Introduction

Clifford Pond served in the pastoral ministry among Grace Baptist churches for more than 50 years. Having seen the need for congregations to better understand the complexities of adopting a plurality of elders, he wrote a book entitled “Only Servants.” The back cover of the book offers a reason why the author is a respected authority on the subject: “Clifford Pond writes out of a lifetime of pastoral ministry, having served churches in Suffolk and Surrey as well as exercising a wider ministry at various times by responsible leadership in young people’s fellowships, associations of churches and the council of Grace Baptist Mission.”

In the fifth chapter, under the heading “Plurality of Elders and Deacons”, Mr. Pond writes:

“Since the Second World War every part of life generally has been questioned, and churches too have been put under the scrutiny of Scripture…For example, in the earlier part of this century the most common structure in local churches was a pastor with a group of deacons. In the absence of a pastor the church secretary often became the leader; but now this arrangement is being seriously questioned and the most significant change has been towards a plurality of elders. These changes have caused an upheaval in many churches, and troubled members have asked ‘Were the people in the past so wrong? We respected them and the Lord blessed their ministry, how can it be that they were so wrong at this point?’”[1].

Himself an advocate of elder plurality, Mr. Pond highlights three important facts which remain at the forefront of this subject:

1. The common (historic) structure in local churches has been a pastor with a group of deacons.

2. The adoption of elder plurality in local churches picked up momentum after the Second World War.

3. The change has caused an upheaval in many churches, and troubled members are asking, “Were the people in the past so wrong? We respected them and the Lord blessed their ministry, how can it be that they were so wrong at this point?”

Church members have the right, yea, even the duty to ask these questions. The adoption of a plural eldership significantly changes the way Baptist churches inherently function,[2] and therefore every baptised believer should make it a matter of priority to understand the scriptural teaching on the subject. Prior to searching the Scriptures for answers, it is helpful to frame the subject in a contemporary context. This will not only enable the reader to understand the process which led many Baptist churches to adopt a plural eldership, but it will also introduce the reader to the divergent views advanced by plural eldership advocates.[3]

The Historical Context

Despite claims to the contrary,[4] the subject of elders in the early churches does not appear to have been a subject of concern for Baptist churches until the mid 19th century.[5] However, even at this relatively late date, only a handful of writers toyed around with the idea, and a close examination of their views do not exactly resemble those of present day Reformed Baptists.[6] In addition, only a few churches actually adopted the new order of a plural eldership.[7] Up until the 1950’s, Baptist churches were invariably overseen by a pastor, whose ministry was supported by a group of deacons.[8] The consensus among the early Baptists was that the terms ‘elder’, ‘bishop’ and ‘pastor’ were interchangeable titles identifying the same office,[9] and that each church would naturally appoint one pastor as overseer.[10] The title ‘bishop’ was seldom used, probably because of the connotations with Catholicism; the title ‘elder’ was more frequently used in the 16th and 17th centuries; the title ‘pastor’ appears to have been adopted from the 18th century onwards.[11]

A Typical Baptist Church

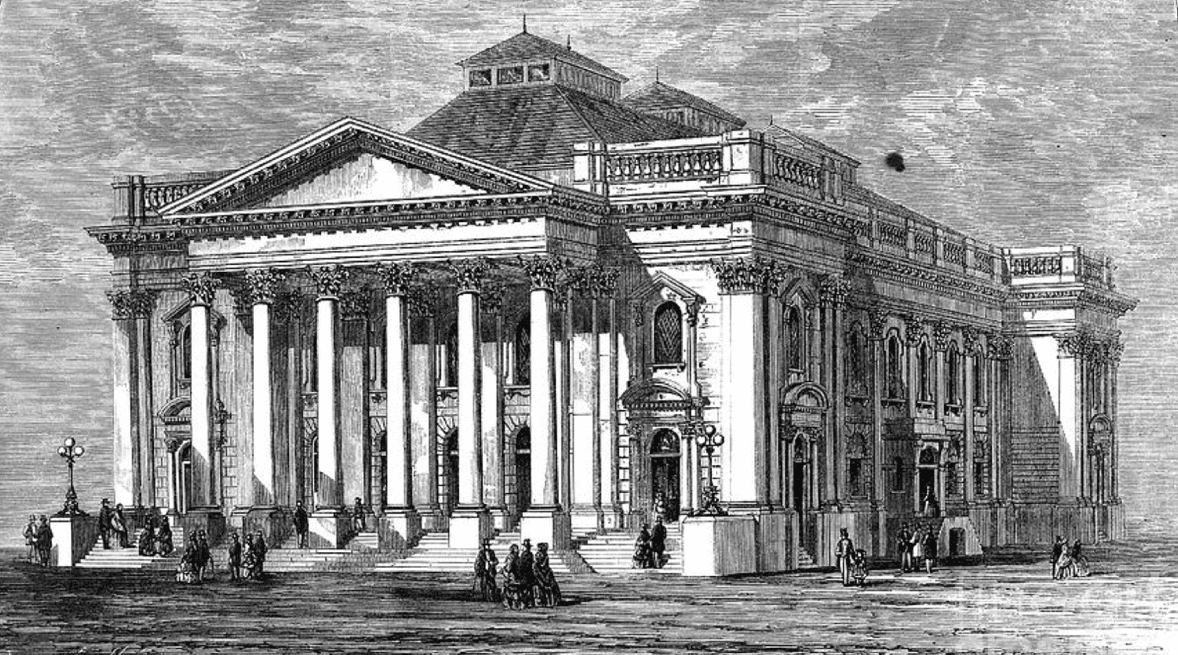

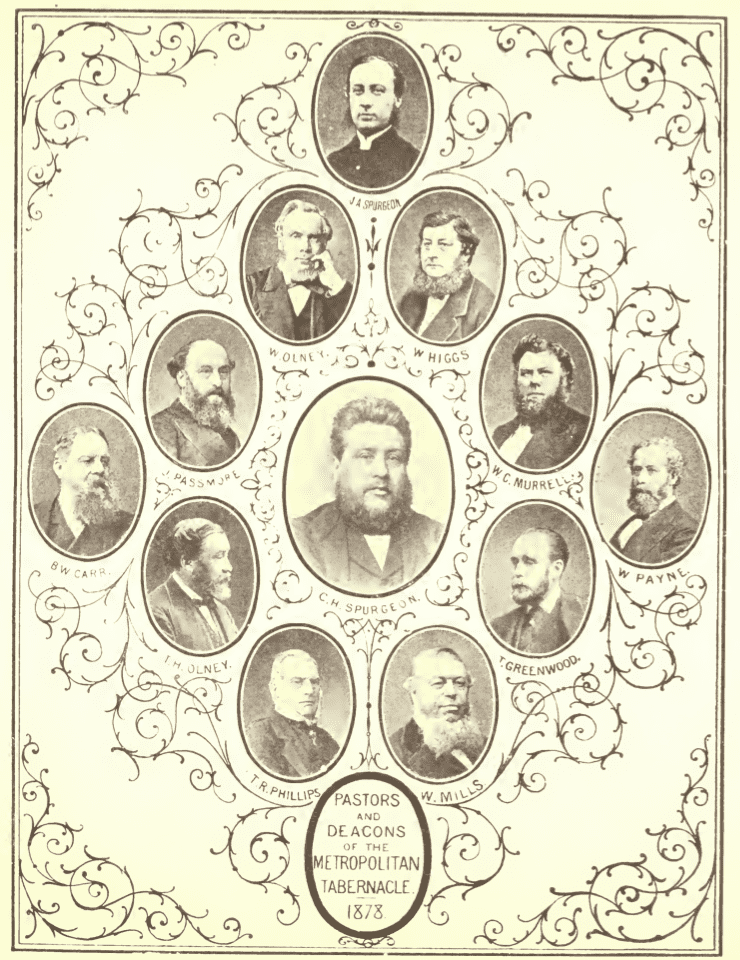

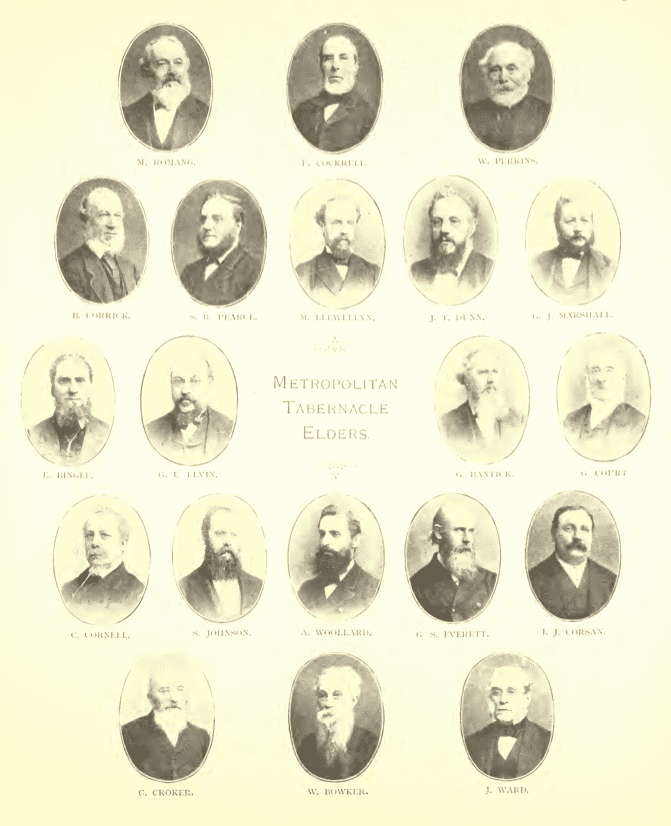

To follow the trail of evidence on how churches were historically governed and when they began to adopt a plural eldership, it is helpful to take a snapshot of a typical Baptist church.[12] The Metropolitan Tabernacle in London, would serve this purpose well. First, because this is the most famous Baptist church in recent history and many contemporary congregations look to it as a model for their own faith and order. Second, because this church is one of the oldest Baptist congregations in London, offering a helpful overview on how the church has been governed over the course of more than 360 years. Third, because the church has been overseen by three of the leading Baptist pastors of their generation, representing three centuries—John Gill (18th century), Charles Spurgeon (19th century) and Peter Masters (20th century). Fourth, because this is arguably one of the first churches to adopt a plural eldership.

First, because this is the most famous Baptist church in recent history and many contemporary congregations look to it as a model for their own faith and order. Second, because this church is one of the oldest Baptist congregations in London, offering a helpful overview on how the church has been governed over the course of more than 360 years. Third, because the church has been overseen by three of the leading Baptist pastors of their generation, representing three centuries—John Gill (18th century), Charles Spurgeon (19th century) and Peter Masters (20th century). Fourth, because this is arguably one of the first churches to adopt a plural eldership.

Quoting from Thomas Crosby, Charles Spurgeon points out that the Tabernacle congregation “had formerly belonged to one of the first ancient congregations of the Baptists in London, but separated from them in the year 1652, for some practices which they judged disorderly, and kept, together from that time as a distinct body.”[13] The congregation having first met in private houses, it wasn’t until the second pastorate, held by Mr. Benjamin Keach, that the church erected its first meeting-house, capable of holding approximately a thousand hearers.[14] In 1757, Under the ministry of its fourth pastor, held by John Gill, the church erected a new-meeting house near London Bridge.[15] In 1830, under the ministry of its fifth pastor, held by John Rippon, the church began to erect a new building, located on New Park Street.[16] In 1861, under the ministry of its ninth pastor, held by Charles Spurgeon, the church moved to a newly erected chapel which houses the congregation to this day.[17] Although the church was overseen by 20 pastors during its notable history,[18] there were three men of particular note that will serve to illustrate the evolution of plural eldership in the Tabernacle.

1. John Gill—The Strict Baptist Theologian (18th Century)

John Gill was an 18th century English Baptist theologian and pastor. He died when he was 73 years old, having lived between 1697 and 1771. At the age of 22, he became pastor of the Strict Baptist church at Goat Yard Chapel (Metropolitan Tabernacle), and remained in this one ministry for 51 years. Gill is arguably one of the greatest Baptist theologians, whose influence continues to this day, largely because of his prolific written ministry. He has bequeathed to the world a comprehensive commentary on the Old and New Testaments which comments on every verse of the Bible.

At the age of 22, he became pastor of the Strict Baptist church at Goat Yard Chapel (Metropolitan Tabernacle), and remained in this one ministry for 51 years. Gill is arguably one of the greatest Baptist theologians, whose influence continues to this day, largely because of his prolific written ministry. He has bequeathed to the world a comprehensive commentary on the Old and New Testaments which comments on every verse of the Bible.

In his notes on 1 Timothy 5, Gill rejects the interpretation forced on the text by John Calvin,[19] but nevertheless accepts Calvin’s assertion that the elders of verses 17 and 19 refer to the officers of a church. Note how Gill interprets the term ‘elder’ at the beginning of the chapter (verse 1), then jumps to a spurious interpretation of the same term towards the end of the chapter:

Ver. 1. Rebuke not an elder, etc. By whom is meant, not an elder in office, but in age; for elders by office are afterwards spoken of, and particular rules concerning them are given, (1 Tim 5:17,19). Besides, an elder is here opposed, not to a private member of a church, but to young men in age; and the apostle is here giving rules to be observed in rebuking members of churches, according to their different age and sex, and not according to their office and station…but though this is the sense of the passage, yet the argument from hence is strong, that if an elder in years, a private member, who is ancient, and in a fault, is not to be roughly used, but gently entreated, then much more an elder in office.

Ver. 17. Let the elders that rule well, etc. By whom are meant not elders in age…the elders here are particularly described as good rulers and labourers in the word and doctrine; besides, elders in age are taken notice of before…nor are lay elders meant, who rule, but teach not; since there are no such officers appointed in the churches of Christ; whose only officers are bishops or elders and deacons: wherefore the qualifications such are only given in a preceding chapter…these are called “elders”, because they are commonly chosen out of the senior members of the churches, though not always, Timothy is an exception to this.”[20]

Gill correctly interpreted the term ‘elder’ in verse 1 as referring to persons of age, rather than office; yet, he violates his own exegesis when imposing on the same term in verses 17 and 19, the premise of the Presbyterians—that the term elder refers to church officers. Nevertheless, he flat out rejects the distinction between two types of elders (ruling and teaching). Gill viewed the term elder as synonymous with the office of bishop, which meant that only those divinely gifted for the work of preaching were responsible for the work of overseeing. Attention should also be given that he makes no mention of a plurality of elders in a single church.[21] As already noted, it was the custom of Baptist churches during the 18th century to install one pastor as overseer, assisted by a group of deacons.

2. Charles Spurgeon—The Reformed Baptist Forerunner (19th Century)

Charles Spurgeon, nicknamed the “Prince of Preachers”, requires little introduction. He served as pastor for 38 years, between 1854 and 1892. His remarkable gifts of oratory attracted crowds in excess of 10,000 people on occasions. He founded a pastors’ college, an orphanage, a Christian literature society and The Sword and the Trowel magazine. He was the author of many books and pamphlets, the most popular being those of his printed sermons filling 62 volumes. In his Autobiography, compiled by his wife after his death, Spurgeon offers the following account on the installation and function of ‘elders’ at the Tabernacle:[22]

His remarkable gifts of oratory attracted crowds in excess of 10,000 people on occasions. He founded a pastors’ college, an orphanage, a Christian literature society and The Sword and the Trowel magazine. He was the author of many books and pamphlets, the most popular being those of his printed sermons filling 62 volumes. In his Autobiography, compiled by his wife after his death, Spurgeon offers the following account on the installation and function of ‘elders’ at the Tabernacle:[22]

“When I came to New Park Street, the church had deacons, but no elders; and I thought, from my study of the New Testament, that there should be both orders of officers. They are very useful when we can get them,—the deacons to attend to all secular matters, and the elders to devote themselves to the spiritual part of the work; this division of labour supplies an outlet for two different sorts of talent, and allows two kinds of men to be serviceable to the church; and I am sure it is good to have two sets of brethren as officers, instead of one set who have to do everything, and who often become masters of the church, instead of the servants, as both deacons and elders should be.

As there were no elders at New Park Street, when I read and expounded the passages in the New Testament referring to elders, I used to say, “This is an order of Christian workers which appears to have dropped out of existence. In apostolic times, they had both deacons and elders; but, somehow, the church has departed from this early custom. We have a preaching elder,—that is, the Pastor,—and he is expected to perform all the duties of the eldership.” One and another of the members began to enquire of me, “Ought not we, as a church, to have elders? Cannot we elect some of our brethren who are qualified to fill the office?” I answered that we had better not disturb the existing state of affairs; but some enthusiastic young men said that they would propose as the church-meeting that elders should be appointed, and ultimately we did appoint them with the unanimous consent of the members. I did not force the question upon them; I only showed them that it was Scriptural, and then of course they wanted to carry it into effect.”

The church-book, in its records of the annual church-meeting held January 12, 1859, contains the following entry:—[23]

“Our Pastor, in accordance with a previous notice, then stated the necessity that had long been felt by the church for the appointment of certain brethren to the office of elders, to watch over the spiritual affairs of the church. Our pastor pointed out the Scripture warrant for such an office, and quoted the several passages relating to the ordaining of elders: Titus 1:5, and Acts 14:23;—the qualifications of elders: 1 Timothy 3:1-7, and Titus 1:5-9;—the duties of elders: Acts 20:28-35, 1 Timothy 5:17, and James 5:14; and other mention made of elders: Acts 11:30; 15:4,6,23; 16:4, and 1 Timothy 4:14.

Whereupon, it was resolved, that the church, having heard the statement made by its Pastor respecting the office of the eldership, desires to elect a certain number of brethren to serve the church in that office for one year, it being understood that they are to attend to the spiritual affairs of the church, and not to the temporal matters, which appertain to the deacons only.”

Spurgeon continued with his account on the election and function of elders:[24]

“I have always made it a rule to consult the existing officers of the church before recommending the election of new deacons or elders, and I have also been on the look-out for those who have proved their fitness for office by the work they have accomplished in their private capacity. In our case, the election of deacons is a permanent one, but the elders are chosen year by year. This plan has worked admirably with us, but other churches have adopted different methods of appointing their officers. In my opinion, the very worst mode of selection is to print the names of all the male members, and then vote for a certain number by ballot. I know of one case in which a very old man was within two or three votes of being elected simply because his name began with A, and therefore was put at the top of the list of candidates.

My elders have been a great blessing to me; they are invaluable in looking after the spiritual interests of the church. The deacons have charge of the finance; but if the elders meet with cases of poverty needing relief, we tell them to give some small sum, and then bring the case before the deacons. I was once the unseen witness of a little incident that greatly pleased me. I heard one of our elders say to a deacon, “I gave old Mrs. So-and-so ten shillings the other night.” “That was very generous on your part,” said the deacon. “Oh, but!” exclaimed the elder, “I want the money from the deacons.” So the deacon asked, “What office do you hold, brother?” “Oh!” he replied, “I see; I have gone beyond my duty as an elder, so I’ll pay the ten shillings myself; I should not like ‘the Governor’ to hear that I had overstepped the mark.” “No, no, my brother,” said the deacon; “I’ll give you the money, but don’t make such a mistake another time.”

Spurgeon freely admitted, prior to his installation of a plural eldership, that the Tabernacle had only ever been overseen by a pastor with deacons.  It is noteworthy that Spurgeon leaned heavily upon the ideas espoused by John Calvin in his interpretation of 1 Timothy 5—that there should be two orders of elders (teaching and ruling).

It is noteworthy that Spurgeon leaned heavily upon the ideas espoused by John Calvin in his interpretation of 1 Timothy 5—that there should be two orders of elders (teaching and ruling).  However, it must also be noted that Spurgeon’s view on how elders were to function in a church were very different from the way many Reformed Baptists go about it today—(1) he enforced the policy that he and the deacons held a permanent office, whereas the elders had to be reelected each year; (2) he also created a system where he made himself the head, the deacons the right hand and the elders the left hand—and he tells the story about how he, the head (pastor, or ‘governor’ as he liked to be called), watched how his right hand (deacons) knew not what his left hand (elders) did, and when his right hand found out about it, it slapped the left hand for doing what only the right hand was permitted to do. In fact, Spurgeon designed the offices in the Tabernacle to reflect the function of this bureaucratic hierarchy, for he writes,

However, it must also be noted that Spurgeon’s view on how elders were to function in a church were very different from the way many Reformed Baptists go about it today—(1) he enforced the policy that he and the deacons held a permanent office, whereas the elders had to be reelected each year; (2) he also created a system where he made himself the head, the deacons the right hand and the elders the left hand—and he tells the story about how he, the head (pastor, or ‘governor’ as he liked to be called), watched how his right hand (deacons) knew not what his left hand (elders) did, and when his right hand found out about it, it slapped the left hand for doing what only the right hand was permitted to do. In fact, Spurgeon designed the offices in the Tabernacle to reflect the function of this bureaucratic hierarchy, for he writes,

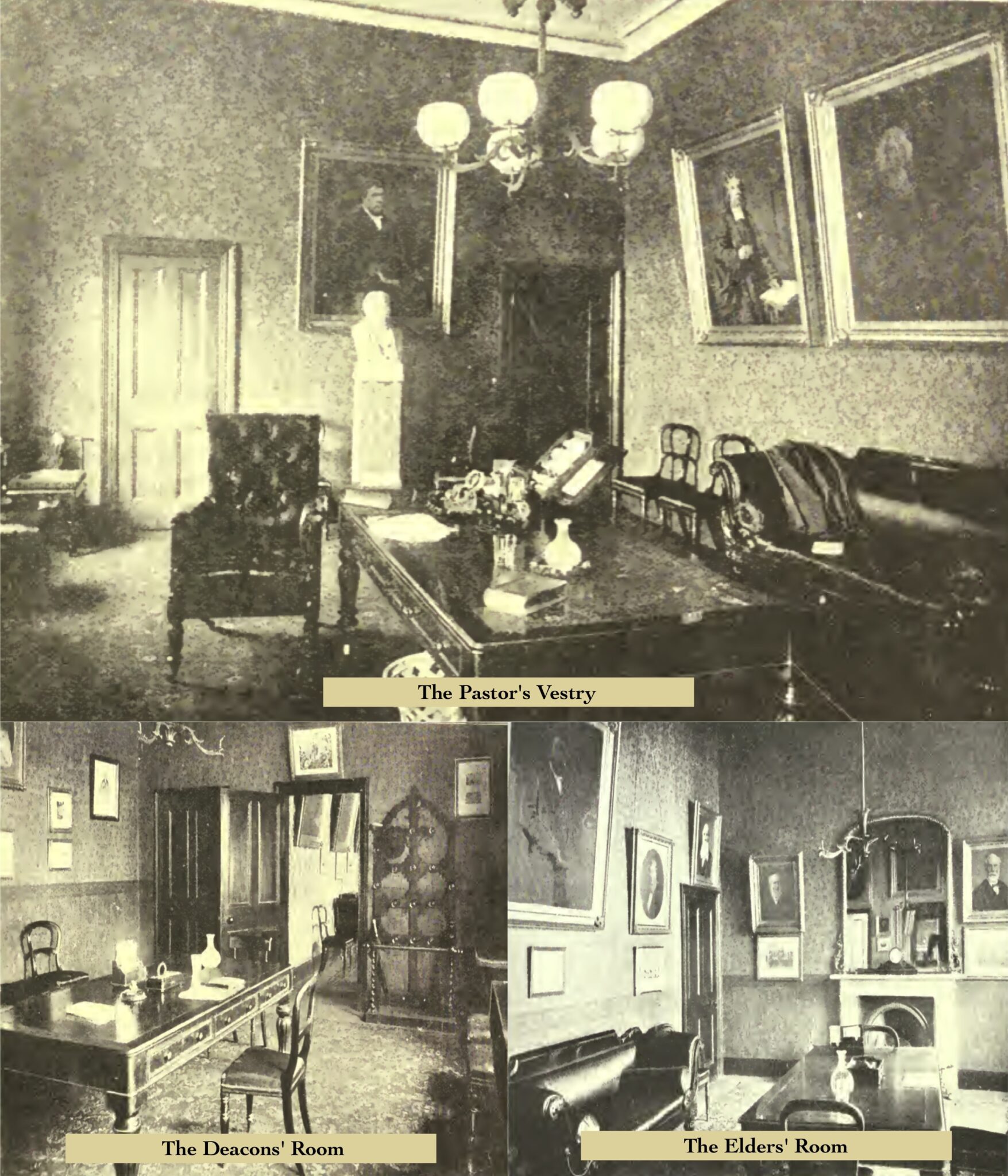

“Behind the upper platform, there are three spacious rooms; in the centre, is the minister’s vestry; to the right and left, are the rooms of the deacons and elders,—the officers of the army on either side of the captain, so that they may be ready to go forward at the word of command. Then above them, on the third story, there are three other excellent rooms, to be used for tract and Bible depositories, and for other schemes which we hope the church will undertake.”[25]

Thus, we discover Spurgeon introducing a system of church government, not before practiced or recognized by the church, and indeed functioning very different from what many Reformed Baptists today conceive it to be. Nevertheless, Spurgeon may well be regarded as the forerunner of the Reformed Baptists. For he not only introduced a new type of church government, but he also embraced the philosophy of Fullerism[26] and practiced a more open Communion Table.[27] Spurgeon may also be credited with the modern day trend of building mega churches. Few things have been more destructive to the function and life of churches than the extravagant size of a single congregation. In fact, it was because of the enormous size of his congregation, running into the thousands, that Spurgeon introduced something that was completely foreign to his church—a plural eldership. In my experience, the arguments for a plural eldership are rooted in the practicalities of the system,[28] followed by a feeble attempt to authenticate the arrangement with Scriptural support; it is a polity read into the Scriptures, not drawn from it.

3. Peter Masters—The Reformed Baptist Advocate (20th Century)

Dr. Peter Masters has been the pastor of the Metropolitan Tabernacle for 43 years (since 1970). He has been instrumental in building up the congregation which now stands as one of the largest Reformed Baptist churches in the country. He is also the author of several books. With reference to this subject on elders, I now quote from an article written by Dr. Masters for the Sword and the Trowel, 1985, No. 2, pp 24,25:

“A new generation of church constitutions insist that the elders rule in absolute ‘parity’. The unique role of a pastor as the presiding and preaching elder is swept away by this arrangement (though happily, some congregations continue to clothe the full-time elder with the more biblical status of ‘pastor’ because the members have not really understood the new system!). We must make it clear that this modern system is quite different from the traditional Reformed position which recognises three kinds of officer; (1) the minister or pastor as the preaching elder. (In larger churches there could be more than one.) (2) the ruling elders. These are assisting, shepherding elders exercising a ministry of teaching and counselling other than the public ministry of the Word, and sharing the work of discipline and care with their pastor, who is the presiding elder. (3) Deacons.—This is the viewpoint adopted by the Reformed tradition historically and is the position held by our Presbyterian brethren.”

And indeed, when you compare this view with that of Gill and Spurgeon, it is clear which of the two Dr. Masters favours. He is espousing, not the historic view maintained by John Gill, but the ‘reformed’ view introduced by Charles Spurgeon. Herein is a three-tier order of church officers, that of pastor(s), elders and deacons, rather than the traditional two-fold grouping of pastor and deacons. If Spurgeon was the forerunner to the Reformed Baptist movement,[29] then Dr. Masters has been one of its leading proponents in the 20th century.[30] Dr. Masters is to be commended for giving credit to our Presbyterian brethren, because it is to them the Reformed Baptists must return for their system of plural eldership.

The Other Group of ‘Reformed Baptists’

It should be noted, as Dr. Masters pointed out, that there are many Reformed Baptists that claim elders are one and the same with bishops and pastors. Dr. Mark Dever, Nine Marks of a Healthy Church, Chapter 10, distinguishes between the Presbyterian and Reformed Baptist view of eldership by rejecting the distinction made by the former group between ruling and teaching elders. He remarks,

“Presbyterians have tended to stress Paul’s statement to Timothy in I Timothy 5:17…this is the origin of the distinction between “ruling elders” (lay elders) and “teaching elders” (ministers)…Baptists have tended to stress the interchangeability of the terms “elder,” “overseer,” and “pastor” in the New Testament.”

Yet, a couple of paragraphs later he remarks,

“This does not mean that the pastor has no distinctive role. There are many references in the New Testament to preaching and preachers that would not apply to all the elders in a congregation…We must, however, remember that the preacher, or pastor, is also fundamentally one of the elders of his congregation.”

So, in theory Dr. Dever rejects Spurgeon’s and Dr. Master’s notion of making a distinction between the elders and the pastor(s), yet in practice he makes a clear distinction between the ‘pastor(s)’ and other ‘elders’, though he had previously stated they are one and the same. This is typical of the plural elder ideology—while Reformed Baptists insist each church should have a plurality of elders, there does not exist a clear and consistent definition on exactly who they are and how they function.

The Evolution of Error

Emerging from the foregoing case study are two groups of Reformed Baptists advocating a plural eldership—those who believe the title elder identifies two different types of leaders (teaching and ruling elders), and those who believe the titles bishop, pastor and elder are used interchangeably to identify the same office. Both groups insist each church should be overseen by a plurality of elders, however the term elder might be defined. Although the view of both groups can be traced back to the teachings of John Calvin on 1 Timothy 5:17, it should be noted that the first group appears to be more heavily influenced by Calvin than the second group—for they distinguish between teaching and ruling elders. On the other hand, the second group appears to take a more ‘baptistic’ approach to elders by building on the view of John Gill.[31] Notwithstanding Gill’s practice in serving as the only pastor of his congregation, he unwittingly established the basis on which the second group of Reformed Baptists built their plural eldership ideology. For by making the term ‘elder’ synonymous with the terms ‘bishop’ and ‘pastor’,[32] it is argued that as the term elders appears invariably in the plural throughout the New Testament, it is prudent, if not necessary, for every church to install a plurality of elders (pastors) to oversee the congregation.

The argument can be summarised under four headings:

1. The term ‘elder’ is synonymous with the terms ‘bishops’ and ‘pastors’.

2. Since these titles—elder, bishop, pastor—are synonymous, virtually every Scriptural reference to ‘elders’ in the early churches must refer to that office.

3. As the term ‘elder’ regularly appears in the plural, it is evident each church was overseen by a plurality of elders, thereby establishing a clear pattern on how the early churches functioned.

4. This pattern of plural elderships in the early churches is sufficient grounds on which to assume it is a divinely appointed prescription that every successive church should seek to adopt.

It is in this vein Clifford Pond frames his case for a plural eldership:

“What is the biblical evidence that local churches should be led by a plurality of elders assisted by a body of deacons?

A comparison of Scripture with Scripture reveals that the terms pastor, elder and overseer (bishop in some versions) describe different aspects of the same ministry within the church (Acts 14:23; 20:17-28; Philippians 1:1; 1 Timothy 3:1-13; Titus 1:5-9; 1 Peter 5:1-4). The term pastor suggests shepherding and loving-care in terms of teaching, counselling and correcting. Elder—indicates maturity in experience of life and in the application of Scripture to life. Overseer—suggests responsibility and authority though answerable to a higher authority.

Wherever in the New Testament these leaders are mentioned it is always in the context of local churches, and the reference is always to a group of elders or a group of deacons. There is never a suggestion that there would normally be only one elder or one deacon.”[33]

It is my contention, which will be laid out in the pages of this book, that the above line of argument for a plural eldership is based on a false hermeneutic, followed by an incorrect deduction and ending with an erroneous conclusion.

The Challenge of this Book

The Apostle Paul warned the bishops in Ephesus that grievous wolves would rise up even among themselves. Such has been the case in Baptist churches—within our own ranks, men professing to carry the Baptist banner have been wearing the undergarments of Presbyterianism. Now, if these leaders chose to organize a new group of churches representing their hybrid views, this would be perfectly acceptable, if not respected. But instead, they have sought to hijack the historic faith of our Strict and Particular Baptist churches, attempting to legitimatize their Reformed Baptist movement by laying claim to a proud lineage of Baptist forefathers. By and large, Strict Baptist churches have forsaken their historic values, largely because they have been commandeered by the Reformed Baptists.

Make no mistake, Reformed Baptists have launched a frontal attack against the Strict Baptists,[34] particularly in the type of leadership responsible for overseeing each church. They demand their way is more biblical—a return to primitive Christianity—having arrived at a special enlightenment of the Scriptures to which our forefathers were blinded or ignorant. This cannot go unanswered. They must be held accountable for the damage they have incurred among the historic churches and Baptists must be able to discard the misleading information propagated by their movement. It is time for Strict Baptists to take a stand for their values and refuse to give any further ground to those who seek to pervert/uproot it. There is not a more urgent subject facing Baptist churches today than the issue of biblical leadership.

To be clear, the dispute this book seeks to explore is not over the existence of elders in the early churches, for on this point all parties are agreed. The issue, rather, is over the identity of these elders. Regardless of the divergent theories on a plural eldership among the Reformed Baptists, in practice, they all function according to a three-tier hierarchical system—pastor(s), elders and deacons. This is a bureaucratic entanglement which not only complicates the simplicity of Baptist polity, but also infringes on the liberty of the priesthood of all believers. This ‘big government’ take over cannot be sustained scripturally or easily maintained practically. The Reformed Baptists is a powerful movement claiming to reform churches to the New Testament, when in reality they are conforming churches to their newfangled theory of ‘Presbygationalism’[35]—far from returning them to the New Testament model, they are transforming them into a hybrid of Presbyterian/Baptist churches.[36] John Gill did not advocate this model nor would he do so if living today. He and his forbearers may have incorrectly identified the elders (to be synonymous with bishops/pastors), but at least they did not develop the error as have done our Reformed Baptist brethren by creating a monstrous oligarchy in the church of Christ.[37]

I opened with a quote from Clifford Pond, and it is fitting I close with another from the same author. After admitting the adoption of a plural eldership in Baptist churches had “caused an upheaval”, and “troubled members” began to question the serious change in Baptist polity, Mr. Pond continued in the next paragraph:

“Such questions are understandable and we must always beware of change for change’s sake, or simply to be in the fashion. The Lord blesses us despite our imperfections, and no generation has a complete understanding of any aspect of biblical truth. It is no disrespect to godly people in the past for us today to follow Scripture, wherever that leads us, for to do so is to submit to the Lord himself.”[38]

In the same spirit, this book seeks to shirk off the clothing of tradition and presupposition, stepping back into the world of the prophets and apostles, seeking to understand how they would have used the term ‘elder’. It is with great trepidation we depart from the views of men such as John Gill, but I remind the reader that the conclusion arrived at in this book advances the same conclusion as that of Gill—that each church should be overseen by one pastor, assisted by a group of deacons—it is how one arrives at this conclusion that ultimately silences the opponents.

——————————-

[1] Clifford Pond, Only Servants, Page 32.

[2] See chapter 7 in “The Fallacy of Eldership: A Scriptural Analysis”.

[3] “The Fallacy of Eldership: An Historical Analysis”, will comprise a fuller statement on the history of plural elderships in Baptist churches (this work is yet to be published).

[4] Mark Dever argues that Baptist churches have historically recognised plural elderships and seeks to encourage them to return to the old paths, Nine Marks of a Healthy Church, Chapter 10.

[5] Douglas Weaver, points out: “In the 1950’s, a renewed interest in Reformed theology developed in England…Reformed Baptists also used elders whereas Strict Baptists preferred congregational polity. While both groups believed that their church order followed the divine pattern of the New Testament church, the two Calvinistic groups never united.” “In Search of the New Testament Church: The Baptist Story, Page 224 (Mercer University Press, 2008).

[6] Robert Wring expounds a number of 19th century Baptist writers in his ‘Dissertation Submitted to the Doctor of Philosophy Committee of the Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary’, 2002. Some of these writers are: W. B. Johnson, (1848) “A Church of Christ with Her Officers, Laws, Duties, and Form of Government: A Sermon”; J. L. Reynolds (1849), “Church Polity of the Kingdom of Christ in Its Internal and External Development” (“Polity: Biblical Arguments on How to Conduct Church Life”, Mark Dever (2001)); William Williams, “Apostolical Church Polity”, (1874), (“Polity: Biblical Arguments on How to Conduct Church Life”, Mark Dever (2001)); J. M. Pendleton (1882), “Distinctive Principles of Baptists”. In addition to these American writers, see also the remarks of the English Baptist writer William J. Styles, (1902) “A Guide to Church Fellowship”.

[7} For example, Little Prescott Street Chapel installed a set of elders in 1852, whose particular service was to visit the members divided into regional districts and regularly report to the pastor and deacons—these elders were not elevated to the same status extended to elders in Reformed Baptist churches today (see Earnest Kevan, “London’s Oldest Baptist Church”, Pages 147,148). Again, Metropolitan Tabernacle installed a set of elders during the ministry of Charles Spurgeon, but more is said on this point later in this introduction.

[8] Clifford Pond, Only Servants, Pages 21 and 32.

[9] Robert Wring, an Article published for the Association of Historic Baptists, Dec 11, 2011. Herein he sets forth the representative views of the early Baptists regarding the officers of the church. Part of his article states: “The First London Confession of 1644/46 and the Second London Baptist Confession of Faith of 1677/89 are no doubt the two most influential Confessions of faith in existence. These confessions hold much weight in any discussion of Church Polity. Both can be found in Lumpkin’s Baptist Confessions of Faith. (1) The First London Confession. On page 166 of the First London Confession, in Article XXXVI, the subscribers tell us that the church chooses its officers and they are called “Pastors, Teachers, Elders, Deacons.” Note (a) at the bottom of the page states that “Pastors and Teachers” are omitted in later editions. This is no doubt because Baptist leaders began to understand that the word “elder” was a title for the pastoral and teaching office. The elders were the pastors and teachers in the church. The elder(s) were God called men who were chosen by the local Baptist church to be their pastor and teacher. Under Article XXXVII, on page 166, the writers of the Confession mention “the ministers aforesaid” which in the context of the Confession refers to none other than the “Pastors, Teachers, Elders” of Article XXXVI. These men are called by the church where they serve to administer the ordinances and to carefully feed the flock committed to their charge. I submit to you that there is no other interpretation we should accept than the one that promotes the understanding that elders, pastors and teachers were the same men. We know them today as the pastor(s) of our churches. Under Article XXXVIII, on page 166, mention is again made to the “Officers aforesaid.” These officers were to preach the Gospel and live the Gospel. Additionally, these Officers (pastor/elders) were to be paid in some way by the church in which they served. (2) The Second London Confession. Under Chapter XXVI, Number 8, the subscribers state that the officers of the church are “Bishops or Elders and Deacons.” We are told that these men are appointed by Christ to be chosen and set apart by the church to serve in their office. The bishop/elders and the deacons are to administer the ordinances and execute Power or Duty among the members of the church. In Number 9 the pastoral church officer is called the Bishop or Elder of the church. In Number 10 the work of the Elder is called “the work of pastors.” Afterward their work is defined as “the ministry of the Word and prayer with watching for” the souls of their congregation. In Article 11, the elders are called “Bishops and Pastors.” Within the context of Chapter XXVI of the Second London Confession of Faith we see the names of the pastoral officers of a Baptist church in the day in which it was written. Therefore there can be no other conclusion than that the pastors of the churches in the 16th and 17th centuries were interchangeably called bishop/elder/pastor and deacons. This was the conclusion of the subscribers of this confession and they give their biblical basis for this affirmation next to each of the paragraphs dealing with the pastoral office under Chapter XXVI.”

[10] The Strict Baptist Historical Society has on record the individual ‘articles of faith and rules’ of many churches dating between the 17th to 20th centuries. I have examined more than 40 such documents and they rarely mention the term ‘elder’—with the exception of two or three statements dated after the 1950’s, every other statement invariably sets forth the church order of pastor and deacons.

[11] However, there are historic Baptist churches, particularly in the United States (Primitive Baptists), who insist on using the term ‘elder’ when referring to a pastor as it is felt to be a more biblically used term for that office.

[12] There does not appear to be a single Baptist church responsible for introducing a plural eldership. Rather, variant forms of a plural eldership were introduced by different churches throughout the centuries, but on each occasion, this form of church order was an exception to the rule (pastor and deacons). Therefore, selecting one of these ‘exceptional’ cases will sufficiently illustrate the typical way a plural eldership arose and developed in Baptist churches.

[13] C. H. Spurgeon, The Metropolitan Tabernacle: Its History and Work, 1876, p 16.

[14] Located at Goat’s Yard Passage, Fair Street, Horse-lie-down, Southwark.

[15] Located at Carter Lane, St. Olave’s Steet, Southwark.

[16] The building was completed in 1838 and it was this chapel that housed the congregation when Charles Spurgeon became pastor. In his book, “The Metropolitan Tabernacle: Its History and Work”, he offers the following description on page 56: “New Park Street is a lowlying sort of lane close to the bank of the river Thames, near the enormous breweries of Messrs. Barclay and Perkins, the vinegar factories of Mr. Potts, and several large boiler works. The nearest way to it from the City was over Southwark bridge, with a toll to pay. No cabs could be had within about half-a-mile of the place, and the region was dim, dirty, and destitute, and frequently flooded by the river at high tides. Here, however, the, new chapel must be built because the ground was a cheap freehold, and the authorities were destitute of enterprise, and would not spend a penny more than the amount in hand. That God in infinite mercy forbade the extinction of the church is no mitigation of the shortsightedness which thrust a respectable community of Christians into an out-of-the-way position, far more suitable for a tallow-melter’s than a meeting-house. The chapel, however, was a neat, handsome, commodious, well-built edifice, and was regarded as one of the best Baptist chapels in London.”

[17] Located at Elephant & Castle, London, SE1 6SD. However, the building itself has been rebuilt twice: (1) A fire completely destroyed the edifice in 1898 (leaving only the front portico and basement salvageable); (2) A bomb destroyed the building during the Second World War in 1941 (leaving again the front portico and basement salvageable). The present chapel was rebuilt in 1957 following a different design from the original.

[18] (1) William Rider, 1653–1665 (12 years); (2) Benjamin Keach, 1668–1704 (36 years); (3) Benjamin Stinton, 1704–1718 (14 years); (4) Dr. John Gill, 1720–1771 (51 years); (5) Dr. John Rippon, 1773–1836 (63 years); (6) Joseph Angus, 1837–1839 (2 years); (7) James Smith, 1841–1850 (8 ½ years); (8) William Walters, 1851–1853 (2 years); (9) Charles Spurgeon, 1854–1892 (38 years); (10) Arthur Tappan Pierson, 1891–1893 (Pulpit Supply Only, not installed as a Pastor – 2 years); (11) Thomas Spurgeon, 1893–1908 (15 years); (12) Archibald G. Brown, 1908–1911 (3 years); (13) Dr. Amzi Clarence Dixon, 1911–1919 (8 years); (14) Harry Tydeman Chilvers, 1919–1935 (15 ½ years); (15) Dr. W Graham Scroggie, 1938–1943 (5 years); (16) W G Channon, 1944–1949 (5 years); (17) Gerald B Griffiths, 1951–1954 (3 years); (18) Eric W Hayden, 1956–1962 (6 years); (19) Dennis Pascoe, 1963–1969 (6 years); (20) Dr. Peter Masters, 1970–present.

[19] It is naive to deny the Presbyterian influence on the subject of plural eldership. The Oxford English Dictionary credits John Calvin with first implementing a plural eldership at Geneva in the year 1541. In Calvin’s sermons on 1 Timothy (1579), he remarks on chapter 5, verse 17: “St. Paul setteth down two kind of governors of the church. He setteth down them that travail in the word, and them that are…to watch over…the people…that God to have his church well governed, would have Ministers to preach his word, and to be Shepherds: and besides them, men withal to govern, and that such should be chosen, which were of a good and holy life, that had already got some authority, and had also wisdom meet for such a charge.”

[20] John Gill, “An Exposition of the Old and New Testaments” (1746-63).

[21] In Gill’s “Practical Body of Divinity”, Pages 248-283, this matter of elder plurality is left open ended. Although he does not insist that a single church should have more than one pastor, his language is ambiguous and therefore must be weighed against the practice he adopted during his 51 years of ministry—Charles Spurgeon writes of Gill, in “The Metropolitan Tabernacle: Its History and Work”, 1876, pp 46,47: “In the Doctor’s later years the congregations were sparse and the membership seriously declined. He was himself only able to preach once on the Sabbath, and living in a rural retreat in Camberwell, he could do but little in the way of overseeing the church. It was thought desirable that some younger minister should be found to act as co-pastor. To this the Doctor gave a very decided answer in the negative, asserting “that Christ gives pastors is certain, but that he gives co-pastors is not so certain.” He even went the length of comparing a church with a co-pastor to a woman who should marry another man while her first husband lived, and call him a co-husband.”

[22] C. H. Spurgeon’s Autobiography, Vol 3, Pages 22-38.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] C. H. Spurgeon’s Autobiography, Vol 2, Page 357.

[26] A. G. Randalls, “Today’s Gospel and Apostolic Exhortations”, 1997, Pages 22-24. “Though C. H. Spurgeon professed to hold the doctrine of Particular Redemption he constantly contradicted the distinct work of the Holy Spirit in his ministry with expressions that denied the Trinitarian scheme of salvation. He imbibed Andrew Fuller’s error that saving faith is a moral duty binding upon the elect and the non-elect alike…”

[27] I have examined Spurgeon’s personal ‘communion kit’ which he is reported to have shared with guests in the privacy of his house. Although many Reformed Baptists would not be this ‘open’ with the Table, Baptist historian Kenneth Dix points out that “restricted communion is now less rigidly observed than it once was.”, “A Sketch of Baptist History”.

[28] Is this not what Spurgeon himself confessed in his “Autobiography”, pages 22-38? He was a young man, thrown into the position of managing a mega-church, requiring more of his energies than he had to share—so he complains, “we have a preaching elder,—that is, the Pastor,—and he is expected to perform all the duties of the eldership.” A plural ‘eldership’, therefore, was an attractive means of relieving him from his massive pastoral duties.

[29] The label “Reformed Baptist” appears to have been adopted by a hybrid of Baptist/Presbyterian brethren in the 1960’s. (See Clifford Pond, Only Servants, page 14) However, it is questionable whether Spurgeon himself would have accepted the label, for he clearly distinguishes the Reformers from the Baptists in his book, “The Metropolitan Tabernacle: Its History and Work, 1876, p 14: “The fortunes of war brought a Presbyterian parliament into power, but this was very little more favorable to religious liberty than the dominancy of the Episcopalians; at least the Baptists did not find it so. Mr. Edwards, a precious brother of the stern “true blue” school, told the magistrates that “they should execute some exemplary punishment upon some of the most notorious sectaries,” and he charges the wicked Baptists with “dipping of persons in the cold water in winter, whereby persons fall sick.”…Moved by the feeling that it was the duty of the state to keep men’s consciences in proper order, the Parliament set to work to curb the wicked sectaries, and Dr. Stoughton tells us: — ‘By the Parliamentary ordinance of April, 1645, forbidding any person to preach who was not an ordained minister, in the Presbyterian, or some other reformed church — all Baptist ministers became exposed to molestation, they being accounted a sect, and not a church. A few months after the date of this law,, the Baptists being pledged to a public controversy in London with Edmund Calamy, the Lord Mayor interfered to prevent the disputation — a circumstance which seems to show that, on the one hand, the Baptists were becoming a formidable body in London, and, on the other hand, that their fellow-citizens were highly exasperated against them.’”

[30] Apart from the eldership issue, A. G. Randalls argues that Dr. Masters, like Spurgeon before him, embraces the philosophy of Fullerism, which is a hallmark of the Reformed Baptist movement. “Today’s Gospel and Apostolic Exhortations”, 1997, Pages 27,28.

[31] John Gill is not the first or last Baptist pastor/theologian to advance the view that the terms bishop, pastor and elder are interchangeable, therefore identifying the same group of officers. However, as he stands as one of the earliest Baptist theologians, and his writings continue to influence succeeding generations, he may well be used to represent this point of view.

[32] John Gill, Practical Body of Divinity, page 250: “These pastors and teachers are the same with “bishops,” or overseers, whose business it is to feed the flock, they have the episcopacy or oversight of, which is the work pastors are to do; which office of a bishop is a good work; and is the only office in the church distinct from that of deacon,(1 Tim. 3:1, 8; Phil. 1:1). And these bishops are the same with “elders;” when the apostle Paul had called together at Miletus the elders of the church at Ephesus, he addressed them as “overseers,” επισκοπους, “bishops,” (Acts 20:17, 28) and when he says, he left Titus in Crete, to ordain elders in every city, he proceeds to give the qualifications of an elder, under the name of a bishop; “A bishop must be blameless,” &c. plainly suggesting, that an elder and a bishop are the same (Titus 1:5-7) and the apostle Peter exhorts the “elders,” to “feed the flock of God, taking the oversight,” επισκοπης, acting the part of a bishop, or performing the office of one (1 Peter 5:1, 2).”

[33] Clifford Pond, Only Servants, Page 35.

[34] The Strict Baptists are only one of many historic groupings of churches under attack by the Reformed Baptist Movement. Robert Wring, in his ‘Dissertation Submitted to the Doctor of Philosophy Committee of the Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary’, 2002, argues this case with reference to the Southern Baptist churches in the United States.

[35] Robert Wring coined this term to identify the amalgamation of Presbyterian and Congregational systems of church polity.

[36] A legitimate question is whether this movement should be identified as Reformed Baptist, or Reformed Presbyterian; for as one Reformed Baptist remarked, ‘if it were not for paedobaptism, I would be a Presbyterian’—as if the subject of baptism alone distinguishes a Baptist from a Presbyterian.

[37] In his audio lectures on the New Testament church, Dr. Richard Clearwaters states, with reference to more than one central leader overseeing a single fellowship, “that any body with more than one head is a monster”.

[38] Clifford Pond, Only Servants, Page 32.

©2013 Jared Smith. All Rights Reserved.

Jared Smith served twenty years as pastor of a Strict and Particular Baptist church in Kensington (London, England). He now serves as an Evangelist in the Philippines, preaching the gospel, organizing churches and training gospel preachers.

Jared Smith's Online Worship Services

Jared Smith's Sermons

Jared Smith on the Gospel Message

Jared Smith on the Biblical Covenants

Jared Smith on the Gospel Law

Jared Smith on Bible Doctrine

Jared Smith on Bible Reading

Jared Smith's Hymn Studies

Jared Smith on Eldership

Jared Smith's Studies In Genesis

Jared Smith's Studies in Romans

Jared Smith on Various Issues

Jared Smith, Covenant Baptist Church, Philippines

Jared Smith's Maternal Ancestry (Complete)