. fol. 401. Onuf. fol. 406. 417. Hist. Eccl. Casp. Hedio. part. 3. lib. 11. Chronol. Lconh. lib. 6. Joh. Stiimpff. fol. 21. Hist. Georg. lib. 9. Hist. Mart. Adr. fol. 53. to 66. Jan Crisp, fol. 356. to 175. Zeg. fol. 326.

Moreover, twice it happened, that for the space of about three years no one was pope, or general head of the Roman church; first, after the deposition of Pope Benedict XIII of Avignon; secondly, before the election of Otto Calumna, called Martin V, thus named because he was consecrated or ordained on St. Martin’s day. Concerning the first time, see P. J. Twisk, Chron. for the year 1415. page 774 col. 1; concerning the second, see in the same book, for the year 1417, or two years after- wards p. 781. col. 1. compared with Fasc. Temp, fol. 187 Platin. fol. 470. Hist. Georg. lib. 6. Mem. fol. 913. Seb. Fr. (old edition) fol. 31.

After the death of Pope Nicholas I (the 108th in the Register), information is obtained from Platina, according to the account of various other authors, relative to the condition of the Roman church at that time; namely, that she had no pope or head for eight years, seven months and nine days. Compare Plat. Reg. Pap. fol. 197. with Georg. hist. lib. 5. Joh. Munst. fol. 14. Mem. fol. 556. Francisc. Ala. fol. 60. Also, P. J. Twisk. Chron. 9th Book, edition of 1617. p. 297. col. 2.

Of the Ungodly Life and Disorderly Conduct of Some of the Popes

Many of the ancient writers, even good Romanists, are so replete with the manifold ungodly and extremely disorderly conduct of some of those who occupied the papal chair, and are placed in the Register of the true successors of Peter, that one hardly knows how to begin, much less how to end.

[Besides what is told in the body of the work concerning1 the ungodly life and disorderly conduct of some popes, it is related by other authors, that some of them were accused (even by those of the Roman church) of heresy, and apostasy from the Roman faith. From “Platina’s Register of the Popes, number 37,” is adduced the apostasy of Pope Liberius to the tenets of the Arians; which happened in this wise: The emperor, being at that time tainted with the tenets of the Arians, deposed Pope Liberius, and sent him into exile ten years. Put when Liberius, overcome by the grievousness of his misery, became infected with the faith and the confession of the Arian sect, he was victoriously reinstated by the emperor, into his papal chair at Rome. Compare Chron. Platinae (old edition) fol. 73. Fasc. Temp. fol. 102. Chron. Holl. div. 2. cap. 20. With P. J. Twisk, Chron. 4th Book, for the year 353, page 150. col. 2. Concerning the apostasy of Pope Anastasius II to the tenets of Achacius, bishop of Constantinople, and, consequently to the Nestorians, we find, from various Roman authors, this annotation: Anastasius was at first a good Christian, but was afterwards seduced by the heretic Achacius, bishop of Constantinople. This was the second pope of bad repute who adhered to the heresy of Nestorius, even as Liberius adhered to the heresy of Arius.—Plat. Regist. Pap. fol. 100. Fasc. Temp. fol. 113. Chron. Holl. div. c. 20. compared with the Chronijk van den Ondergang, edition of 1617, 5th Book, for the year 497. p. 171. col. 2.Some time after Honorius I had been exalted to the dignity of the Roman chair, it was found that he did not maintain the doctrines of the Roman church, but was opposed to them, although he seemed to ingratiate himself with her in some external things. Concerning this, the following words are given by a certain author: Honorius I added the invocation of the saints to the litanies: he built many temples, and decorated them with great magnificence; but this pope was afterwards condemned as a heretic, together with six prelates, by the sixth council of Constantinople. Compare—Hist. Georg. lib. 4. Franc. Ala. fol. 44. Platin. Regist. Pap. fol. 130. with the last mentioned Chronicle, edition of 1617, for the year 622, page 218. col. 1.

In addition to the evil testimony which is given of John X X I V , P. J. Twisk gives the following account: “This Pope John, as some say, forcibly took possession of the papal chair, and is styled by the ancient writers a true standard-bearer of all heretics and epicures. He was a man better fitted for arms and war, than for the service of God.”—Chronijk, P. J. Twisk, 15th Book, for the year 1411. p. 768. col. 2.]

We shall therefore, so as not to cause any doubts as regards our impartiality, not adduce all, but only a few, and these not the worst, but, when contrasted with those whom we shall not mention, the very best examples of the kind; and shall then soon leave them, as we have no desire to stir up this sink of rottenness, and pollute our souls with its stench.

Concerning the simony or sacrilege of some popes, a brief account is given from Platina and other papistic writers, in the Chronijk van den Ondergang, 9th Book, for the year 828. p. 281. col. 2. and p. 282. col. 1. The writer of said chronicle, having related the complaint of the king of France about the revenue of twenty-eight tonnen gold, annually drawn by the popes from said kingdom, proceeds, to say: “How true the foregoing is, appears sufficiently from the fact that John X X I I at his death left two hundred and fifty tonnen gold ($7,000,000) in his private treasury; as Franciscus Pctrarcha, a credible writer, plainly states.

Boniface VII, finding that he could no longer remain in safety at Rome, surreptitiously took the precious jewels and treasures from St. Peter’s coffers, and fled with them to Constantinople. Clemens VIII, and other popes, were at various times convicted of such sacrilege, by their own people. Gregory IX sold his absolution to the emperor for a hundred thousand ounces of gold. Benedict IX, being stricken with fear, sold to Gregory VI the papal chair, for fifteen hundred pounds of silver. The simony and sacrilege of Alexander VI is also sufficiently known, from his epitaph, which we, for certain reasons, omit. Further, how Leo X, through Tetzel, and many other popes, through their legates and nuncios, of the Turks (or at least, called upon them), against the French.

Their Poisoning.—Ancient writers mention, that Pope Paul III poisoned his own mother and niece, that the inheritance of the Farnesi might fall to him. Innocentius IV , through a priest, administered poison to the emperor, in a host, thus removing him from this life. Moreover, how another pope, whose name is sufficiently known, put to death by poison, in accordance with Turkish custom, the brother of Gcmeno Vajazet, the Mohammedan emperor, which was contrary to common justice, because he was ransomed with two tonnen treasure, needs not to be recounted, as the fame of it has gone out both into the east and the west.

This same pope had at a certain time determined to poison in like manner some cardinals, when the cupbearer made a mistake in the tankard contain- ing the poison (as the ancient writers have annotated), and he who had arranged this, was himself served with it, insomuch that he died with the cardinals who had drank of it. Compare Dc Tractatcn Coniarcene, Vergcrij des Onpartijdigen Rcchters, especially pp. 48, 49, 50, with the Chron sold their letters of indulgence, is better known throughout all so-called Christendom than the popes of Rome desire. Compare this with Chron. Plat, (old edition) fol. 183. Fran. Ala. fol. 58 Onpartijdigen Redder, fol. 28.

Concerning the open tyranny, secret treachery, and deadly poisoning, imputed to some of the popes, the following account is given from Vergerius and others:

Their Tyranny.—Julius II had more than two hundred thousand Christians put to death, in the space of seven years. Gregory IX caused the emperor’s envoys by whom he was informed, that Jerusalem was retaken, to be strangled, contrary to all justice. Clemens IV openly beheaded Conrad, the son of the king of Sicily, without valid reasons, or legal proceedings. It is not necessary to give a recital here, of the innumerable multitude of true Christians, who, through the pretensions of some popes, were deprived of life, in all parts of the earth, by fearful deaths at the hands of the executioner, only on account of their religion; for this is sufficiently known, and needs no further demonstration.

Their Treachery.—The Emperor Frederick, at the diet of Nuremburg, openly complained of the treachery of Pope Alexander III, and that in the presence of the princes of the empire, before whom he read the letter containing the treason, which the pope had sent to the soldiers of the Turkish emperor. Gregory II secretly issued a prohibition, not to pay to the Emperor Leo his customary (and due) tax. Alexander VI availed himself of the assistance of the Turks (or at least, called upon them), against the French.

Their Poisoning.—Ancient writers mention, that Pope Paul III poisoned his own mother and niece, that the inheritance of the Farnesi might fall to him. Innocentius IV , through a priest, administered poison to the emperor, in a host, thus removing him from this life. Moreover, how another pope, whose name is sufficiently known, put to death by poison, in accordance with Turkish custom, the brother of Gcmeno Vajazet, the Mohammedan emperor, which was contrary to common justice, because he was ransomed with two tonnen treasure, needs not to be recounted, as the fame of it has gone out both into the east and the west. This same pope had at a certain time determined to poison in like manner some cardinals, when the cupbearer made a mistake in the tankard contain- ing the poison (as the ancient writers have annotated), and he who had arranged this, was himself served with it, insomuch that he died with the cardinals who had drank of it. Compare De Traclaten Contrarane, Vergerij des Onpartijdigen Rechters, especially pp. 48,49, 50, with the Chronijk van den Ondergang, first part, for the year 1227. p. 544. col. 1. 2. Also p. 768. col. 2, of’the bad conduct of Pope John XXIV, taken from Fasc. Temp. fol. 187. Platin. fol. 401 Onufr. fol. 406. 417. Hist. Eccl. Casp. Medio, part 3. lib. 11. Chronolog. Lconh. lib. 6. Henr. Bull, of the councils, 2d Booh, chap. 8. Joh. Stumph. fol. 21. Hist. Georg. lib. 6. Scb. Fra. (old edition) fol. 31 fol. 89. Hist. Andriani fol. 53 to fol. 66. Jan Crisp, fol. 256 to 369. Chron. Car. lib. 5. Zcg. fol. 326.

Of the Divine Judgments and Punishments Visited Upon Some of the Popes

The divine vengeance for great misdeeds is sometimes carried out in this life, and sometimes reserved for the life to come. [But, after thy hardness and impenitent heart, treasurest up unto thyself wrath against the day of wrath and revelation of the righteous judgment of God; who will render to every man according to his deeds. Ram. 2:5, 6.] The vengeance which is inflicted in this life, is sometimes executed immediately by God Himself; at other times He uses means—either the elements, or things composed of the elements, yet without life; and sometimes He does it by means of living creatures as, men, beasts, etc. However, here we shall only speak of the judgment of God visited upon some of the popes in such a manner and through such means, as will be shown.

In the eighth book of the Chronijk van den Undergang der Tyrannen, for the year 767, page 262, col. 2, several examples of this kind are successively related, which we shall present here as is most suitable, and in the best possible order. [Notwithstanding, the examples, related in the body of the work are recorded by P. J. Twisk, it is proper to state, that they were extracted from various papistic writers.]

The author of said chronicle, after mentioning the ignominious expulsion of Pope Sylvester Campanus from the city of Rome, relates the sad ending of Constantine, Hadrian, John Benedict, Boniface, Lucius. Innocentius, Nicholas, Paul, Leo, Clement, etc. Pope Constantine II, having led an ungodly life, was deprived, in a council, of both his eyes, and the papal power, and then put into a convent. Hadrian III, fleeing from Rome, came to Venice in the habit of a gardener, where he was ordered to work in a garden. Hadrian IV was choked to death by a fly, which flew into his mouth, or, as others say, into his drink, while he was drinking. John XI, being apprehended by the soldiers of a certain Guido, was smothered with a pillow, which they held upon his mouth. John XXII was crushed by the falling in of the vault of a pavilion, and thus departed this life. Benedict VI,f was shut up in the Castle Angelo, by Cynthius, a citizen of Rome, and there strangled by him, on account of his great villainy. Benedict IX was killed by poison, which had been put into a fig by an abbess, who was considered a devout, spiritual daughter. The body of Boniface VII, who had died a sudden death, was dragged along the street, with his feet tied to a rope, and ignominiously buried in the common grave. Lucius II, about to storm the capitol, whither the senators had fled, was so seriously pelted with stones, that he died soon afterwards. When Innocentius IV had unjustly sentenced to death Robert of Lincoln, because he had censured, with the mouth as well as with the pen, the nefarious deeds of the popes, and Robert therefore appealed to Christ, the Supreme Judge, the pope was found dead in his bed the following day. Nicholas III died very unexpectedly of apoplexy (called the stroke of God). Paul II, having supped very merrily, died soon after, likewise apoplexy. Leo X died while laughing and frolicking at his cups. Clemens VIII, having conspired with Franciscus, king of France, against the Emperor Charles V, was afterwards apprehended by the emperor’s captains, derided above measure, ultimately reinstated in the papal chair, but finally, in the year 1534, suffocated, together with several cardinals, with the smoke of torches. From Onpar. Rccht. Also, from various other accepted authors who have previously been referred to. [Many more such examples might be related here, but, since by these few our aim is sufficiently understood, we deem it unnecessary to enter more deeply into this subject, and shall, therefore, let this suffice.]

Thieleman J. Van Braght (1625-1664) was an Anabaptist who is best known for writing a history of the Christian witness throughout the centuries entitled “The Bloody Theater or Martyrs Mirror of the Defenseless Christians who baptized only upon confession of faith, and who suffered and died for the testimony of Jesus, their Saviour, from the time of Christ to the year A.D. 1660” (1660).

Thieleman J. Van Braght, Martyrs Mirror