Chapter 4: The Eighteenth Century

“Thus saith the Lord God, Behold, I am against the shepherds; and I will require My flock at their hand, and cause them to cease from feeding the flock; neither shall the shepherds feed themselves any more; for I will deliver My flock from their mouth, that they may not be meat for them.”—Ezekiel 34:10

After the death of Oliver Cromwell nothing but God’s mercy prevented the re-establishment of Popery, and but for the faithfulness of the Nonconformists in the time of James II it would, in all human probability, have been restored. Political Protestantism prevailed, and in 1688, under William III, became firmly established. But truth languished. Ministers of the school of Burnet and Tillotson could not preach the Gospel of the grace of God; they approved it not; their doctrines respecting justification leaned more towards Rome than towards Scotland or Geneva. Amongst the papers of Laud was found a letter addressed to him by a foreign Jesuit, who exhorted him to make the encouragement of Arminianism his chief object; for that its establishment would, more than anything else, promote the growth of Popery. Arminianism was encouraged by High and Broad Church alike, and the strength of Protestantism was dependent more on its being politically valued than on its being religiously prized. Speaking generally, the eighteenth century was a dark period in the religious history of Great Britain, but in Scotland the deadly influence of the moderates was counteracted by the Erskines, Thomas Boston, and their successors. In England God raised up a very decided testimony to the Gospel. Here, and also in America, the preaching of Whitefield was followed with much blessing. It was the age of Romaine, Berridge, Toplady, Newton, Cowper, Huntington, and Gill—their writings so diverse, yet presenting a testimony harmonious with those already named in this book. It was the era of the Olney hymns and of Toplady’s poetry. His noble hymn well expresses the Gospel preached and expounded by the ministers of God’s grace in this century:—

“A debtor to mercy alone,

Of covenant mercy I sing,

Nor fear with Thy righteousness on

My person and offering to bring.

The terrors of law and of God

With me can have nothing to do;

My Saviour’s obedience and blood

Hide all my transgressions from view.”

The efforts of Lady Huntingdon, Lady Glenorchy, Sir Richard Hill, and members of his family, were not in vain. Gospel truth revived, and many were gathered into the garner of God.

George Whitefield (1714-1770) comes first as the preacher of his day.

George Whitefiled

At Pembroke College, Oxford, he was already under serious impressions when he joined the little society of students who met to study the Scriptures, to converse, and to pray. Their favourite books were “The Imitation of Christ,” and Law’s “Serious Call.” These only led him into mental confusion, till at length, after seven weeks of illness caused by soul-trouble and austerities, God removed the heavy load, and enabled him, as he describes, “to lay hold on His dear Son by a living faith,” and gave “the spirit of adoption to seal me, as I humbly hope, to the day of redemption. At first my joys were like a spring tide, which, as it were, overflowed its banks.” He was ordained deacon in Gloucester Cathedral, and then commenced that ministry in Great Britain and America which the Lord so owned and blest. His great aim was to set before his vast audiences—chiefly in the open air—their perishing state as sinners, to proclaim free grace through the blood and righteousness of Christ, and to insist upon the necessity, and unfold the nature, of the new birth, whereby they became partakers of this salvation. This was the burden of the most God-honoured evangelistic preaching England has ever known. No popular religious songs; no outward attractions; no carnal expedients; but the testimony of a man who had a deep and daily experience of sin and salvation, and who, with mighty power and eloquence, and by a voice that was most exquisitely modulated, but so clear that it could be heard at a distance of a mile, attracted alike the lowest and highest grades of society. Humble as a little child he remained until the last, and eternity alone will reveal the blessed harvest of souls given to him by his God. On one occasion, after preaching in Moorfields, he received, according to his own testimony, “at a moderate computation, a thousand notes from persons under conviction.” John Newton frequently heard him, and speaking from personal knowledge, said, in a funeral sermon preached at his death from John 5:35: “It seemed as if he never preached in vain. Nor was he an awakening preacher only. Wherever he came, if he preached but a single discourse, he usually brought a season of refreshment and revival with him to those who had already received the truth.” Cowper writes of him as Leuconomus, the Greek name for Whitefield, and says that he:—

“Stood pilloried on infamy’s high stage,

And bore the pelting scorn of half an age;

The very butt of slander, and the blot

For every dart that malice ever shot,

The man that mentioned him at once dismissed

All mercy from his lips, and sneered and hissed.”

Such has ever been the portion of those who have faithfully proclaimed the everlasting Gospel, but it matters not, for God will vindicate them in His own time.

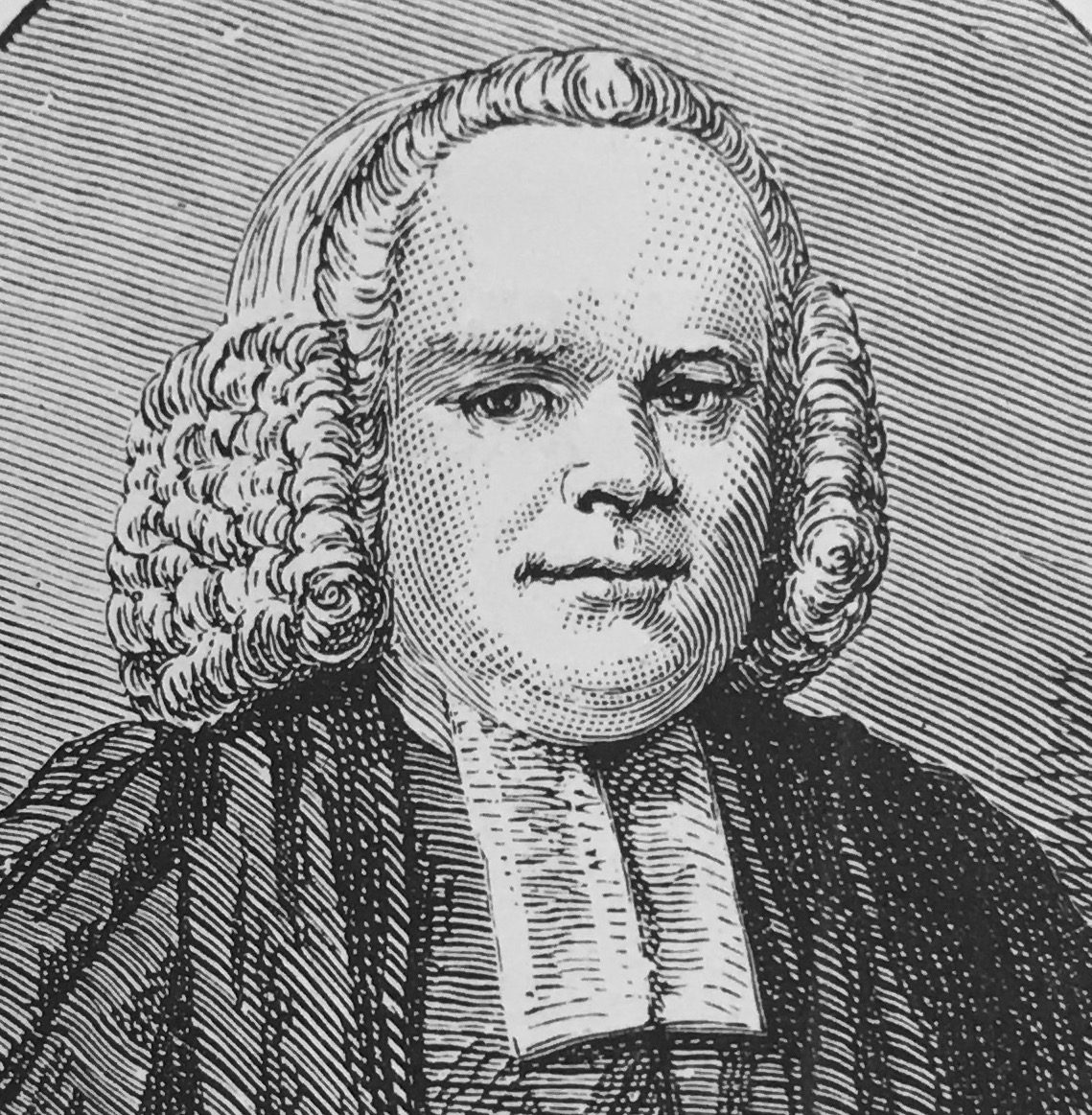

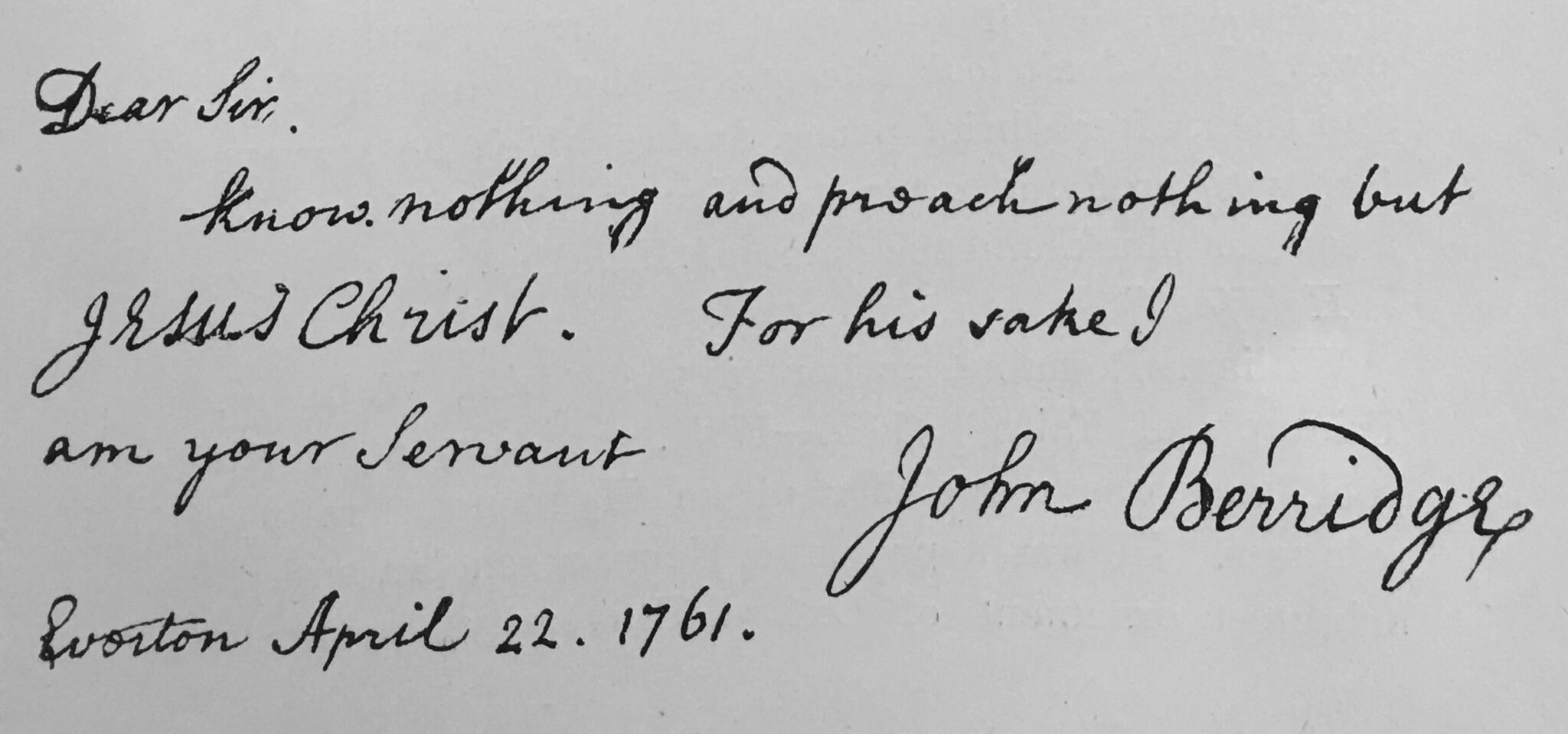

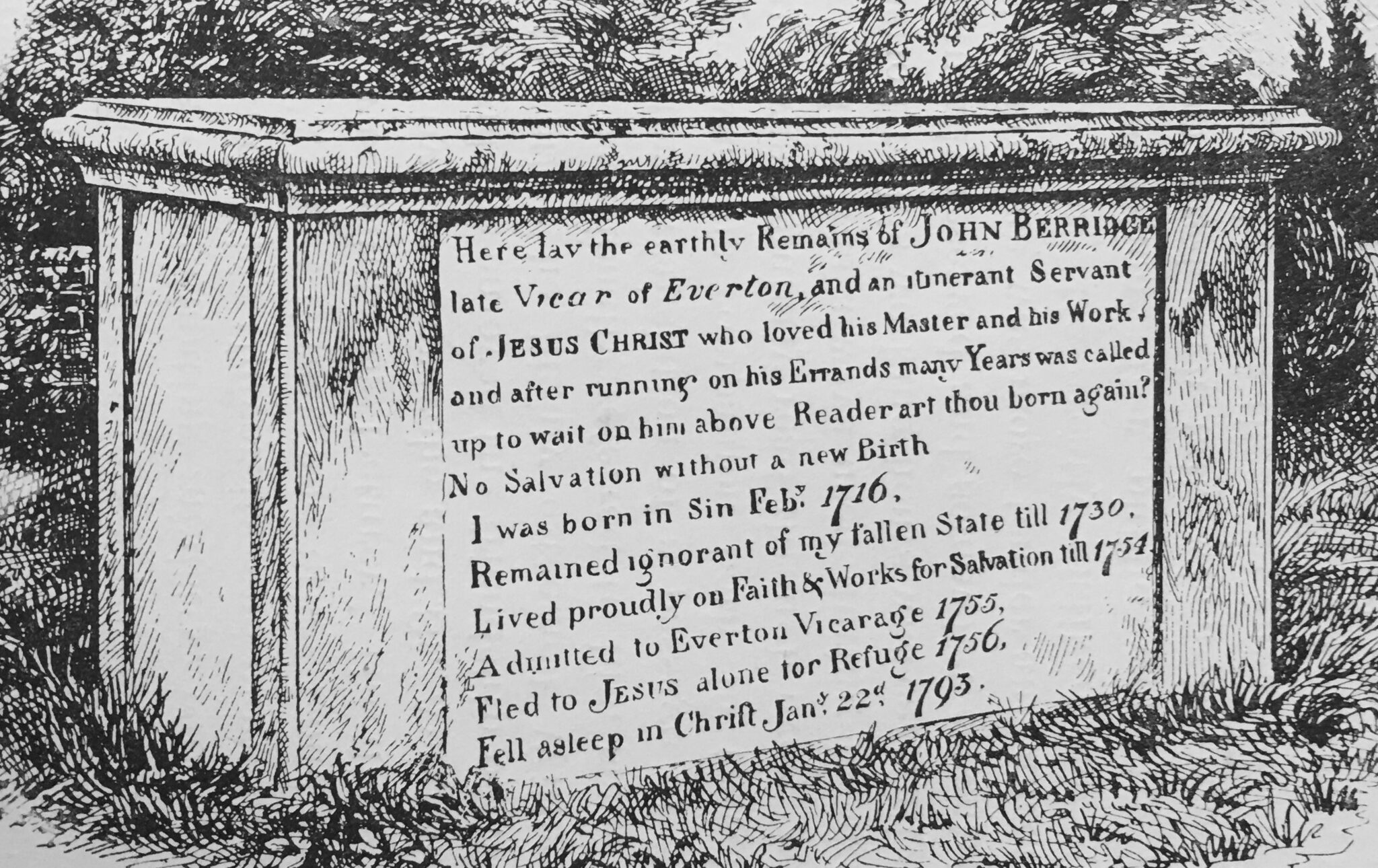

John Berridge (1716-1793) graduated at Clare Hall, Cambridge, and became Vicar of Everton, Bedfordshire, in 1755. An eminent minister of the Gospel, he was made especially useful in open-air services, ten and fifteen thousand sometimes comprising his congregation.

The counties of Bedford, Cambridge, Essex, Hertford, and Huntingdon were the chief spheres of these labours “to seek for Christ’s sheep that are dispersed abroad, and for His children who are in the midst of this naughty world, that they may be saved through Christ for ever.” Some time before Whitefield’s death he made his first visit to the Tabernacle in Tottenham Court Road. There, and at the chapel in Moorfields, he preached to crowded congregations, and was made abundantly successful in bringing many from darkness into the light of the Gospel. He perpetually aimed in his preaching at laying the creature low and exalting the Saviour. He is best remembered by his “Sion’s Songs,” a choice collection of original hymns, many of which have permanently enriched our selections. They are richly experimental and often highly poetical, and were mostly written during a long illness, during which he was delivered from Arminian error, in which, for several years, he had been entangled. His epitaph, drawn up by himself, shows what manner of man this Latimer of the eighteenth century was. He possessed a natural vein of humour and quaintness of expression. A young minister named Houseman was once introduced to him. When he entered the room Berridge rose up and kissed his forehead affectionately, exclaiming, in a quaint style of address peculiarly his own, “You don’t look like one of the devil’s children,” and then, after a brief pause, during which he surveyed him with profound interest, “Young man, you have had a famous pluck, and the name of Him that plucked you is Holdfast.”

John Berridge’s Tomb

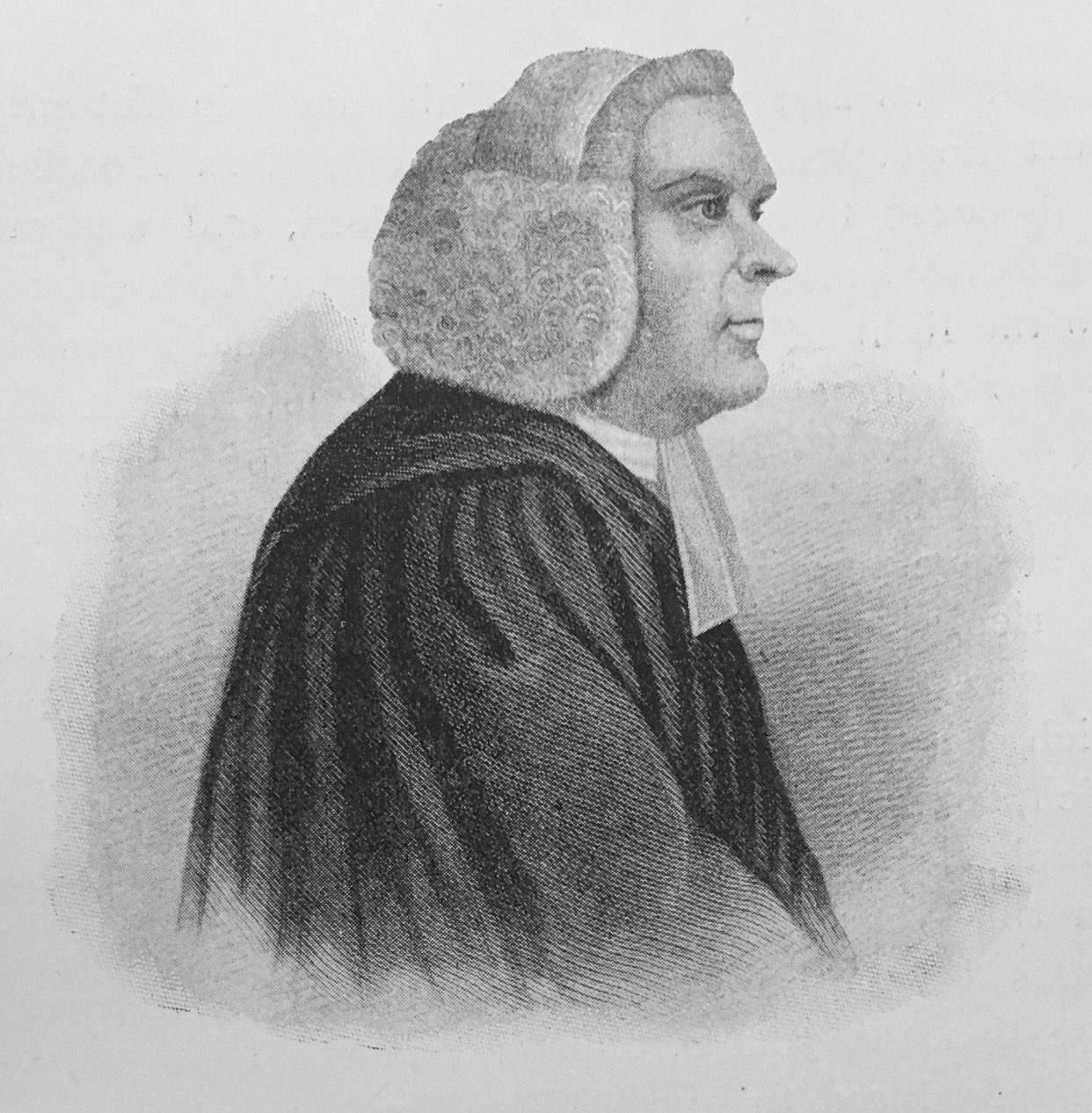

William Romaine, author of the “Life, Walk, and Triumph of Faith” (1714-1795), was born at Hartlepool, and was a member of an Huguenot family of refugees. He was a profound Hebrew scholar, and the brightest ornament of Oxford University during his career there. He was upwards of thirty years of age when the Lord was pleased to let him see and feel the plague of his own heart. He writes: “In despair of all things else, I betook myself to Jesus, and was most kindly received.” He endured much persecution because of his discriminating ministry, which was sometimes exercised at his University, and more frequently at St. Dunstan’s, Fleet Street, and other London churches where he was curate or lecturer. He died rector of St. Andrew by the Wardrobe and St. Ann, Blackfriars. On the one side he enjoyed the friendship of Whitefield, and on the other he highly esteemed William Huntington, who occasionally referred to him some question as to the literal translation of a passage of Scripture. His Bible was his companion both in travel and at home, and was regularly read through every year. His Hebrew psalter was always used during breakfast, and every period of his working hours was carefully mapped out. Naturally reserved and somewhat eccentric in his disposition, no man was more tender and affectionate to those around him. He greatly disliked the custom of general conversation after public worship, and frequently interrupted such talk when he came out by tapping the shoulders of those so engaged. For many years he lived in Walnut Tree Walk, Lambeth, where he delighted in dressing, keeping, and planting his little garden. His last words were: “He is a precious Saviour to me now,” and ” Holy, blessed Jesus, to Thee be endless praise.” His letters are of great spiritual value. His friendship with James Hervey, rector of Weston Favel, author of “Theron and Aspasio” and “Meditations,” is evinced by the funeral sermon he preached on the occasion of his death in 1759.

The writings of Augustus Montague Toplady deserve to be closely read and studied to-day. He is best known by his hymns, but his prose works are of extreme value, and are well fitted to ground young believers in the distinguishing doctrines of the Gospel. His life extended only to thirty-eight years (1740-1778), yet what a harvest has resulted from his labours! An ardent spirit, lodged in a weakly body, soon wore out his physical frame. In peace and joy he was ready to be gone, and in his own words:

“Then, when my summons bids me come up higher,

Well pleased, I shall from life retire

And join the burning hosts beheld at distance now.”

Whitefield’s ministry and friendship were attended with important spiritual benefit to him, and he ever spoke of this great preacher as one of the most eloquent and useful since the days of the apostles. Toplady was but sixteen years of age when in a barn at Codymain, in Ireland, the Lord called him by His grace under a sermon by a plain man named Morris from “Ye who sometimes were far off are made nigh by the blood of Christ.” His “Historic Proof of the Doctrinal Calvinism of the Church of England,” and his essays and sermons are of living interest. He read fast, slept little, and often wrote like a whirlwind, and though his body was weak it did not obstruct him, for he seemed to leave it behind. In the pulpit his voice was music, and spirituality and elevation seemed to emanate from his slight form. It was remarkable how much he accomplished, both at Broad Hembury and afterwards in Orange Street, Leicester Square. Within an hour of his death he said, bursting into tears of joy, “No mortal can live after the glories which God has manifested to my soul.” Referring to the controversies in which he had been involved, he writes of his opponents in words that will appropriately close this reference to him: “Let it not be supposed that I bear them the least degree of personal hatred. God forbid! I have not so learned Christ. The very men who have my opposition have my prayers also. I dare address the Great Shepherd and Bishop of Souls in those lines of the late Dr. Doddridge:

‘Hast Thou a lamb in all Thy flock

I would disdain to feed?’

But I likewise wish ever to add:

‘Hast Thou a foe before whose face I fear

Thy cause to plead?’

Grace, mercy, and peace be to all who love, and who desire to love, our Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity.”

Augustus Montague Toplady

Toplady held in high regard Dr. John Gill (1697-1771), and applied to him and to his controversial writings what was said of the first Duke of Marlborough—that he never besieged a town that he did not take, nor fought a battle that he did not win. Gill’s book on the Canticles is a beautiful and experimental exposition of Solomon’s Song; his “Cause of God and Truth” is most admirable and suggestive; and his “Body of Divinity” one of the best of its kind. His commentary upon the Old and New Testament is a wonderful monument of sanctified learning, though it has been so used as to rob many a ministry of living power. It is the fashion now to sneer at Gill, and this unworthy attitude is adopted mostly by those who have forsaken the truths he so powerfully defended, and who are destitute of a tithe of the massive scholarship of one of the noblest ministers of the Particular and Strict Baptist denomination. The late Dr. Doudney rendered inestimable service by his republication, in 1852, of Gill’s Commentary, printed at Bonmahon, Waterford, Ireland, by Irish boys. Gill was born at Kettering, and passed away at his residence at Camberwell, his last words being: “O, my Father! my Father!” For fifty-one years, to the time of his death, he was pastor of the Baptist Church, Fair Street, Horselydown, and was buried in Bunhill Fields. His Hebrew learning was equal to that of any scholar of his day, and his Rabbinical knowledge has never been equalled outside Judaism. His “Dissertation Concerning the Eternal Sonship of Christ” is most valuable, and this foundation truth is shown by him to have been a part of the faith of all Trinitarians for about 1,700 years from the birth of our Lord. In His Divine nature our blessed Lord was the co-equal and co-eternal Son of God, and as such He became the Word of God. The Scriptures nowhere intimate that Christ is the Son of God by office, or that His Sonship is founded on His human nature. This is not a strife about words, but is for our life, our peace, our hope. Dr. Gill’s pastoral labours were much blest; to the utmost fidelity he united real tenderness, and at the Lord’s Supper he was always at his best.

“He set before their eyes their dying Lord—

How soft, how sweet, how solemn every word!

How were their hearts affected, and his own!

And how his sparkling eyes with glory shone!”

The hymns of Joseph Hart (1712-1768) are a priceless possession of the Church of Christ. They were first published in 1759, and today occupy high rank in experimental religious poetry. As the Lord’s people grow in grace so their love to these hymns increases, for they so well portray the pathway marked by “the footsteps of the flock” and cast a flood of light upon the paradoxes of the Christian life; those upon the sufferings of our Lord are among the most beautiful and solemn of such compositions. His noble hymn on the Scriptures is most useful in view of the destructive errors of the day with regard to the plenary inspiration of the Bible:

“Say, Christian, wouldst thou thrive

In knowledge of thy Lord?

Against no Scripture ever strive,

But tremble at His Word.”

His experience, prefixed to many editions of his book, is a heart-moving record of God’s dealings with his soul, and full of sentences replete with sanctified wisdom. “Pharisaic zeal and Antinomian security are the two engines of Satan with which he grinds the Church in all ages as betwixt the tipper and the nether millstones. The space between them is much narrower and harder to find than most men imagine. It is a path which the vulture’s eye hath not seen, and none can show it to us but the Holy Ghost.” “The dealings of God with His people, though similar in the general, are nevertheless so various that there is no chalking out the paths of one child of God by those of another.” “That for a living soul really to trust in Christ alone when he sees nothing in himself but evil and sin, is an act as supernatural as for Peter to walk the sea. That mere doctrine, though ever so sound, will not alter the heart; consequently that to turn from one set of tenets to another is not Christian conversion.” “That a whole- hearted disciple can have but little communion with a broken-hearted Lord.” In the first part of his career he was a teacher of the Latin and Greek classics, hence the beauty and exactness of his phraseology. He need be a bold man who tries to amend a line of Joseph Hart’s. His public ministry commenced only eight years before his death and he had but one pastorate—that of the Independent Church meeting in Jewin Street, Aldersgate. It is a sign of mental and spiritual decadence that these hymns have been in many quarters superseded by unscriptural and sentimental rhymes, chiefly sung for the sake of the popular tunes to which they are set.

The monument erected over his grave in Bunhill Fields more than thirty years ago is unique as being the only modern memorial there. From about 1668 till the middle of the nineteenth century this Cemetery was used for interments. James Hervey’s “Meditations Among the Tombs in a Country Churchyard” are beautiful and suggestive, and in Bunhill Fields profitable thoughts will arise concerning those of whom it can be said:

“Their flesh here slumbers in the ground,

Till the last trumpet’s joyful sound;

Then shall they wake in glad surprise,

And in their Saviour’s image rise.”

John E. Hazelton (1924) was a Strict and Particular Baptist preacher. He was the son of John Hazelton (1822-1888). He was appointed the Pastor of Streatley Hall, London. In the December 1924 Issue, the Gospel Magazine wrote of him:

“For a period of fifteen years he faithfully ministered the Word of life to the Lord's people who met in Streatley Hall, London, and these are a selection of the sermons he preached there, lovingly collected together, and printed in book form. By way of introduction there is also printed A Declaration of Faith by Mr. Hazelton. This was found amongst his papers. It has never before been published. It is full of valuable teaching of such subjects as "The Peril and Needs of Our Churches," "The Holy Scriptures," "The Everlasting Covenant," "The Church," and "The Doctrine of Grace.” Mr. Hazelton was an able preacher of the everlasting Gospel, and he loved to exalt Christ and to abase the sinner. These sermons are full of rich Gospel teaching. They tell of a full and an eternal salvation, arranged and planned in the great Covenant of grace before the foundations of the world were laid. They tell of the electing love of God the Father, the redeeming work of God the Son on behalf of His Church and people, and of the regenerating and sanctifying work of God the Holy Ghost. They tell of the blood and righteousness of the Divine Surety of the everlasting Covenant. They are marked by fulness of Gospel truth and by tender and loving words to seeking and penitent sinners. They display a considerable knowledge and much care in preparation. They are the words of a true man of God who in dependence on the aid of the Divine Spirit earnestly proclaimed the Gospel of Divine grace in the prayerful hope that God the Holy Ghost would use the message as the means of regenerating the sinful objects of His eternal mercy. Space will not allow us to quote from these pages, but we strongly advise our readers at once to get the book and make it point of reading one of the sermons every week. Mr. Hazelton was called home on May 8th last. His last sermons were preached on April 6th and 13th, and they form the concluding sermons of this volume. A beautiful portrait of the beloved author forms the frontispiece. By these sermons, and by his valuable Declaration of Faith, he being dead, yet speaketh.”

John E. Hazelton Sermons

John E. Hazelton's "Hold-Fast" (Complete)

John E. Hazelton's Declaration Of Faith (Complete)