18. The Sentence of Death in Ourselves

Preached on Sunday Evening, May 9th, 1841, in Gower Street Chapel.

“But we had the sentence of death in ourselves, that we should not trust in ourselves, but in God which raiseth the dead.”—2 Corinthians 1:9.

In the fourth verse the apostle says, “Who comforteth us in all our tribulation, that we may be able to comfort them which are in any trouble, by the comfort wherewith we ourselves are comforted of God.” Now I have been there in some solemn measure in my conscience; and sometimes I have been there not very pleasingly, and sometimes more pleasingly. My flesh and blood, at times, have murmured to think I must go deeply into certain conflicts, certain tribulations, certain distresses, certain miseries, both within and without, to be an instrument in God’s hand of leading some hobbling soul in the same hobbling hole; and I have been ready to say to the Lord, “Lord, I think I have enough to do with my own troubles, without being plagued with other people’s;” and thus insult the Lord, instead of taking it kindly in him that he should make me the instrument of comforting his family. But at times, when the Lord has been pleased to appear in a sweet and blessed way, I really have been enabled to give God leave to put me where he will, and do what he will with me, so that it may but be the means of leading his poor, tried people in their temptations, and thus comforting “them which are in any trouble, by the comfort wherewith we ourselves are comforted of God.”

“For as the sufferings of Christ abound in us, so our consolation also aboundeth by Christ.” Now did you ever enter into the spirit of that text, that it is “through much tribulation we must enter the kingdom?” It does not appear to me that it really means only people going to heaven through tribulation; but I believe in my conscience we never get spiritually, feelingly, blessedly, and God-glorifyingly into any branch of God’s blessed kingdom, but through tribulation. The mysteries of the Gospel of God are suited to the various conflicts and trials of his people; and when God is about to reveal any special blessing, any special, manifested mercy to his children, there is always some conflict or other connected with it. I have proved it in my own experience that it has either been to prepare the mind for some trouble, support it in some trouble, deliver it out of some trouble, or in some way or other there has been trouble connected with it; and I really would not give a “Thank you” for any man’s religion, if it is not connected with trouble. And yet my fleshly heart will sometimes tell God that I want no more trouble. But then be will not believe me, nor act upon it. God, in the riches of his grace, sees to it that we shall have conflicts, internal and external; and the more we slip, the deeper those conflicts shall be. And then God sends consolations,—consolations greater than the miseries; and we are brought to feel the blessedness of the salvation of God, in the rich openings of it, as suited to our condition; and he is glorified therein. I believe an untried minister may preach his people up to a condition of presumptuous confidence; but their consciences will be as dry as these candlesticks. If there be no conflict, if there be no trial, there will be no dew there. There must be trials and perplexities; and it is in them that mercy rejoices over judgment, and the soul is brought to enter spiritually into God’s glory, and to know that the comforts and consolations of the gospel are suited to the condition of the church in their various trials; and God is glorified thereby.

“And whether we be afflicted, it is for your consolation and salvation.” What! Must the apostles be afflicted for the consolation and salvation of the church? I felt a little of this in my last affliction; and I thought, “Lord, I am suffering; but why should l murmur and grumble? Perhaps thou hast some wise end in this.” And 1 believe he had; and! was brought to see that it was the design and will and purpose of God to bring me into such places, both in body and mind, as to make a way for God to open the mysteries of his love and grace to me, that 1 might carry a little of the tidings of the goodness and love of God to poor, hobbling sinners. When I am in a right mind, there are none in the world I feel so much agreement with as poor, hobbling sinners. As for those who can help themselves, I have nothing to do -with them, and do not want to have; but when I find those who can do nothing, who are altogether dependent, upon the Lord, I feel a blessed union of soul with them.

“Which is effectual in the enduring of the same sufferings which we also suffer.” I know how you go on (at least how my people go on, and I believe you are all alike). Sometimes you are ready to think the minister gets rather dry, and then you secretly pray, perhaps, that God will bring him into trouble. You never dream that perhaps you are dry, and that God must bring you into trouble. No, no; none of that. It is the poor minister who is to have all the trouble and you must have all the profit. But God overrules you; and he brings the minister into trouble and brings you into trouble; and his trouble and your trouble and his consolation and your consolation bring you into a blessed oneness; and so you are led to glorify God’s method of opening his love and mercy and consolation to your souls.

“And our hope of you is steadfast; knowing that as ye are partakers of the sufferings, so shall ye also be of the consolation.” Why, it is so, brethren. We feel a sweetness sometimes in the matter before God, that these poor, tried, troubled, and helpless creatures will by and by come away with the sweet, unctuous enjoyment of the consolations of the Gospel of God, and that we and they shall meet together to crown the brow of God in the world to come, and to show forth his praise for ever and for ever. And therefore we have this “hope,” and a “steadfast” one too.

“For we would not, brethren, have you ignorant of our trouble, which came to us in Asia, that we were pressed out of measure, above strength, insomuch that we despaired even of life.” Now even in a bodily sense they were “pressed out of measure, above strength;” aye, and in a mental sense too, in a soul sense. There are times and seasons when the child of God, when the minister of Christ, is so “pressed out of measure” in the conflict of his mind that he has no more manifest strength to support himself than he has to hold up the world; and he is obliged to sink; and he wants strength to sink. It really appears sometimes to me that he can neither walk nor stand still, nor sit still; he seems as if hung upon nothing. And how it is that he does not sink into black despair, he sometimes stands amazed before God. And thus he is in a variety of ways “pressed out of measure.”

But eventually the matter appears, agreeably to God’s Word, to the consolation of his people. And the apostle tells us in the next verse how it is: “We had the sentence of death in ourselves, that we should not trust in ourselves, but in God which raiseth the dead.”

Now let us just endeavour,

I. To look at this sentence of death in ourselves.

II. The design God has in view in it; which is, to cure us of self trust: “That we should not trust in ourselves.”

III. Well, then, is he to leave us in black despair? No; but eventually to bring us to trust “in God which raiseth the dead.”

I. I would just notice that sometimes when God begins a work of grace in the heart of a poor sinner, and especially if that sinner is young, he brings the sentence of death upon all the poor creature’s earthly pursuits, earthly joys, and earthly prospects. There may be a young man, or a young woman, just springing up into life, so as to begin to look about them for greater prospects; and the principal concern for a while is to see how they shall manage to make their fortune in the world, how they shall manage to go on with what the world calls great respectability; and just as they are laying their plans, God sends the sentence of death into their souls and slaughters all their prospects and plans. They had imagined that they had a little foresight and a little wisdom, and perhaps looked upon some others with a degree of astonishment that they should be such fools and not manage things better; they themselves have laid their plans with a good understanding, and no doubt but they shall be prosperous. God mows them all down. God slaughters the wretch, makes him into a fool, a mere fool; and he feels before God that he has not wisdom to direct his steps for a single moment. And now he is confounded and wonders where this will end. And it is thus, when things are just springing up into pleasing appearances, whatever state he may be in, that when God quickens his dead soul he sends the sentence of death into his conscience upon all his creature enjoyments. If the man is living in carnal pleasure and prospering, as he thinks, in the pursuit of it, the sentence of death comes into it,— mars it all, spoils all. Terror, misery, despair hunt him out of ail his creature enjoyments and all his fleshly pursuits. Sometimes he thinks he will struggle against this; he will drown it in some vain amusements of the world. Perhaps he takes himself to the playhouse, to some merry company, to some amusement, with a view to drown this perplexity and confusion of mind that he feels. And God goes there too. “Why,” say you, “you do not think that God goes to the playhouse?” Aye, many a time, and to dancing-houses too, when he has a poor sinner there that he is determined to bring under the sentence of death. He goes to mar the creature’s comfort. While the man goes to drown his guilty fears, God goes to send a fresh spring, to make them rise higher. And the poor creature concludes that all his happiness and all his enjoyment are gone for ever, and that there is nothing but misery for him. In whatever station of life he is, the sentence of death is passed upon it all.

And if he has been a person brought up in what they call religion; if he has had religious instruction and his judgment is pretty well stored with religions knowledge, so that he can talk about election, predestination, redemption, final perseverance, and all the leading truths of the gospel, and is ready to think that, owing to the judgment that he has, though there must be some little change, it need not be very conspicuous, because he knows so much already and has got so far on in knowledge;—if ever God begins a work of grace in that poor sinner’s heart, he will make him into a mere fool. All his knowledge will give way; the sentence of death will come upon him; and he will find, instead of his knowledge being of any real service when God sends his quickening Spirit and gives him divine life, it only seems to puzzle him, to confuse him. And perhaps there is some poor soul here this night who wishes he had never known a word about truth till God had been pleased to quicken him; for he is ready to conclude that all he has is what he knew before, and that he has no real vitality; he wishes he had never had a particle of knowledge about it. And thus comes the sentence of death upon all his knowledge and all his understanding of religious things; as it is said,” That we should not trust in ourselves, but in God which raiseth the dead.”

But by and by, whatever our state may be when the Lord takes us in hand and quickens us by his Spirit, and brings a sentence of death upon all our worldly prospects and enjoyments, anon he gives us a little feeling after mercy, a little breathing after pardon and manifested salvation; and then most likely a legal feeling begins to induce us to rest in this feeling after mercy and this breathing after salvation, to take satisfaction there, so as not to be looking for any more. Now if you are endeavouring to walk there, as sure as there is a living God, the sentence of death will come upon that. This is a trusting in your breathings and pantings rather than any real thirsting for that which cannot die,—the life of God; and, therefore, the sentence of death shall come upon it; and you will be brought perhaps by and by to such a state that you cannot breathe after mercy, you cannot pant for mercy, you cannot feel a thirsting for God; and you wonder what is the matter now. AH seems to go wrong now. You did have a little hope some short time ago, when you could have a little breathing and feeling and panting after God; but that is gone, that is sunk; and you feel as if you had no feeling. If you have any feeling at all, it is to feel that you have no feeling, that you are a kind of dead weight, and that you sink under it, and cannot revive your soul. And thus you have the sentence of death in yourself, that you should not trust in yourself, but in God that raiseth the dead.

Now, however, the Lord, in the riches of his grace and mercy, is pleased to come with his reviving power, and put it into your heart to be vehement with God in prayer; for whatever you may think, there is such a thing as being mighty in prayer. It is not the idea of doing your duty, a duty religion, being “pious.” Merely doing your duty is a mere fleshly religion altogether. There is a solemn vitality in the mysteries of the cross of Christ; and the poor soul is brought to be vehement and agonizing with God, sometimes in a state of desperation, and is ready to cry out as in agony, “O Lord, undertake for me; for I am ruined. O Lord, if it be possible, save me; for I am undone.” And he feels what he says, and says what he feels; he is brought from real necessity to be violent in praying about his soul to God, and knows something of the kingdom of heaven suffering violence; though he cannot at present feelingly Bay that “the violent take it by force.”

Now almost beyond doubt the enemy will be ready to say, “Ah! Now, as you have been so vehement, so powerful in your prayers, you may expect a blessing. You have now, as it were, tired the Lord; he is sure to come note.” Do you not see how artful, how detestably artful the enemy is, to blunt the edge of prayer and to bring you to some creature trust, instead of looking to the Lord for all you have and all you are that is above nature? As sure as ever you get there, this vehemence will go. You will find you cannot pray mightily or vehemently. And then you become so wretched that at length you are obliged to say, “Lord, what am I? I can neither pray nor let it alone, neither believe nor disbelieve, neither hope nor do anything that is worthy of a sinner who needs help. All I can really say of myself is that I am a mass, a dead mass, of stinking pollution. That is all I am and all I have in self and of self.” Well, the sentence of death has come upon all your self-trust,-—your religions self as well as your profane self; and this is making way for God’s blessed salvation, in a way according to the mysteries of his everlasting love.

But anon the Lord is pleased, perhaps, to reveal pardon. I recollect the time when God was pleased to reveal pardon in my poor soul at first. O what sweetness and solemnity and blessedness there was in my poor heart! I sang night and day the wonders of his love; and I never dreamed but I should go singing all the way to heaven. I never expected to hang my harp upon the willows, or even to find it out of tune, lint, alas! alas! The harp was afterwards out of tune; and it wanted God to string it; I could not put it in tune. It is when the Lord the Spirit comes that he teaches the soul how to sing the wonders of his love. l could see afterwards how my poor soul had been led on. l had had a zeal for God, but it was grounded in self; and l had felt God’s free love come to my soul as a matter of free favor, but there was self at bottom thinking, “I will keep this, and cultivate it, and bring it more and more to maturity, till I grow up into such spiritual enjoyment that there will not be one in the neighborhood who shall excel me.” And I really was sincere; but then this was the sincerity of self; for if it had not been self-sincerity, it would not have put in this I—the great I—what I will be and what I will do. Whenever it comes to this, poor child of God, whenever you begin to swell with your great I, what I will do and what I will not do, depend upon it, death is at the door; there will be something that will bring the sentence of death upon all your comfortable feelings and enjoyments. I could tell you how it brought me to lose my sweet enjoyment, or rather to have it removed. I have thought very blessedly sometimes of that sentence of the Lord by the apostle John: “I have somewhat against thee, because thou has left thy first love.” He does not say lost it, but left it. No, thanks be to God, it is not lost; it is secured in our blessed Christ; but we go from it in our feelings. The fact is, I was amazingly zealous. I was a youth between 17 and 18 years of age, and very moderate in my living; and I looked upon anyone that conducted himself with any degree of immoderation (or what they called moderation) as proving that they had not vital godliness. Two old men I cut off entirely; one for going to sleep in prayer, and the other because he told me that he should not wonder if I became intoxicated that week; it was in the fair-time. “For,” said he, “you seem so lifted up with your power to keep from it; and the only thing in your favour is that you do not like it;” for I did not like liquors then. I looked at the poor old man as an old hypocrite. “What! I get intoxicated, when God has been so gracious as to stop me in my mad career, and give me pardon, and a sweet, conscious enjoyment of it!” I could not believe it; and I could not believe he had the life of God in his heart, because he could think it possible. And so I went singing on. But before the week was out, there was poor I, intoxicated! Ah! How dreadful I became in my feelings! I must tell you that I did not take anything you would think was drinking to excess; for I had only had one three-halfpenny worth of stuff. But there, all my comfort wan gone and enjoyment gone. Then I thought, one night, I would put out my light and go upon my knees by my bedside, and never cease praying all that night until God pardoned me. You see there was a little I still. So on my knees I went with a determination to pray all night. Some time in the morning I awoke, and found I had been asleep on my knees; and so there was poor I, who had cut off one poor old man for going to sleep in prayer and another for saying he should not wonder if I got intoxicated, actually getting intoxicated, and going to sleep in prayer myself into the bargain. There was the sentence of death upon all my joy and all my comfort; and for several months after that, I walked in the very depth of agony and distress, such as I could never describe; so much so that if any child of God came into my company who knew the preciousness of Christ, I believed they would see it directly we began to converse, and go and tell all the people in the village (for I knew everybody, and they knew me), and that I should go wandering about like Cain with a mark upon me; and so I kept out of their company. And then the enemy of souls would come in: “Where is your peace with God now? Where is your power in prayer now? Where is your meekness, your humility, and your tenderness of conscience now? Where is your hope in the Lord now? Where is your trust in the God of Israel now? And where are you?” “Ah! Lord,” I was obliged to say, “I do not know where I am, nor what I am, nor what the end will be.” The sentence of death was passed upon the whole. And, perhaps, here is some poor soul who really has had the sentence of death upon all he has had and all he has enjoyed, upon all he has done and all he thought he was capable of doing. “Well,” say you, “that is just my case.” Then if you have passed through this path and had your hopes of a religious nature (as far as they have been formed in flesh) all cut off, and the sentence of death has come upon you and mowed you down and rooted you up, and made you feel as dry as the bones in Ezekiel’s vision, I believe he will come in his own blessed time, and that the sentence of death is hound upon you that you may not trust in yourself, but be brought feelingly and spiritually to trust in the living God.

But even after the Lord has delivered you, self works up in a variety of ways:! Now I will be more watchful; I will be more cautious and tender; I will not be so rash. I will keep my eyes open, and my ears open, and my heart open to the truth, and I will walk more circumspectly and steadily, that I may not again bring the sentence of death upon my joys and my peace, and that I may not again get into this trouble.” Well; for a little time, perhaps, you maintain it; perhaps not a week. You begin to be incautious; you get into company, perhaps, and a light and trifling spirit comes over you, and you let out a few light and trifling words; and those words come like daggers to your heart and strike you to death. The sentence of death is upon you again. And thus you go on, from time to time; and the sentence comes upon all your hopes and expectations that spring from self in any bearings of it whatever.

But by and by you get to what you think a sweeter frame of mind than this. You have some sweet peace and heavenly joy, some blessed intercourse with the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, some divine springings up of love and of patience. Then God puts you into circumstances to try your patience; and you take it patiently too, meekly and resignedly, as it becomes you. You also give some demonstrative proof that the fear of God awes you and draws you, that you really do act more as becomes a child of God, and that there is more tenderness of conscience maintained. And now, if you are not led by the Spirit of God to beware, you will begin to trust in this tenderness of conscience and patience and meekness of yours.

Really, brethren, I hardly know how to decide the matter; for I feel it very difficult to maintain a distinction in my own conscience, betwixt being satisfied without feeling and making feeling my trust. I believe an unfeeling religion is the devil’s own religion, and is not the religion of the Son of God; and yet to put trust in the feelings rather than in the God whence they come, is insulting the Spring- head, insulting the Fountain. But we are as prone, in some of our sweet feelings, to put a little trust and confidence in our feelings as we are to breathe. And then the Lord takes these feelings away, and we have none to trust. Then the enemy tells us it has all been a delusion, all a deception, and we have no real, vital godliness; for if we had and these feelings had been real, we should have remained in them. Perhaps I am speaking in the ears of some who “know they are not going to be such crazy fools as that; they have more sense.” Let me tell you God s people’s religion is not a common-sense religion; they cannot move on by a common sense religion. They find it has the sentence of death in it, and they sink under it, because there is no ground of rest in it. And so, perhaps, they go to the Lord, and pay, “Lord, how is it? I really wish to love thee and to live in thy fear; I desire to honour thee. I want to have my mind stayed upon thy precious, manifested mercy. I should not like to degrade the religion that I profess, nor to bring reproof upon thy Name; and, dear Lord, thou knowest I cannot be happy without having some sweet moments of intercourse with thee. How is it, then, that I should be so barren and cold, so hard and wandering, and that all my comforts and sweet feelings seem to go, and I am left to be in such a cold and indifferent frame?” Have you never been there? If you have not, I know who has; and the Lord has come with such a passage as this: “Trust in the Lord, and do good; so shalt thou dwell in the land, and verily thou shalt be fed.” Or, “They that trust in the Lord shall be as Mount Zion, which cannot be moved.” “Blessed is the man that trusteth in the Lord.” “Cursed be the man that trusteth in man and maketh flesh his arm.” Why, this staggers us. “Lord.” we say, “what is it to trust in thee? I should like to trust in thee; I want to trust in thee; tell me what it is. Did I not trust in thee, Lord, when I enjoyed thy presence and felt the power of thy love; when my soul was satisfied with the love and blood of the dear Redeemer, and I poured out my soul to him? Tell me, Lord, what it is to trust in thee, and enable me to do it; for I want to trust in thee.” And then, perhaps, such a portion as our text will come: “We have the sentence of death in ourselves, that we should not trust in ourselves, but in God which raiseth the dead;” and God begins to explain the mystery,—that though all those sweet frames, sweet feelings, sweet manifestations of mercy were his work, our trusting in them was the work of self; and the Lord will cut off this arm of self, and let us have no self of ours to bring before him, and thus make us know that our rest is in the Lord, as the God of salvation, and our boast in his confidence and not our own. And so “we have the sentence of death in ourselves, that we should not trust in ourselves.”

II. But we shall pass on to notice the design,—that this is to cut us off from all our self-trust.

“Why, then,” say you, “does it not make us miserable?” Miserable! Why, suppose you were a skilful surgeon, and went to see a patient, and the patient’s complaint was of that nature that it led him to deceptive views, and that he needed some painful operation to cure him. The operation would not be pleasant; but there is a needs-be for it. There are deceptive views,—I had almost said a state of derangement; and they need some very painful operations sometimes to cure them. And so, blessed be our God, he knows what poor, deranged creatures we are, and what false views we have, and what false movements we make; and, as Hart says in one of his hymns, we “Make e’en grace a snare.”

We turn to a wrong use the revelation God makes of his love, and, instead of trusting in the Lord, put our trust in our own management of what the Lord has done in us. And indeed I do not wonder at this being the case with some of God’s people; for the ministers tell them they must do it,—they must cultivate faith, and cultivate love, and cultivate hope, and cultivate confidence. When I hear men talk in this way, it sounds to me as though a farmer were to take a piece of barren ground in hand, and when he had brought his plough and his manure and harrow upon it, and begun to knock about and spread his manure, and so cultivate the land, some one were to get up and say to the land, “You must cultivate the plough; you must cultivate the harrow; you must cultivate the manure.” Why, would you not think the man crazy? It is the plough and the manure and the harrow that are to cultivate the land. And so it is our God that by the communication of his love to the conscience by the power of the Spirit is to cultivate our barren souls; and he will make, he says, the desert to rejoice and blossom as the rose. It is the Lord’s grace that is to cultivate us. And when we begin to cultivate, instead of, submitting to God’s cultivation, why, then the sentence of death must come upon it, “that we should not trust iii ourselves, but in God that raiseth the dead.”

I do not know whether you have felt it or not; but I solemnly have felt, in hundreds of instances, that I need this sentence of death to keep me from self-trust,—as a minister and in every stage that I have passed through in life. Sometimes I have been prone to think, “Now I have so many passages of Scripture turned down that have been very sweet to me when I have been reading them. I have them ready to preach from; I can turn to one of them when I choose, and go with my text and subject made ready, in order that the people may be benefited.” And when! have gone, there has been the sentence of death upon me; not a passage that would fit me, not a passage that I could fit. All my cultivation would not bring one passage into my conscience, nor my conscience into one passage. I have been as deathly and cold and unable to lay hold of a single passage of God s Word to come before the people with as I was the first moment that I was brought to speak in his Name; and sometimes I have been ready to think that I never did speak anything, and never shall be able. And I have to go, groaning and sighing and panting and crying; and what is worse than that, at times I really cannot groan, nor sigh, nor pant, nor cry. “O,” say you, “you must be a queer creature indeed.” Indeed I am; and that is just what I am; so that I can neither trust myself for praying, nor trust myself for preaching, nor trust myself for hoping, nor trust myself for confidence, I often tell the Lord to keep and to be with me; “for, Lord, thou knowest that I am neither fit to be trusted with myself, nor trusted in company, nor trusted anywhere; and I can put no confidence in myself in any sense whatever.”

Now, has the Lord brought you there? If he has, you have been necessarily weaned from self-trust. And yet you will get at it again. This cursed pride of ours, do what we may, will be making us in a measure pass by the Lord, and not trust in him. And all the cuttings up you have, all the harrowings of your feelings, all the death of your enjoyment and your comfort and your imaginary power to keep your peace and your happiness,—if you are a child of God, the Lord sees it all necessary to wean you from the cursed pride of trusting in yourselves, that there may be nothing but a sinner saved by the grace of God, and that Jesus may be glorified in the manifestation of his grace in saving your soul. And so we have the sentence of death in self, that we may not trust in self.

I tell you, brethren, do not you venture to trust yourselves anywhere, unless you can, in some small measure, find that you have been led to put your trust in God. Now I have known men be very inquisitive concerning other people’s practices, and be led to conclude they were not altogether walking very becomingly, and they have watched them cautiously that they might be able, as they thought, to give them seasonable rebuke and reproof; but they never dreamed that all the time in watching them they might create the same working in themselves, till it actually came, and they were in the very same snare, and felt that God had to give them a reproof; and thus cured them of self-trusting. And I would advise you, in the Name of the Lord, do not trust your eyes, do not trust your ears, do not trust yourselves, without the Lord being your Guide; for really we are not fit to be trusted for a moment. And so the Lord will bring us to have the sentence of death in ourselves, “that we should not trust in ourselves.”

III. Now, lastly, the great design is to bring us to trust “in God that raiseth the dead.” This is a blessed expression: “God that raiseth the dead.” He raised Christ from the dead; he raiseth us from our death in sin. He raised the dry bones in Ezekiel’s vision; and if you and I have had the sentence of death in ourselves, we have been there. We know how it was with those bones, when they were all distorted, and no bone seemed in its proper place, and there was neither flesh nor sinews; and when flesh and sinews came, and the judgment appeared to get hold of some truth, still there seemed to be no life and no motion, till the Spirit of God sent life. Therefore we know a little of what he can do in raising the dead.

“That we should not trust in ourselves, but in God.” Trust him for what? Trust him for pardon, manifested pardon, again and again. “But,” say you, “we do not want fresh pardon; for God pardons all at once.” But we want fresh manifestations of it. Suppose I were a farmer, and had my rick-yard full of stacks of corn, and my granary full, and my fields full of cattle, so that I had as much food as would last my family two or three years, could I sit down and say, “Now I want no bread-making and no cooking? I have plenty in the yard, and the granary, and the fields, and that is enough for me.” I should cut a poor figure with all my plenty; I should die, you know. The Lord has told us that there is fulness in Jesus Christ; but that is nothing for the poor soul, unless it has a little of the manifestation of it and enjoyment of it. If a hungry man, who has been working in the field for six or seven hours, comes in to sit down to a meal, and his master says, “Ah, well! You have done your work well; sit down. There is plenty of food in the barn and in the cupboard to last you for years; so be content.” “Yes,” Bays the man, “but I want to taste a little of it; knowing it is there is not enough.” And God’s people want to be feeling, and tasting, and handling of the Word of life. They do not want merely the judgment-knowledge of it,—that there is enough; they want the feeling enjoyment of it,—to have it brought into their consciences. They ask God for fresh communications of pardon, fresh Jottings down of peace into the conscience, fresh revelations of the glory of Christ and of their interest in him. And they are led to trust in the Lord for it. Trust in the Lord, says God, and thou shalt be established. “They that trust in the Lord shall be as mount Zion.” And thus the Lord puts us off from all self-trust, in order to bring us to a solemn and sweet trust in Christ for the blessed openings of this to the mind; that so we may be led to eat the flesh and drink the blood of the Lord Jesus Christ; without which we have no life in us. He does not say, “You must believe there is enough in me;” but there must be an eating and drinking, a spiritually entering into the vitality of H, by the power of that vitality entering into you. And I tell you, in the Name of the living God, that if God never gives you an entering into the vitality of this truth, as God lives you will be damned,—if the Lord the Spirit never gives you a vital experience of Divine truth in the conscience. If you are his people, he will bring you from all self-trust to trust in him for the vital manifestation of the mysteries of his cross to your soul; that you may know blessedly and vitally what it is to have the Lord for your strength and your succour and support.

“We have the sentence of death in ourselves, that we should not trust in ourselves, but in God,” to keep us in time of temptation. This was the case with David. Not when he was on the house-top. No, no, poor soul; but when he was brought to his right mind, he was brought feelingly and spiritually to say, “Hold thou me up, and I shall be safe.” “Keep back thy servant from presumptuous sins.” Why, David! Could you not hold yourself up, so famous a man as you, so much of the presence of God as you have enjoyed” And “presumptuous sins!” Is there any danger of a man of God like you, who have had such manifestations of Divine favour, getting into presumptuous sins? Aye, there was; and God convinced him of it by strange methods, till he was brought of necessity to know that his trust was in the Lord; and so he says, “Hold me up, and keep me back, Lord.” And so with poor Moses. When he had to lead Israel, he said, “If thy presence go not with us, carry us not up hence.” He felt himself incapable of managing either himself or the people.

Our trust, therefore, is in God, for strength to keep us in the hour of temptation, to keep us from the workings of in-bred corruption, the snares of the devil, and the allurements of the world; to keep us from all those bewitching things that are suited to flesh and blood. And we have to trust in the Lord for the opening of his promises and the mysteries of his love, in bringing again the sweet sense of the love of Christ, the blood of Christ, and the power of Christ into the heart, and leading us into it; so that there may be a sweet coming of Christ into us and a going out of self into Christ. May you be enabled to trust in Christ, then, poor soul, if you want real comfort and real support.

“But,” says some poor soul, “how dare I venture to trust in the Lord when I have such a dead heart and conscience?” Do you not see, poor soul, it is “God that raiseth the dead?” He raises us again out of those deathly frames and feelings that we have to go through. And there is no saying what the Lord cannot do, poor creature. He can come into the deepest depth of thy death and wretchedness, and lift thee out of it all, and lift thee into himself.

May God bless you and me with a feeling sense of solemn confidence in him.

Amen, and amen.

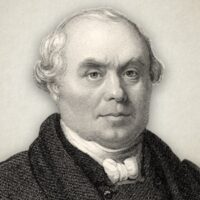

William Gadsby (1773-1844) was a Strict and Particular Baptist preacher, writer and philanthropist. For thirty-nine years served as pastor for the church meeting at Black Lane, Manchester.

William Gadsby Sermons (Complete)

William Gadsby Hymns

William Gadsby, Perfect Law Of Liberty (Complete)

William Gadsby's Catechism (Complete)

William Gadsby's Dialogues

William Gadsby's Fragments (Complete)

William Gadsby's Letters (Complete)