The Child of Liberty in Legal Bondage: Legal Strivings (10/11)

10. His legal strivings against sin and corruption while under this spirit of bondage.

He finds his soul bitter, and his temper peevish. He murmurs and inwardly frets, at everything that makes against him; and indeed nothing seems to go well with him; his spirit is stiff and stubborn; God, in a way of providence as well as grace, seems “to walk contrary to him, and he walks contrary to God. He is froward; and God shews himself froward.” His enmity against God is stirred up; and hard thoughts of God possess him, which at times are unadvisedly spoken with his lips; or, as the prophet says, “his tongue muttereth perverseness.” Against these corruptions he strives hard; but they stir not a whit the less for that. He goes forth in the morning, determined to watch his conduct more narrowly, and to be more upon his guard than ever: but, when he balances his books at night, he is just where he was, or rather worse. He then resolves, he promises, and he vows; but all in vain: he breaks through all in thought, word, and deed; for there is no spiritual might communicated to strengthen the inward man by the law, no help but from the sanctuary; no strength but out of Zion.

He now determines (like Job) to give all up, come on him what will; or else to harden himself in sorrow; when another cloud of sensible displeasure rolls over him; fears, terror, and expectations of worse to come, move him again; to work he goes afresh, and soon finds himself “plunged into the same ditch again, till his own clothes abhor him.” He stands amazed at what is come upon him; he cannot make a judgment of himself, nor of his state; nor does he know what to say. “If I say I am perfect, it shall prove me perverse; and if I am righteous I will not know my soul.” He weeps, melts, and confesses; his eye pours out tears unto God. Another billow rolls over him, and as he is again hardened, feeling himself as stubborn as an ass, and as rebellious as Satan. “Let me alone (says he), that I may take comfort a little; let me alone, that I may swallow down my spittle. Thou fillest me with bitterness, and givest me with bitterness, and givest me the water of gall to drink.” He wishes to examine his former profession carefully by the word of God; but he is too dark to make a proper judgment, and too confused to come to any point of certainty. Have I any claim upon God, or have I not? Is my faith genuine, or is it presumption? If the latter, I have committed the unpardonable sin. His heart and flesh fail at the thought, and the spirit of heaviness sinks him. A ray of light shines into him, which is eclipsed in a moment. A promise comes, but brings no power nor deliverance. Hope moves, and the soul melts; “but that passes away as a cloud.” One single word at the latter end of a sermon, and that is all; and sometimes even that is coyly put away, and in thought applied to another, who is more worthy. He cannot please conscience, nor will conscience be reconciled to him. He is in himself miserable, and he makes all miserable about him. Cheerfulness “is singing songs to a heavy heart;” he therefore hates it. He is a companion for none but those in the hospital; and if he meets one more miserable than himself, he will set to work to comfort him, and hold forth that consolation to his patient which he cannot take to himself.

He will sit down and quarrel with God; but, if he hears another at it, he will reprove him for his rebellion. He cavils at the word of God; but he cannot bear that another should. In his heart he will rail at the preacher, and at his sermon too; but he will not suffer any body else to speak evil of either. He wants ease, but he is afraid of it; he wants comfort, but refuses to take it; and he wants healing, but hates them that try to heal him, lest it should be done slighty, and lest they should cry, Peace! When God had not spoken peace. He diets himself, he fasts, he eats herbs: he scruples this and that-taste not, touch not, handle not; but he is barren still. I come now to the

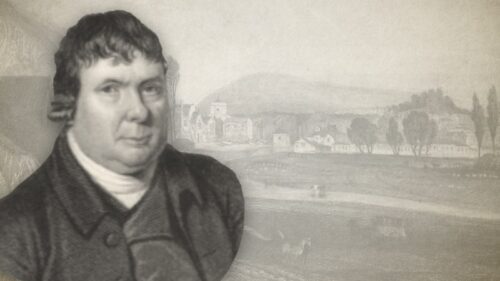

William Huntington (1745-1813) was an English Calvinist preacher and prolific writer. His influence spread across the country and denominational lines. John Hazelton wrote of him—

“He published one hundred books, large and small, and once mentions being "weary at night, after having been hard at writing for fifteen hours during the day." Henry Cole wrote of him—‘’It may be asked why in my ministration, such as it is, I make frequent allusion to the ministry of that great and blessed servant of the Most High, the late Mr. Huntington. The reasons are these—1st. Because I believe he bore and left in Britain the greatest and most glorious testimony to the power of God's salvation that ever was borne or left therein. 2nd. Because I believe he planted the noblest vine of a Congregational Church that ever was planted therein; and 3rd. Because I believe the Churches that maintain the vital truths he set forth form a very essential feature in the Church-state of Christ in the land in these times, and perhaps will do so to the time of the coming day of God's retribution."

William Huntington, The Child Of Liberty In Legal Bondage (Complete)